The 2024 Republican Party Platform endorses universal “baseline” taxes on all imported goods.[1] This plank reflects former President Donald Trump’s proposal for an across-the-board 10 percent tax on imports[2] and former U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer's call for ever-increasing tariffs unless the trade deficit is eliminated.[3]

These broad-based tariff proposals are a costly reaction to the economically questionable fear that trade deficits are making us poorer.

Trade deficits do not make us poorer

According to the Center for Renewing America (CRA), which has endorsed a universal basic tariff on imports: “When the U.S. runs a trade deficit, as it has for decades, it buys foreign goods with debt or with profits from the sale of American assets, exchanging trillions of dollars of long-term wealth for short-term consumption.”[4] Along the same lines, in his book No Trade Is Free, Ambassador Lighthizer writes: “Huge persistent trade deficits are making the United States poorer.”[5]

Those statements are incorrect.

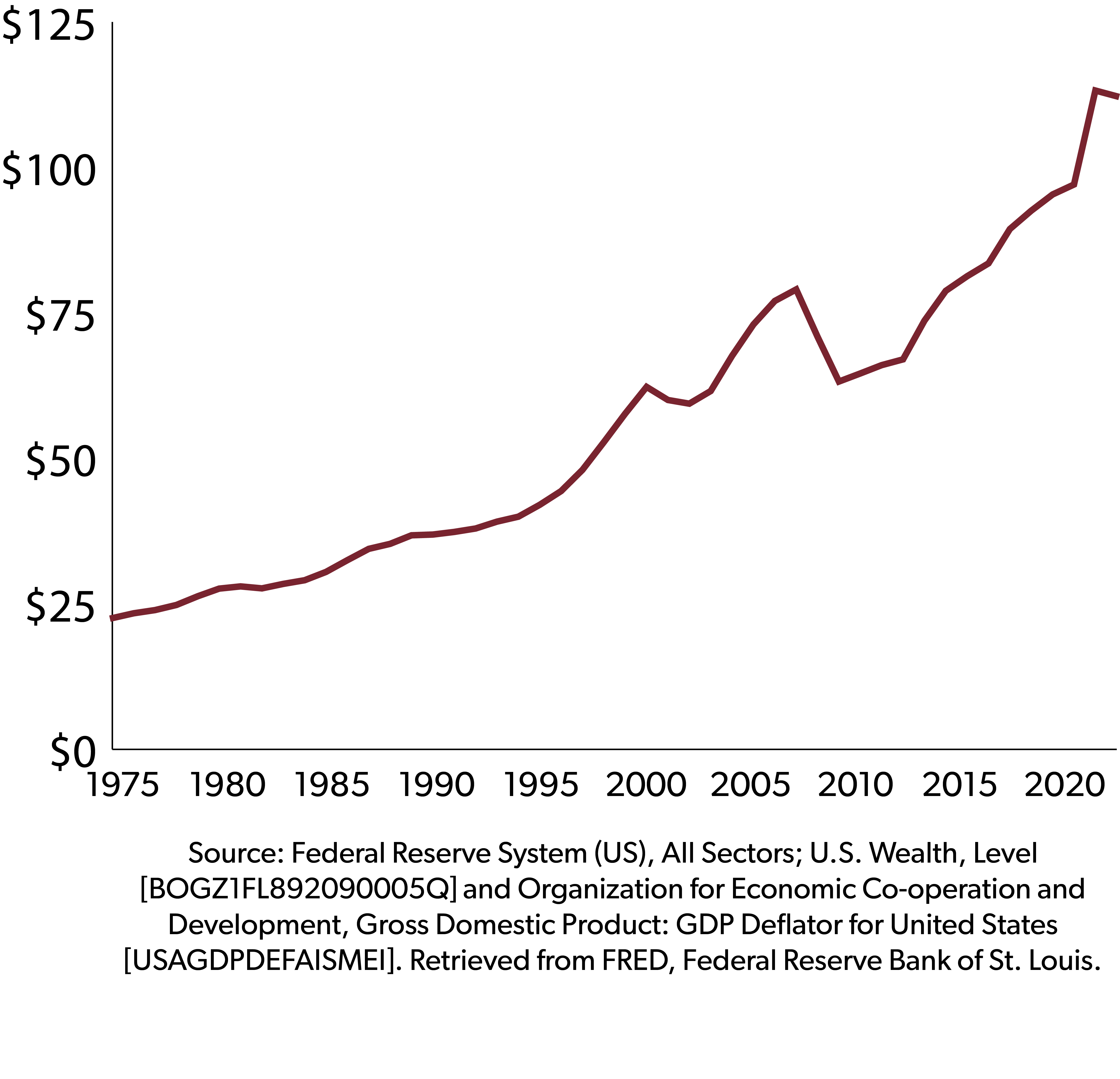

The United States has run trade deficits for 48 years in a row. During that time frame, real U.S. national wealth quintupled. We got richer, not poorer.[6]

Trade deficits reflect the desire of our trading partners to invest in America, providing dollars that fuel economic growth. When we import goods from abroad, those dollars are used to purchase U.S. goods and services or to invest in the U.S. economy. Whether our trading partners buy Nebraska-grown corn or invest in California-based Apple, Americans benefit.

Figure 1: Have 48 Years Of Trade Deficits Made Us Poorer? (Real U.S. Wealth, Trillions Of 2015 Dollars)

Protectionists misunderstand the relationship between budget deficits and trade deficits

The assertion by many protectionists that trade deficits cause the country to go into debt is backwards. Federal borrowing contributes to the trade deficit, not the other way around.

If someone buys a carton of strawberries grown in Mexico, that adds to the U.S. trade deficit, but it doesn’t mean they are in debt to Mexico. Protectionists add to the confusion by suggesting that when one shopper buys produce grown in Mexico, the rest of us somehow owe Mexico money because the trade deficit increases.

Here’s how things really work. Our trading partners use many of the dollars they earn from exports to purchase Treasury securities issued by the federal government to finance its massive budget deficits. Obviously, these purchases do not cause the federal government to go into debt; they just finance the debt created by federal deficit spending.

This may add to the trade deficit by reducing the supply of dollars available to buy U.S. exports. For example, last year, the federal government sold $614 billion in Treasury securities to foreign investors and governments. That’s $614 billion that could otherwise have been spent on U.S. exports.

The causal relationship is that budget deficits contribute to increased trade deficits, not the other way around. The solution is for the federal government to reduce budget deficits, not massively increase import taxes.

However, as long as the government keeps running big budget deficits, Brookings Institution economist Donald Kohn points out that foreign purchases of Treasury securities puts downward pressure on interest rates.[7] This benefits everyone from first-time homebuyers to manufacturers seeking financing to expand their operations.

Imports do not subtract from manufacturing output

Protectionists repeatedly allege that imports displace domestic production. CRA references the need to restore or buttress “shrinking” manufacturing industries threatened by imports. Amb. Lighthizer alleges that U.S. manufacturing has been “hollowed out.” The GOP platform promises to “restore” American manufacturing.

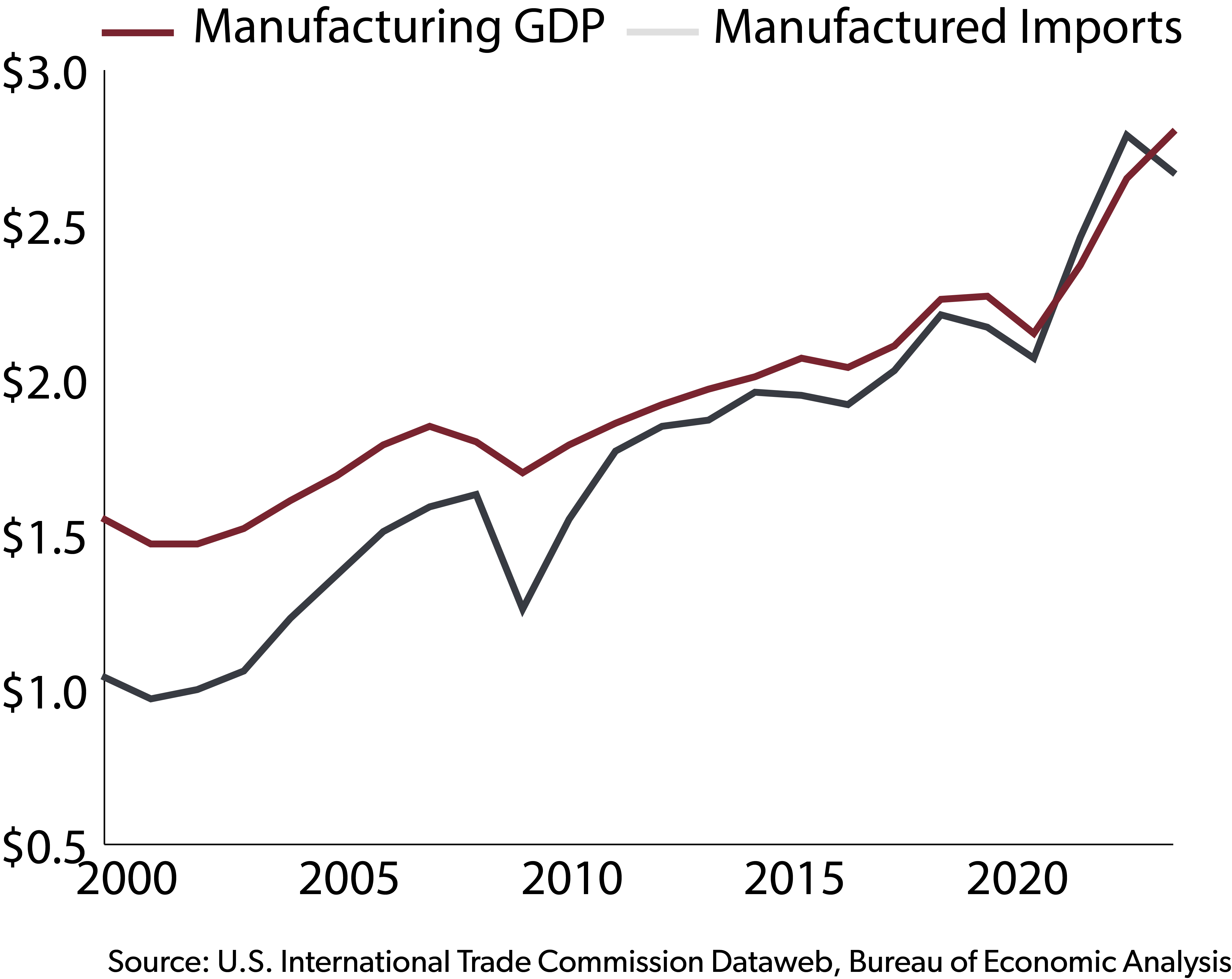

Increased imports of manufactured goods have not reduced U.S. manufacturing output.

During the last 10 years, every dollar of increased manufactured-goods imports corresponded to nearly a dollar of increased U.S. manufacturing output.[8] Despite economic disruptions created by the pandemic and the imposition of tariffs on goods needed by U.S. manufacturers, real manufacturing output hit an all-time high in 2023.[9] American manufacturing employment in 2023 was the highest in 15 years, just before the start of the Great Recession.[10]

Figure 2: Imports Of Manufactured Goods Do Not Reduce U.S. Manufacturing Output

Universal tariffs would make us poorer

A new, broad-based tariff wouldn’t eliminate the trade deficit, which is driven by the desire of our trading partners to invest in American stocks, bonds, real estate, and factories. New tariffs wouldn’t change that inclination. What they would do is inflict significant costs on Americans.

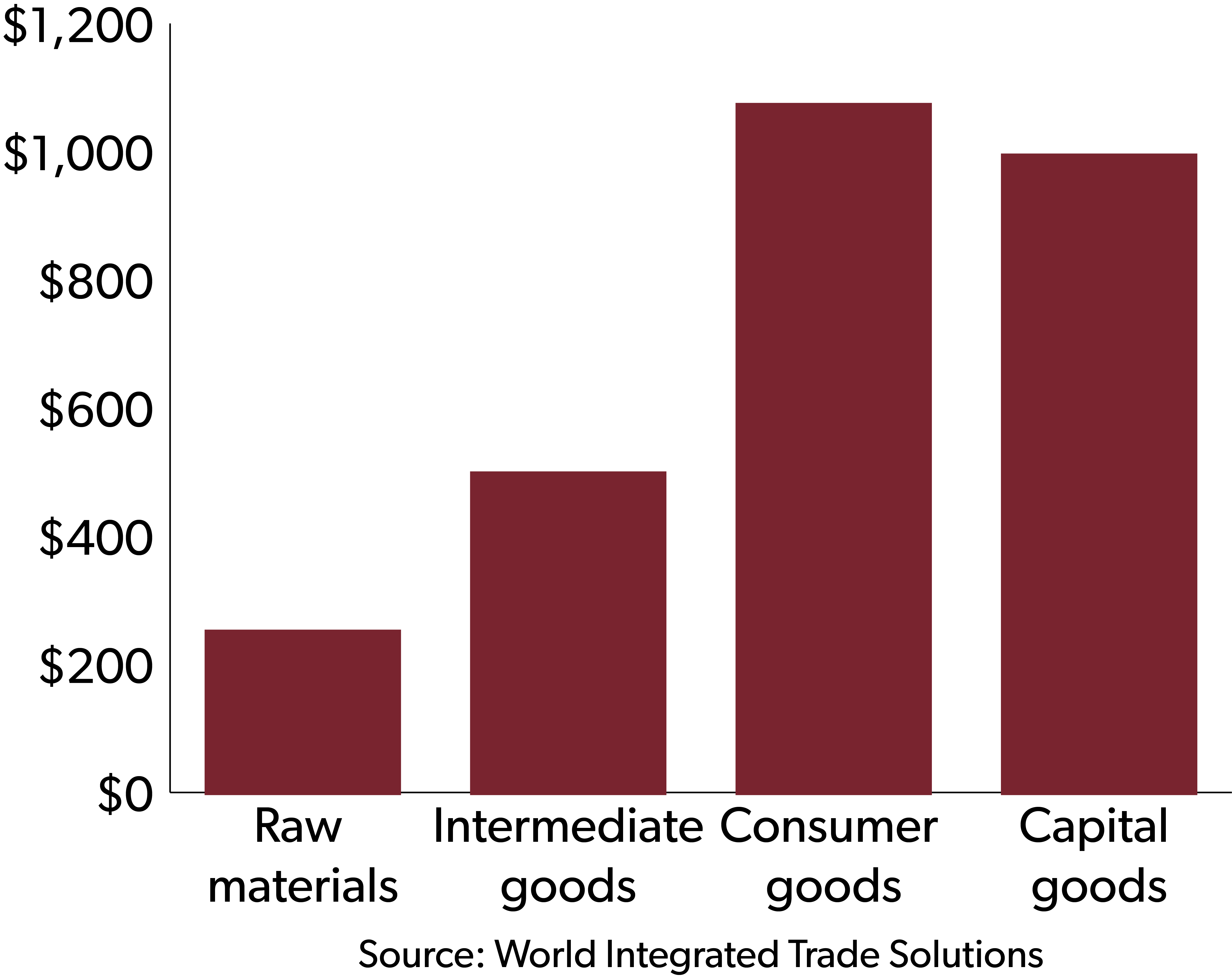

Since greater than 60 percent of U.S. imports are either capital goods, intermediate goods, or raw materials, new tariffs would damage U.S. producers who rely on those goods.[11]

Figure 3: 2021 U.S. Imports By Category (Billions)

The Peterson Institute for International Economics calculates that a 10 percent global tariff would cost an average of $300 billion a year over the next 10 years, the equivalent of $2,282 per household.[12]

A new universal baseline tariff would also reduce the ability of our trading partners to afford U.S. exports and to invest in our economy. The inevitable foreign retaliation against American exporters would exacerbate the damage.

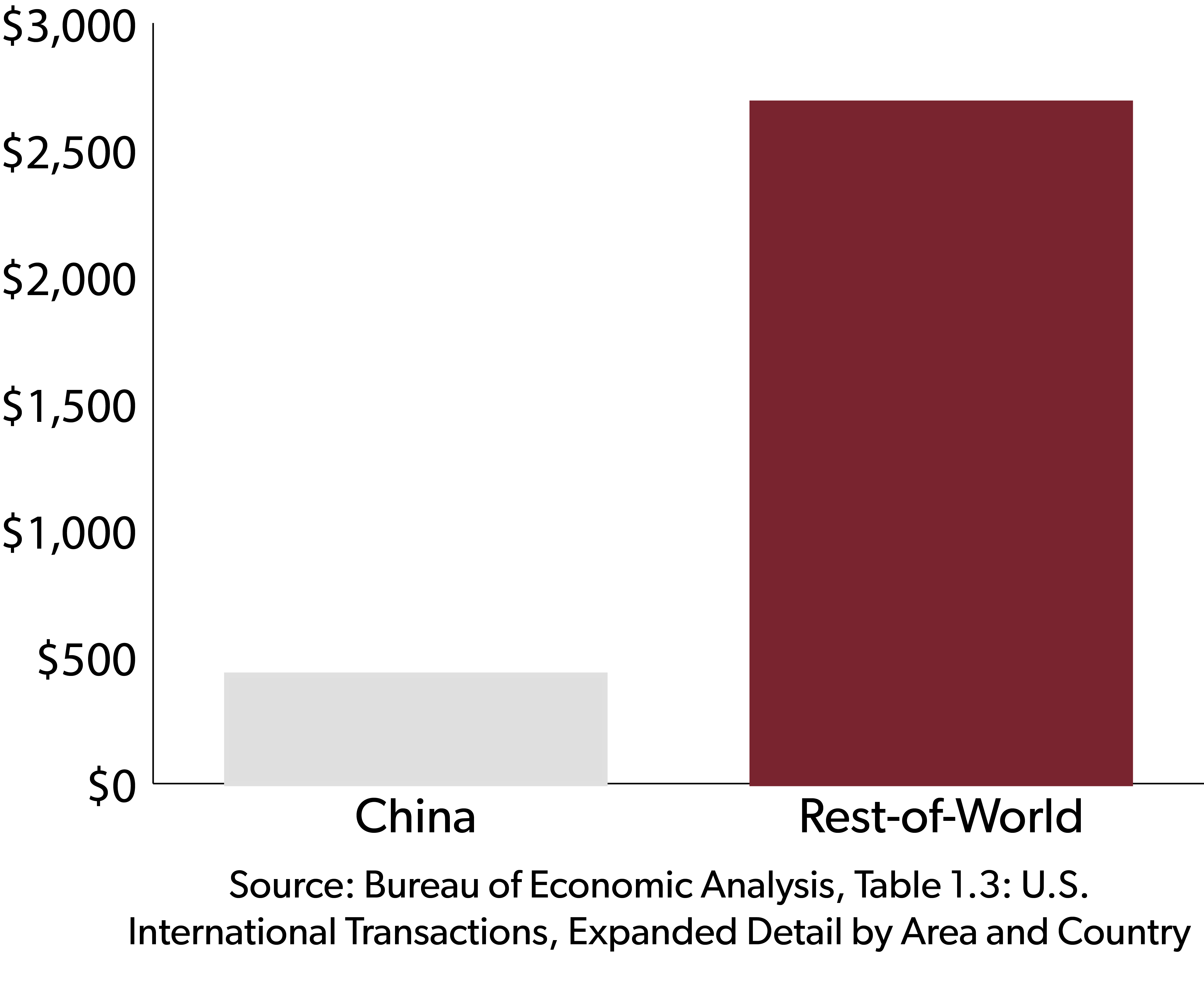

A universal tariff would mainly hit imports from countries other than China

Worldwide, 86 percent of U.S. goods imports come from countries other than China.[13] Americans import twice as much from Canada and Mexico as we do from China and over 60 percent more from the European Union, Great Britain, and Switzerland than from China.

Targeting these countries, along with other significant suppliers like Japan and Korea, with a universal tariff would primarily hit imports from current and prospective U.S. friends and allies.

Figure 4: A Universal Basic Tariff Would Mostly Hit Imports From Countries Other Than China

The Pew Foundation reports that these countries have a much more favorable view of the United States than they do of China.[14] Alienating them would be counterproductive to U.S. economic and security interests. Strengthening economic ties with our allies is one of the contributing factors that helped us win the Cold War.

Instead of imposing big tax increases on American families and businesses based on the economically misguided belief that trade deficits make us poorer, policymakers should embrace pro-taxpayer reforms designed to spur economic growth and pursue a trade policy that strengthens our ability to work with U.S. allies to counter China.

[1] 2024 Republican Party Platform | The American Presidency Project. (n.d.). https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/2024-republican-party-platform.

[2] Smith, E. (2024). “Trump’s proposed 10% tariff plan would “shake up every asset class,” strategist says. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2024/01/22/trumps-proposed-10percent-tariff-plan-would-shake-up-every-asset-class-strategist.html.

[3] The Economist. (2021). “Robert Lighthizer on the need for tariffs to reduce America’s trade deficit,” The Economist. https://www.economist.com/by-invitation/2021/10/05/robert-lighthizer-on-the-need-for-tariffs-to-reduce-americas-trade-deficit.

[4] (2024). One Pager: What is a Tariff For? The Center for Renewing America. https://americarenewing.com/issues/one-pager-what-is-a-tariff-for/.

[5] Lighthizer, R. (2023). No Trade Is Free: Changing Course, Taking on China, and Helping America's Workers. HarperCollins, Page 29.

[6] All sectors; U.S. wealth, level. (2024). https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BOGZ1FL892090005Q, and National Accounts: National Accounts Deflators: Gross domestic product: GDP deflator for United States. (2024). https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USAGDPDEFQISMEI.

[7] Sutton, S. (2024). “What Trump’s tariffs would mean for the Fed,” Politico. https://www.politico.com/newsletters/morning-money/2024/06/26/what-trumps-tariffs-would-mean-for-the-fed-00164967.

[8] U.S. International Trade Commission. Imports for Consumption: NAICS 31, 32, and 33. https://dataweb.usitc.gov/. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Value Added by Industry: Manufacturing. https://www.bea.gov/itable/gdp-by-industry.

[9] Bureau of Economic Analysis. Real Value Added by Industry: Manufacturing. https://www.bea.gov/itable/gdp-by-industry.

[10] All employees, manufacturing. (2024). https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MANEMP.

[11] United States Trade Summary | WITS Data. (n.d.). https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/USA/Year/LTST/Summary.

[12] Klausing, K., and Lovely, M.E. (2024). Why Trump's tariff proposals would harm working Americans. Peterson Institute for International Economics. https://www.piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/2024/why-trumps-tariff-proposals-would-harm-working-americans.

[13] Bureau of Economic Analysis. Table 1.3. U.S. International Transactions, Expanded Detail by Area and Country. https://www.bea.gov/itable/international-transactions-services-and-investment-position.

[14] Silver, L. (2024). More people view the U.S. positively than China across 35 surveyed countries, Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/07/09/more-people-view-the-us-positively-than-china-across-35-surveyed-countries/.