Introduction

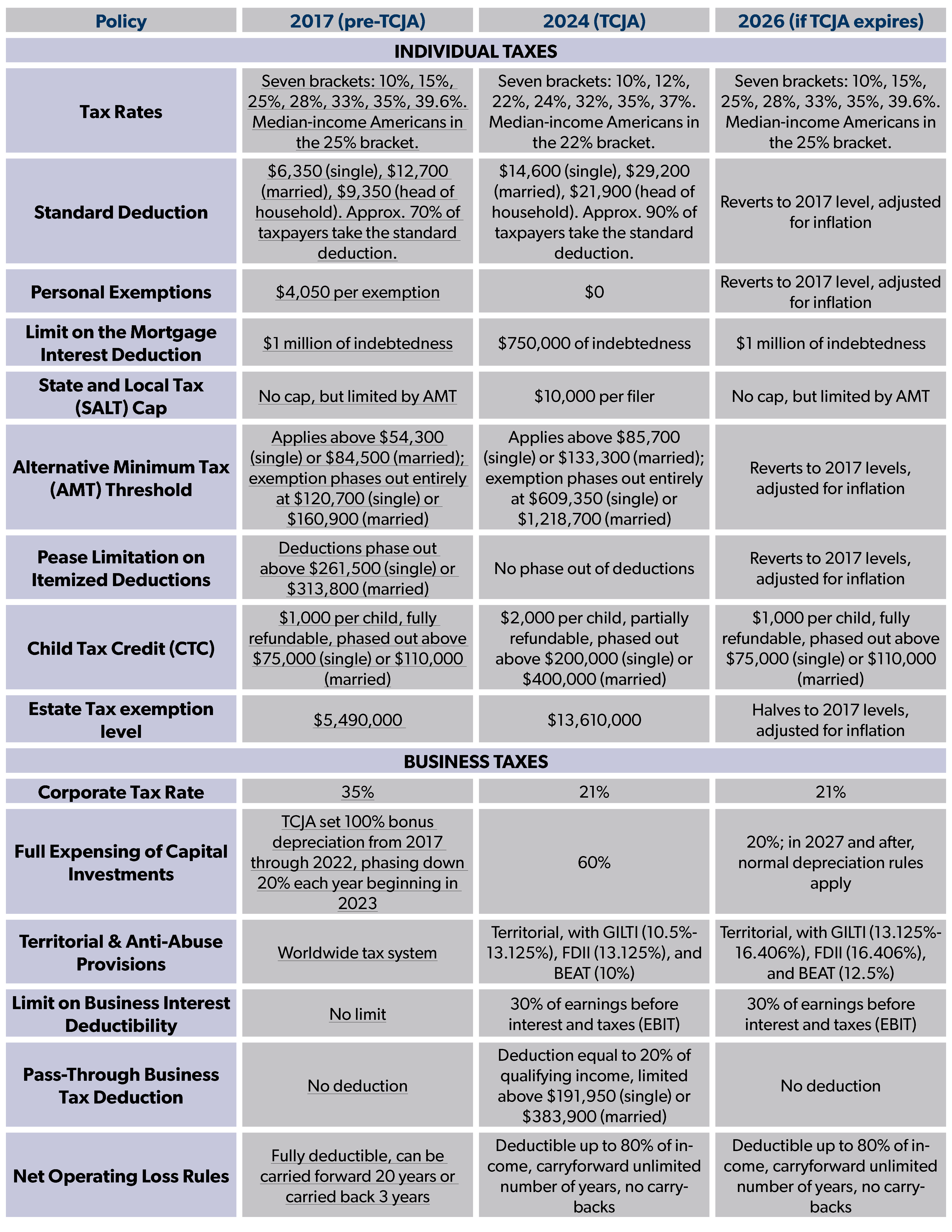

Several major fiscal issues will confront the new Congress in 2025: expiration of enforceable fiscal caps from the Fiscal Responsibility Act in July, a debt ceiling expiration sometime during the year, and expiration of much of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 on December 31. This report summarizes the expiring provisions of the TCJA, other tax policies that may be relevant in the 2025 debate, and current research as to policy options for Congress.

What is the TCJA?

The TCJA was signed into law by President Donald Trump on December 22, 2017, after several months of congressional debate, but the major themes of the bill had been discussed for years. Key elements included:

- Ending duplicative taxation of U.S. businesses operating overseas (and the resulting inversions, U.S. corporations reorganizing as a foreign corporate to enjoy territorial taxation) by moving from a worldwide tax scope to a territorial one and adopting anti-abuse provisions;

- A significant reduction in the corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent to improve the competitiveness of the U.S. tax rate compared to other countries;

- Full expensing, or allowing businesses to deduct the full cost of investments in the year made, instead of requiring deductions to be spread out over subsequent years (depreciation);

- Simplification and reduction of individual tax burdens, through across-the-board lower individual tax rates, a doubled standard deduction, an expanded child tax credit, patching the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), a doubled estate tax exemption level, and limitations on other exemptions and deductions; and

- Tax relief for pass-through businesses, or Section 199A, for non-corporate businesses.

One way of thinking of the TCJA is that it combined a roughly revenue-neutral business tax reform with an individual tax cut. Generally, the corporate provisions are permanent (except for full expensing and rate levels for the anti-abuse provisions), while the individual provisions expire at the end of 2025. This was to prevent a deficit impact outside the 10-year window, necessitated to comply with Senate reconciliation rules to avoid a threatened filibuster.

What is the Impact of the TCJA and a TCJA Extension?

With revenue decreases of $5.5 trillion over the 2018–27 period and revenue increases of $4 trillion, the TCJA was designed as a net tax cut of $1.5 trillion over 10 years. The Tax Foundation estimated that this would fall to $448 billion after accounting for economic impacts, finding positive impacts in particular from full expensing and the corporate income tax rate reduction. As Adam Michel of the Cato Institute recently summarized:

Kyle Pomerleau and Donald Schneider find that in the years immediately after 2017, “real GDP, consumption, business investment, and payrolls grew more rapidly than expected” by pre-reform forecasts from the Congressional Budget Office (Figure 3). Gabriel Chodorow-Reich and coauthors use variation in how firms were impacted by the tax cuts to estimate the TCJA will result in a long-run increase to the capital stock of 7.2 percent, roughly 50 percent larger than some of the most optimistic projections. This result implies a positive overall economic impact larger than the consensus range.[…]

Compared to the pre-TCJA wage trend, the average production and nonsupervisory worker received about $1,400 more in above-trend annualized earnings as of April 2020 (before the pandemic disruptions).

An extended TCJA would reduce federal revenue by more in its second decade than its first, due to several factors, such as economic growth since 2017, higher inflation and interest rates since 2020, and the mostly permanent nature of the corporate tax provisions. An extension of the TCJA post-2025 with no changes would reduce federal revenues by almost $4 trillion over 10 years. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the five extension provisions with the biggest revenue impact are lower individual income tax rates ($2.2 trillion), the AMT patch ($1.4 trillion), the doubled standard deduction ($1.3 trillion), the expanded child tax credit ($0.7 trillion), and the Section 199A pass-through deduction ($0.7 trillion). Other provisions and interest costs associated with higher national debt payments total $1.8 trillion. Extending repeal of personal exemptions and limits on itemized deductions together offset these by $2.9 trillion.

With the national debt now past $35 trillion, the debate over the TCJA extension presents an opportunity to discuss serious fiscal reforms, as well as putting the U.S. tax code on a permanent and sustainable course. The TCJA did significantly reduce tax compliance burdens for U.S. taxpayers—the burden fell from over 8 billion hours in 2017 to 6 billion hours in 2020, a time savings worth over $50 billion. Further simplification and reforms could cut this cost further. This report reviews policy options that policymakers face on expiring and related provisions, as well as administrative and IRS efficiency ideas for action from our Taxpayers FIRST advisory panel. NTUF’s Taxpayers’ Budget Office also regularly makes recommendations for reforming Congressional Budget Office (CBO) scoring practices to deter gimmicks that conceal the true cost of congressional proposals.

How did the TCJA change individual taxes?

Individual Tax Rate Reductions. The TCJA cut individual tax rates across the board, with most tax brackets seeing a reduced rate and the top rate dropping from 39.6 percent to 37 percent. These reductions will expire at the end of 2025, and the higher rates will then return unless Congress acts.

All told, about 80 percent of Americans received a tax cut under the TCJA, with an average tax savings of over $2,100. Only about 5 percent of Americans received a tax increase as a result of the law. While it is true that just a little over half of the lowest quintile of income earners received a tax cut, this is because a lot of Americans in that income group owe zero federal income taxes. Just 1.2 percent of lowest-quintile Americans saw a tax hike.

As a result of the TCJA, the share of the federal income tax burden paid by the top 10 percent of income earners rose from 70.1 percent pre-TCJA to 71.3 percent post-TCJA. It’s also not because they earned more income—this same income group’s share of total adjusted gross income (AGI) actually dipped slightly from 47.74 percent to 47.66 percent. Meanwhile, the bottom 50 percent of income earners’ share of total AGI increased from 11.25 percent pre-TCJA to 11.61 percent post-TCJA. At the same time, that group’s share of federal income taxes dropped from 3.11 percent to 2.94 percent. NTUF produces annual analysis on Who Pays Income Taxes & Who Doesn’t Pay Income Taxes.

Historically, while U.S. income tax rates have varied widely (once reaching 91 percent in the 1950s until the Kennedy/Johnson tax cut of 1964), income tax revenue as a percentage of the economy has remained relatively stable. In other words, high tax rates haven’t raised more tax money, because higher rates increase demand for and value of exemptions, deductions, and income-avoidance strategies. In 1961, the income tax rates between 52 percent and 91 percent raised just 0.11 percent of GDP in revenue.

The U.S. is also higher than the international average on income taxes, but lower on payroll and consumption taxes. A worker earning $40,000 would pay $11,648 in U.S. federal taxes (mainly income and payroll taxes) but $17,533 in total taxes in the rest of the developed world.

43 states and DC also impose their own state income taxes, and some local governments impose income taxes as well. 29 states and DC have graduated-rate income taxes, while 12 states have one flat rate applying to all income in the state. One state (Washington) taxes only capital gains income and one state (New Hampshire) taxes only dividend income. In recent years, there has been a trend of numerous states moving to single-rate income taxes or reduced income tax burdens.

President Biden has included budget proposals that would allow the TCJA individual income tax cuts to expire for single filers making more than $400,000 a year and married couples making more than $450,000 a year, impose a new 25 percent minimum tax on those with wealth over $100 million, and taxing capital gains as ordinary income for households making over $1 million. Other proposals for income tax changes have included raising the top rate to 49 percent or higher, eliminating the current income cap on Social Security payroll taxes, moving to a flatter or flat tax, or greatly reducing income tax carveouts and reducing the rate. Some have also proposed a wealth tax or tax on unrealized gains.

Expanded Standard Deduction. A key goal of the TCJA was to simplify the tax code and reduce compliance costs. One way in which the TCJA’s authors aimed to accomplish this was by nearly doubling the standard deduction, in 2018 from $6,500 to $12,000 for single filers and from $13,000 to $24,000 for married filers, thereby expanding the number of taxpayers who take the set standard deduction rather than itemizing separate deductions. The expanded standard deduction also replaced personal and dependent exemptions.

In 2024, 150.3 million taxpayers (90.1%) take the standard deduction while 16.4 million taxpayer itemize; prior to the TCJA, 46.5 million taxpayers (30%) itemized. Our estimate that a projected fall in itemizers from 30% to 8%—which has nearly come to pass—means the expanded standard deduction saves Americans 210 million hours a year in compliance costs worth $13 billion.

Notably, of six post-2025 tax plans prepared by outside organizations across the political spectrum, none would let the standard deduction revert to pre-2017 levels. 4 fully extend the expanded standard deduction, 1 expands it even further, and 1 partly extends it. The Clausing-Sarin (Hamilton Project) retains the expanded standard deduction, writing "On net, we view the higher standard deduction as a useful policy that simplifies tax paying for a group of people that no longer itemize." The Progressive Policy Institute retains the expanded standard deduction, writing "PPI would make the expansion permanent to cut taxes for lower- and middle-income Americans and reduce the impact that distortionary tax preferences have on our economy." The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget retains the expanded standard deduction. The Cato Institute retains the expanded standard deduction, saying it is "a de minimis exemption to all taxpayers so that some income is exempt from federal tax." The Tax Foundation proposes further expanding the standard deduction, comparing it to "a large zero bracket shielding low-income households from the...tax." Only the American Enterprise Institute would scale back the expanded standard deduction by 5% but not let it revert to pre-2017 levels, but note that "[t]he TCJA also improved simplicity for roughly 28 million taxpayers by raising the standard deduction, making them less likely to need to track and report itemized deductions."

Nine states and DC have adopted the federal standard deduction as theirs for state income tax purposes: Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Maine, Missouri, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Carolina, and the District of Columbia. Expiration of the federal expanded standard deduction would also mean a tax increase for taxpayers in those 9 states.

Limit on the Mortgage Interest Deduction (MID). The TCJA adjusted many itemized deductions, as well. The mortgage interest deduction (MID), which allows taxpayers who itemize their deductions to deduct mortgage interest payments on their first or second residences, was reduced from a maximum deductible amount of $1 million to $750,000. This reduction is set to expire at the end of 2025.

Advocates of the MID claim that it helps make homeownership more affordable for middle-class families. But even the vast majority of middle-class families do not benefit from the MID—in large part because only taxpayers who itemize their deductions can claim it. What’s more, among itemizing taxpayers who did claim the MID, over 60 percent of the benefit goes to taxpayers with adjusted gross incomes above $200,000.

But while the MID tends not to primarily benefit taxpayers that its advocates intend to target, arguably the greater drawback to the MID is its impact on homeownership. Rather than making homeownership more affordable, the MID tends to increase the cost of housing by driving up demand. So rather than helping middle-class taxpayers afford their mortgages, the MID tends to make housing more expensive, while at the same time benefiting those wealthier, itemizing taxpayers who are least likely to need the help.

State and Local Tax (SALT) Deduction Cap. The TCJA’s SALT cap allows taxpayers who itemize their deductions to deduct up to $10,000 of state and local income, sales, and property taxes paid. Taxpayers must choose whether to deduct either income or sales taxes under the SALT deduction, though they can deduct property and personal property taxes regardless. Prior to the passage of the TCJA, taxpayers could deduct an unlimited amount of state and local taxes. This $10,000 cap is set to expire at the end of 2025.

While detractors of this change have argued that it negatively affects the middle class, even before the cap, 84 percent of the benefit of the SALT deduction went to taxpayers making over $100,000 a year. An analysis by the Tax Policy Center found that repeal of the SALT cap would provide no benefit at all to 96 percent of middle-income taxpayers. Taxpayers making over $1 million, however, would receive an average tax cut of $48,000.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that the change to the SALT cap did not occur in a vacuum. Middle-income taxpayers who had their SALT deduction capped generally still had their tax obligations reduced on net due to the increased standard deduction, reduced individual income tax rates, and increased Alternative Minimum Tax exemption.

Curiously for a deduction that primarily benefits the wealthiest taxpayers, some of the SALT deduction’s most vociferous advocates are on the left. This is largely because the SALT deduction enables wealthier taxpayers in high-tax states to use their high state and local tax payments to reduce their federal tax burden. The SALT deduction therefore acts as a kind of shield against the full brunt of the high state and local tax burdens. Without the SALT deduction, taxpayers have been fleeing the high-tax states represented by pro-SALT deduction members of Congress en masse.

Proposals to uncap or increase the SALT deduction cap would have a significant impact on federal revenue. The Penn-Wharton Budget Model estimates that uncapping the SALT deduction beginning in 2024 would reduce federal revenues by over $1.1 trillion over the next decade compared to a continuation of the $10,000 cap, while raising the cap to $100,000 (or $200,000 for married filers) would reduce revenues by $829 billion. Failure to extend the SALT cap would likely come at the cost of real tax relief for average taxpayers.

Charitable Contributions Deduction. The TCJA did not significantly change the charitable contribution deduction, although it was feared a reduction in the number of itemizing taxpayers would harm charitable giving. U.S. charitable giving did drop from $335 billion in 2017 to $312 billion in 2019, but has risen in subsequent years. The Philanthropy Roundtable recently studied why charitable giving has remained resilient since the TCJA, offering explanations including non-tax motivations for personal giving, strong income growth and a strong economy, and other tax policies that encourage wealth creation and retirement saving.

The TCJA did decrease the maximum amount of total income a taxpayer may deduct as charitable contributions from 60 percent to 50 percent, and this provision expires at the end of 2025. This reduction was temporarily suspended in 2020 when the limit was raised to 100 percent. Also in 2020 only, Congress authorized an “above-the-line” charitable contributions deduction of up to $300, which any taxpayer could take.

Charitable organizations also benefit from other favorable tax treatment, including exemption of service income, an income tax exemption on revenue, and a high estate tax exemption. Charitable donations also benefit taxpayers by providing services that might otherwise be provided by government.

Moving expenses. Prior to 2018, employees could deduct unreimbursed moving expenses from their adjusted gross income or exclude reimbursements for moving expenses from their income. The TCJA eliminated both of these provisions, with the exception of allowing active duty members of the Armed Forces to deduct moving expenses for changes in station. These changes are due to expire alongside many other TCJA provisions at the end of 2025. Analysis has shown that prior to the TCJA, deductions for moving expenses were only claimed on about one million tax returns annually, amounting to about one percent of all returns. JCT estimated at the time that these two changes combined would raise $6.8 billion in taxes from 2018 through 2025.

Pease. Taxpayers with higher incomes face a variety of surtaxes and limitations that effectively raise their tax rate. One is the so-called Pease limitation, which reduced the value of itemized deductions by an escalating percent above a certain income threshold. In 2016, the threshold was $259,400 for single filers and $311,300 for married taxpayers filing jointly. The Pease limitation was first created in 1990, but has been repealed or suspended several times since then. The TCJA suspended the Pease limitation through 2025. Pease adds unnecessary complexity to the tax code. Congress can limit itemized deductions for high-income taxpayers in simpler and more transparent ways, such as the TCJA’s cap on SALT deductions.

Capital gains. The TCJA did not change the tax rates for capital gains, but changes to taxation of both realized and unrealized gains are frequently proposed. Long-term capital gains are those held for at least one year and are taxed at 0 percent, 15 percent, and 20 percent depending on the taxpayers’ income bracket. Short-term capital gains are held for under one year and are taxed at the same rate as ordinary income. Despite no rate changes, the tax treatment of capital gains was affected by the TCJA, as it changed the tax brackets for ordinary income and thus short-term capital gains.

It is important to note that most assets subject to capital gains taxes also face other taxes throughout the tax code, resulting in double taxation. For example, the gain earned from dividends or stock appreciation first faces the corporate income tax before the benefit is passed to the taxpayer. Other flaws with the tax treatment of capital gains include that capital gains are not indexed for inflation., Even if the entire gain in the asset’s value is offset by inflation, the taxpayer would still owe tax on the gain. The tax code currently addresses the increase in an asset’s value over time through a step-up in basis, yet this could be done more efficiently by indexing capital gains to inflation. Legislators have also introduced legislation to index the amount of capital losses taxpayers can claim to inflation.

The Biden Administration has proposed taxing long-term capital gains as ordinary income, taxing carried interest as ordinary income rather than as a capital gain, and taxing unrealized gains. Each of these proposals have been dubbed as a way to increase fairness in the tax code, but would actually have the opposite effect. As mentioned above, since the assets subject to capital gains taxation are often already subject to other elements of the tax code, treating them as ordinary income would disincentivize long-term investment.

What some policymakers refer to as closing the carried interest loophole by treating it as ordinary income would discriminatorily raise taxes on investment. Carried interest generally refers to commission earned by partners of hedge funds or private equity funds based on the return in value of the fund. These commissions are appropriately taxed at the long-term capital gains tax rate due to their value hinging on investment risk. They are also typically held in the fund for several years. The TCJA required that carried interest be held for three years in order to be taxed at the long-term capital gains rate, rather than the typical one year requirement. Proposals to treat carried interest as ordinary income typically also require taxes to be paid in the year the commission is earned rather than when the gain is realized after the holding period.

Finally, the Biden Administration has also proposed taxing unrealized gains. Rather than waiting until the taxpayer realizes the gain through selling or otherwise disposing of the capital asset, this proposal would require taxes be paid even if the taxpayer is still holding the asset. This proposal strays far from conventional tax policy, as unrealized gains are not income. It also raises several concerns including how to appropriately treat capital losses and whether the tax can even be paid, as typically taxpayers would use a portion of the gain to pay their tax liability. While both calculating and administering the tax would be incredibly difficult, the Biden Administration believes their policy could raise $503 billion over ten years.

Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT). Dividends, certain capital gains from real estate transactions, and other passive business income sources are covered by the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT). This is a tax of 3.8 percent paid by taxpayers with modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) over $200,000 or $250,000 for joint filers. These income thresholds are not adjusted for inflation. The NIIT has been in place since 2013 and was not changed by the TCJA, but the Biden Administration has proposed raising the rate to 5 percent for individuals earning over $400,000. Other proposals have included expanding the scope of the NIIT, which many organizations believe would capture small businesses income that was not the intended target of the tax. Of note, while the NIIT is sometimes referred to as the “unearned income Medicare contribution,” the tax revenues do not in fact contribute to the Medicare trust funds.

Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) patch and repeal. All taxpayers have the ability to reduce their tax liability by claiming credits, deductions, and other tax incentives for which they are eligible. As more of these incentives are signed into law each year, some taxpayers may be eligible for significant tax reductions. In 1969, Congress enacted a minimum tax to prevent high-income taxpayers from reducing their tax liability to zero through credits and deductions. The alternative minimum tax (AMT) as we know it today was enacted in 1982 and is progressive with two rates, 26 percent and 28 percent. The AMT is a tax system that is parallel to the rest of the tax code, with taxpayers completing separate forms during tax filing to determine whether they are subject to it.

Prior to the TCJA, single taxpayers could exempt $54,300 from their income for AMT calculation, while married filers could exempt $84,500 and married couples filing separately could exempt $42,250. At higher incomes when the 28 percent rate kicks in, those amounts were $187,800 for single and married filers and $93,900 for married couples filing separately. Because these exemption levels affect millions of taxpayers, the AMT was routinely “patched” on an annual basis to limit its reach to only very high-income individuals. Nearly 5 million taxpayers had an additional tax liability under the AMT in 2017, and the tax has faced criticism from both the right and the left.

While a draft version of the 2017 tax reform eliminated the AMT entirely, the TCJA ultimately continued this patch and raised the amount of income that taxpayers could exempt from the calculation to $70,300 for single filers and $109,400 for married filers who file jointly. It also alleviated AMT’s marriage penalty and was structured to reduce the burden to the middle class. The TCJA’s AMT patch continues for the entire 2018 to 2025 period, but the exemption and phaseout threshold will revert to pre-TCJA levels at the end of 2025.

Personal Exemption Phaseout (PEP). Taxpayers have historically been able to reduce their taxable income by claiming a personal exemption for themselves, a spouse, and their dependents. The personal exemption is a fixed amount that is adjusted annually for inflation, and equaled $4,050 per person in 2017 prior to the TCJA taking effect. The TCJA made the personal exemption $0, effectively repealing it, until the end of 2025. The TCJA instead opted to allow taxpayers to reduce their taxable income by doubling the standard deduction and expanding child tax credits, resulting in a more efficient tax reduction.

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 introduced the personal exemption phaseout (PEP) for higher income taxpayers. The exemption phases out at a rate of 2 percent for every $2,500 in adjusted gross income (AGI) exceeding a threshold amount. These threshold amounts are adjusted annually for inflation and were $261,500 for single filers and $313,800 for married taxpayers filing jointly in 2017. The PEP was briefly repealed by the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 and only returned when the provision expired.

Child Tax Credit (CTC). The child tax credit (CTC) was originally created by a Republican Congress in 1997 and was expanded by the TCJA in an effort to reduce the tax burden for families. The TCJA doubled the CTC from $1,000 per child to $2,000, increased the income phase-out threshold from $75,000 for individuals and $150,000 for couples to $200,000 for individuals and $400,000 for couples, and reduced refundability of the credit from 100 percent to 80 percent. The TCJA also included a minimum earned income requirement for the CTC and required children to have a social security number to qualify for their parents to receive the CTC. In 2021, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) temporarily increased the CTC to $3,000 per child and $3,600 per child aged six and under. The CTC has since reverted back to the TCJA’s level of $2,000 per child, and will revert to permanent law of $1,000 per child once this provision expires at the end of 2025.

Despite its bipartisan appeal, the CTC is increasingly expensive for the federal government. Estimates suggest that extending the TCJA’s CTC after its expiration would have a fiscal impact of about $750 billion over ten years, whereas that of expanding ARPA’s CTC would be into the trillions. Yet the CTC benefits from lower administrative costs and greater efficiency than other government programs targeted towards low-income families, and it can have a significant impact on children living in poverty.

Several design options are available to Congress to maximize the impact of the CTC in a fiscally-responsible manner. NTUF has proposed a comprehensive set of CTC reforms which would include making permanent the $2,000 per child credit and adding a $400 bonus credit for children age five and under, beginning the income phase out for single filers at $75,000 per year and $150,000 for joint filers, indexing the refundable portion to inflation, and allowing parents to opt-in for quarterly payments. The Tax Reform for American Families and Workers (TRAFWA) Act also includes fiscally sound and effectively targeted CTC changes, such as preserving the $2,000 per child credit and indexing the credit to inflation. With TRAFWA currently at an impasse, Congress can consider its CTC changes alongside several other thoughtful designs that have been proposed in the lead up to 2025.

Education credits/student loan interest deduction. Higher education is incredibly subsidized in the U.S., while costs remain high, hurting the taxpayers who ultimately foot the bill. In an attempt to address the issue, President Biden has taken the costly and illegal step of canceling student loan debt while failing to address the underlying incentive structures that are driving up costs. Congress should address this issue in upcoming tax reform.

Early in the crafting of the TCJA, House Republicans drafted a plan to meaningfully tackle the cost of higher education for students and taxpayers, yet it was ultimately left out of the final bill. This plan would have consolidated three existing tax credits: the American Opportunity Credit, the Lifetime Learning Credit, and the Hope Scholarship Credit. It also would have eliminated the student loan interest deduction of up to $2,500, a move that has bipartisan support and was previously proposed by former President Obama. While the TCJA expanded 529 savings plans to cover K-12 expenses, efforts to include homeschool and vocational expenses were not included.

Health insurance premium credit. Health insurance premium tax credits will be on the table for tax reform discussions, as changes made by the Inflation Reduction Act expire at the end of 2025. The premium tax credit (PTC) was created by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) as a refundable credit for certain lower income households purchasing health insurance through an ACA health insurance exchange. The amount of the PTC varies for each individual and is calculated based on modified adjusted gross income (MAGI), the taxpayer’s health insurance premium, and other factors. The PTC is available to taxpayers earning income of at least 100 percent of the federal poverty level and begins to phase out for taxpayers earning 400 percent of the federal poverty level, yet the phase out was eliminated until 2026 by the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) and Inflation Reduction Act.

Estate tax. The federal government taxes inheritances and gifts above the exemption threshold at rates of up to 40 percent. Rates for each gradually increase after the exemption threshold is exceeded, reaching the maximum 40 percent tax rate on gifts and inheritances $1 million over the exemption threshold. Exemptions are adjusted annually for inflation, and are doubled for married filers. Estate tax thresholds apply to the gross value of the estate, while gift tax thresholds apply per recipient. Both gifts above the gift tax exemption threshold and the value of a transferred estate count toward a “unified credit” that is equivalent to the estate tax exemption—in other words, gifts above the gift tax threshold count towards the donor’s eventual estate tax exemption.

The TCJA doubled the exemption for the estate tax beginning in 2018, raising it from $5.49 million to $11.18 million that year. For 2024, the estate tax exemption is $13.61 million, while the annual gift tax exemption is $18,000 (both doubled for married individuals). The doubling of the estate tax exemption (and, consequently, the unified credit) is set to expire after 2025, at which point it will revert to the pre-TCJA level of $5.49 million, adjusted for inflation.

As well as acting as a tax on saving, the estate tax is one of the most burdensome and complicated taxes in the tax code. In 2017, before the passage of the TCJA, NTUF estimated that the 12,411 estate tax filers spent a combined 2,099,259 hours on estate tax compliance. Given a conservative estimate of hourly rates of around $300 per hour for probate lawyers (large estates can often be more expensive to settle, and some probate lawyers charge a percentage of the value of the estate), this works out to a compliance cost of roughly $630 million, or over $50,000 per filer.

The TCJA led to a sharp decline in the number of estates subject to the tax, with the number of taxable estates dropping from 5,185 in 2017 to 2,584 as of the last IRS data release in 2021. Due to economic growth and inflation, revenue from the estate tax has stayed relatively steady—dropping only from $19.9 billion in 2017 to $18.4 billion in 2021. The Tax Foundation has estimated that extending the doubled estate tax exemption through 2033 would reduce revenue collections by $19.9 billion per year.

One element of the estate tax intended to reduce its burden has gained renewed attention in recent years: the step-up in basis. The step-up in basis allows heirs to reset the cost basis of inherited assets upon receiving them. Critics argue that the step-up in basis allows wealthy individuals to shield certain assets from tax through the tax planning strategy known as “buy, borrow, die”—in short, securing loans against the value of assets rather than selling them until they can be passed on to heirs tax-free.

But while it is true that the step-up in basis, and the “buy, borrow, die” strategy it may enable, are hardly examples of ideal tax policy, the step-up in basis exists to protect taxpayers from even greater burdens arising from the estate tax and the fact that capital gains are not indexed to inflation. Should Congress seek to address “buy, borrow, die,” it could consider eliminating the estate tax and indexing capital gains to inflation. Doing so would allow the elimination of the step-up in basis without creating more problems than would be solved.

How did the TCJA change business taxes?

Rate. The TCJA lowered the corporate income tax rate to 21 percent, from the 35 percent rate it had been since 1993. This change is not subject to expiration so remains in effect unless Congress affirmatively changes it. With state corporate taxes, the combined corporate tax rate ranges from 21 percent (in states with no state corporate income tax) to 30 percent, and average 25.77 percent.

While the 35 percent federal corporate tax rate may have been competitive globally in 1993, corporate tax rates worldwide have dropped since then. Today, the average corporate tax rate is 23.45 percent, or 25.67 percent if weighed by gross domestic product (GDP), and 27.18 percent if looking only at the G-7 industrialized economies. Only nine countries in the world with a rate of 35 percent or higher: Comoros (50%), Suriname (36%), Argentina (35%), Chad (35%), Colombia (35%), Cuba (35%), Equatorial Guinea (35%), Malta (35%), and Sudan (35%). Corporate rate reductions peaked in the 1990s and 2000s, and have leveled off in recent years.

President Biden had proposed raising the corporate income tax to 28 percent, which would take the combined federal-plus-state corporate tax rate to 32.77 percent. Former President Trump has instead proposed a 20 percent rate, while some Republicans have mentioned a goal of reducing it further to 15 percent. Some criticize the U.S. corporate tax for seemingly raising less revenue as a share of the economy compared to other countries, although this is mainly because much U.S. business activity is by pass-through businesses such as partnerships, limited-liability corporations, and S corporations. Most business profits (61.8%) are taxed under the individual tax code but would be taxed as corporate income in other countries.

In addition to the corporate rate, U.S. corporations also face an alternative minimum tax of 15 percent on their “book income” if they report over $1 billion in profits to shareholders on their financial statements. This new book tax was enacted by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, and is unusual in that it taxes a base defined not by Congress but by an outside private entity.

The Pillar 2 international tax negotiations, if successful, would establish a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15 percent.

Expensing. A major pro-growth element of the TCJA was full expensing for short-lived capital assets, such as buildings and equipment. Under the previous tax code, businesses must calculate the cost of such investments by distributing the total cost over the expected life of the investment, as determined through depreciation schedules. By accounting for only a portion of the expense realized, business’s profits are artificially inflated in early years, thus increasing the tax liability.

The TCJA instead enacted 100 percent bonus depreciation, also known as full expensing, which allows businesses to deduct the full cost of short-lived assets in the year that the expense was incurred. This provision was not permanent and the percentage of bonus depreciation allowed under the TCJA has gradually declined. The TCJA allowed for 100 percent bonus depreciation for tax years 2018 through 2022, with a phase down to 80 percent in 2023, 60 percent in 2024, 40 percent in 2025, and 20 percent in 2026, before reverting to pre-TCJA depreciation in tax year 2027. The Tax Relief for Workers and Families Act (TRAFWA) of 2024 introduced by Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Representative Jason Smith (R-MO) would retroactively reinstate 100 percent bonus depreciation for tax years 2022 through 2025.

Full expensing achieves several key tax reform goals, such as restoring neutrality to the treatment of short-lived investments, reducing complexity of the tax code, and encouraging economic growth. Allowing businesses to fully expense the cost of capital investments in the year they are purchased frees up capital and enables businesses to immediately put it to productive uses. By deducting the cost over time, the expenditure would otherwise be reduced by inflation, disincentivizing investment. Full expensing is also far simpler for businesses to comply with than the byzantine depreciation system.

The revenue impact of full expensing is mostly a function of budget windows. While full expensing enables businesses to deduct the full cost of their investments immediately, depreciation defers it for years. The actual amount that businesses are able to deduct remains the same (albeit lessened slightly in terms of purchasing power by inflation in the case of depreciation), but full expensing acts as a major reduction in revenue since it frontloads deductions.

Extending or making permanent 100 percent bonus depreciation will continue to be vital to tax reform discussions moving forward, especially as state governments increasingly adopt the policy. President Biden’s Fiscal Year 2025 Budget Proposal would allow full expensing to expire in tax year 2027 as planned under the TCJA. Yet there has consistently been bipartisan support for extending or making the provision permanent, as recently shown through its inclusion in TRAFWA. Analysis by the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) shows that full expensing leads to increased investment in the manufacturing industry. Additionally, analysis by the Tax Foundation shows that private investment exceeded expectations after enactment of the TCJA. In November 2023, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, along with hundreds of affiliates, sent a letter to congressional leaders strongly supporting full expensing.

Territorial & Anti-Abuse Provisions. Historically, the United States had a “worldwide” tax on international income earned by U.S. residents, including realized, but undistributed, business profits held offshore. The tax rate was high: 35 percent. The effect of this draconian system could be mitigated by having a wholly owned foreign subsidiary whose taxes were offset by credits and not required to be repaid until repatriation (typically via dividends paid to domestic entities). During the 1950s, the situation became untenable as investors used tax shelters to shield investments. In response, President Kennedy sought reforms and “recommend[ed] that tax deferral be continued for income from investment in the developing economies.”The enacted reforms—and the temporary deal to defer taxes already due—lasted for decades.

Since 1962, Subpart F (26 U.S.C. §§ 951–964), applies to certain income of “controlled foreign corporations.” Overall, Subpart F rules were designed to negate the tax advantage from housing investment income in a controlled foreign corporation, particularly passive overseas income. The 1960s law allowed payment for taxes on certain international investment profits to be deferred, at the option of the investor, until the income was repatriated to the United States. It was never designed to be permanent, and the tax obligations were always counted as a deferral of accumulated tax obligations, not an excusal of them.

For decades leading up to 2017, there were extended policy discussions on various proposals for a permanent replacement of this system. Reform was necessary in part because the “temporary” provisions of Subpart F became their own problem. Businesses and investors understandably resisted repatriating income. Indeed, just before the TCJA’s passage, businesses were increasingly reorganizing overseas, or “inverting,” to avoid the U.S. corporate income tax altogether.

The TCJA was designed to replace this temporary deal, and its attendant problems, with something permanent. It switched the United States from a worldwide system to a territorial one that only taxes income earned within the country’s borders, lowered the overall corporate tax rate, and enacted a one-time mandatory repatriation tax (MRT) on accumulated overseas assets to transition from the old system to the new. This tax recently survived a constitutional challenge in Moore v. United States.

The move from a worldwide to a territorial system also necessitated other changes to ensure U.S. corporate competitiveness and protect the tax base. Ultimately, the TCJA created three new taxes applicable to certain foreign income and cross-border transactions: the global intangible low-tax income (GILTI) tax, the foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) tax, and the base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT).

GILTI: The U.S. was the first country in the world to enact a global minimum tax on corporate profits in 2017, a move that was promoted by former President Barack Obama. GILTI applies to the active foreign earnings of a U.S.-controlled foreign corporation (CFC) that are derived from intangible assets such as patents, intellectual property (IP), and software. In the calculation of the tax base for GILTI, businesses are allowed a ten percent exemption, known as qualified business asset investment (QBAI), to ensure that income from tangible assets is not included.

GILTI is applied as a top-up tax if companies are not paying at least that amount in tax on average across the jurisdictions in which they operate. Through the TCJA, corporations are allowed a 50 percent deduction on their foreign earnings, resulting in a minimum GILTI tax rate of 10.5 percent, which is half the U.S. corporate tax rate. The TCJA also limited the foreign tax credits (FTCs) claimed by many corporations to 80 percent of their value, which, in turn, raises GILTI’s effective maximum rate to 13.125 percent. Thus, companies should pay between a GILTI tax rate 10.5 percent and 13.125 percent. At the end of 2025, the 50 percent earnings deduction will be reduced to 37.5 percent, raising the minimum rate to 13.125 percent.

GILTI’s global averaging is an important element of the tax and contrasts with proposals from the Biden Administration for country-by-country calculation of a CFC’s foreign tax liability. Country-by-country calculation would result in higher tax revenue, as a corporation could be subject to a high GILTI tax if it earns high profits in one country, even if it suffers losses in every other foreign country it operates in. Global averaging therefore allows GILTI to be mostly agnostic to the country a corporation operates in. It also eases the compliance burden for companies and the enforcement burden for the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), as country-by-country calculation would require significantly more reporting and bookkeeping. Of note, the OECD is currently negotiating a global minimum tax under Pillar 2, which is calculated on a country-by-country basis.

FDII: FDII works with GILTI in a “carrot and stick” approach whereby FDII is the carrot. As GILTI taxes companies’ overseas earnings, FDII incentivizes companies to keep intangible assets in the U.S. through a lower tax rate. The income targeted by FDII is the income earned from foreign sources, essentially export income, that is contingent upon IP or other intangible assets that are based domestically. In calculating the income subject to FDII, companies are allowed a ten percent deduction for QBAI similarly to GILTI. This broadens the tax base by incentivizing companies to import intangible assets into the U.S., where the IRS has primary taxing jurisdiction. FDII works similarly to GILTI by allowing companies a 37.5 percent deduction on applicable income, bringing the effective FDII tax rate to 13.125 percent, on par with GILTI’s effective tax rate. At the end of 2025, the deduction will reduce to 21.875 percent, raising the effective tax rate of 16.406 percent.

BEAT: Whereas GILTI and FDII work together to incentivize companies to hold assets such as intellectual property within the U.S., which would expand the domestic tax base, BEAT works by targeting profit shifting. BEAT applies to a U.S. company or a U.S. affiliate of a foreign company with gross receipts of $500 million or more. These companies would be subject to BEAT if more than three percent of their total deductions come from payments to a related foreign corporation, such as interest payments or royalties for use of intellectual property, that shift profits abroad. BEAT acts as a minimum tax that companies must pay if their regular corporate tax liability is lower than the tax they would pay with BEAT calculation. To determine this, companies must add the disallowed interest, royalty, and other deductions back to their income and calculate their tax liability at the BEAT rate. The TCJA set this rate at 5 percent in 2018, 10 percent in 2018 through 2025, and 12.6 percent thereafter.

Throughout his term in office, President Biden has proposed changes to the TCJA’s international tax policies that would raise revenue while potentially reducing U.S. international competitiveness. Biden’s proposals would increase the GILTI minimum rate from 10.5 percent to 21 percent. As mentioned above, Biden would also change GILTI’s tax base from a global averaging system to a country-by-country calculation. Finally, Biden would reduce the 50 percent earnings deduction to 25 percent, allow companies to claim 95 percent of their foreign tax credits as opposed to the TCJA’s 80 percent, and eliminate the QBAI exemption.

The Biden Administration has also proposed repealing both FDII and BEAT. The Administration has proposed replacing BEAT with a new system dubbed Stopping Harmful Inversions and Ending Low-tax Developments (SHIELD), which would deny cross-border payments to related entities if they are subject to a low effective tax rate. A significant problem with this proposal is that the default tax rate would be the Administration’s proposed GILTI rate of 21 percent, which is higher than the corporate tax rate in other jurisdictions. Biden has also proposed replacing BEAT with the Undertaxed Profits Rule (UTPR) that is part of the OECD’s Pillar 2 negotiations. UTPR faces serious concerns in part due to its structure as an extraterritorial enforcement mechanism, leading the OECD to offer a safe harbor for compliance through administrative guidance. There are also questions about the revenue that would be raised by the UTPR and Pillar 2 more broadly.

Changes to Interest Deductibility. Businesses can typically deduct the cost of interest payments, and the TCJA put restrictions on interest deductibility that become more stringent over time. The TCJA limited the amount of interest that a business can deduct to 30 percent of percent of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA), starting in 2018. In 2022, interest deductions were further limited to 30 percent of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT).

Allowing for a deduction on interest creates a preferential treatment of debt over equity in the tax code. Yet the use of EBIT, rather than EBITDA, has faced criticism for being unique among OECD nations and potentially resulting in job losses. Disallowing deduction of depreciation and amortization can adversely affect job creating industries that make long-term investments, such as manufacturing, information technology, transportation, and mining. Despite this criticism, experts note that the effect of interest deductibility on investment decisions is relatively modest, especially compared to other TCJA policies, such as full expensing.

Research & Development. For over six decades prior to the TCJA, companies could deduct R&D expenses in the year that they are incurred, freeing up capital for the business to use elsewhere. The TCJA changed this to require amortization of R&D expenses over five years, starting in 2022. Amortizing R&D over time instead of fully expensing the cost when it is incurred raises the cost of innovation, which both hurts the U.S. economy and makes American research-intensive industries less competitive internationally.

There is broad bipartisan consensus that the treatment of R&D should be fixed, and a provision to do so was included in the TRAFWA. While allowing for the proper expensing of R&D costs has a very significant impact on the economy, certain businesses can also claim a tax credit for R&D expenses. This nonrefundable credit was made permanent in 2015 and expanded for small businesses in 2022. Some legislation that has been introduced both fixes R&D expensing and expands R&D tax credits further for small businesses.

Threat: Digital Service Taxes & Pillar 1. Alongside the OECD’s global minimum tax proposal, ongoing international tax negotiations are also attempting to address digital services taxes. The digital economy is a critical element of international taxation, as services provided online easily transcend borders, leaving questions about where a business technically operates. In general, U.S.-based companies such as Facebook, Google, and Amazon are under the taxing authority of the IRS regardless of where their customers are based. However, countries have increasingly adopted digital services taxes (DSTs) that target foreign digital service providers earning revenue in their jurisdiction.

DSTs are not what one would typically consider a tax, first and foremost, because they are extraterritorial. They also often target gross receipts rather than profits and are discriminatory against digital services. Countries such as France and Canada have targeted mostly American technology companies with DSTs, raising significant concerns for international trade.

The OECD’s solution for DSTs comes in the form of Pillar 1, which would reallocate taxing rights of certain multinational corporations’ profits and develop new transfer pricing rules. Pillar 1 has faced criticism for being an inadequate solution as it may not result in the full elimination of DSTs. The Biden Administration has provided little clarity to Congress and the public regarding the benefit that the U.S. would receive from agreeing to Pillar 1, which would require an act of Congress for the U.S. to comply. Furthermore, there are still concerns from countries, including the U.S., about various elements of the proposal, which have stalled the agreement and led to the reintroduction of harmful DSTs.

Employer paid leave credit. The TCJA created a tax credit for employers providing paid family and medical leave under Section 45S of the tax code. This credit can be claimed by employers providing paid leave of at least 50 percent of normal wages to employees with a minimum credit of 12.5 percent of wages paid. If an employer provides paid leave equal to the employee’s full normal wages, the maximum credit amount is 25 percent of wages. This credit can be claimed for up to 12 weeks per employee and was originally set to expire at the end of 2019, but has been subsequently extended through the end of 2025. This program was originally introduced as legislation by Senator Deb Fischer (R-NE) and is only available for the paid leave of lower-income workers.

Corporate state and local tax (SALT) deduction and individual SALT workarounds. The TCJA’s changes to the treatment of state and local tax (SALT) deductions for individuals had an effect on the business community, as well. Since the owners of S corporations and partnerships pay the business’s tax liability at the individual level, these businesses face the SALT cap. C corporations, on the other hand, pay tax at the business entity level, which does not face a SALT cap. In response to this disparity, some states have enacted a “pass-through work around” to spare pass-through business owners from the SALT cap. Some analysis suggests that these SALT workarounds reduce federal revenue by $20 billion annually. While the Department of the Treasury suggests that this is allowable, tax groups have requested further guidance on the matter.

Opportunity Zones. Opportunity zones were included in the TCJA as an incentive for investment in underserved communities. An opportunity zone is defined as a low-income census tract designated by a state to receive special tax capital gains tax treatment. Investors can defer their capital gains tax liability if those gains are invested in a qualified opportunity fund (QOF) within 180 days. This deferment lasts until the investment is sold or exchanged, or until December 31, 2026, which is when the opportunity zones provision of the TCJA expires. The TCJA includes additional tax benefits, such as steps up in basis for gains held in a QOF for five and seven years, and permanent waiver of tax liability for gains incurred after investment in the QOF if held for ten years.

The evidence as to whether opportunity zones have been successful in spurring investment in underserved communities is still unclear. In 2022, the Government Accountability Office released a study where investors provided mixed responses as to whether they would have made the same investment regardless of the opportunity zone incentive. Importantly, investors also recognized that the structure of the tax deferral placed more emphasis on the economic viability of the project than tax credits would have. Analysis by the Tax Foundation points out several challenges in determining the true benefit such a program would have to a community’s economic development, labor force, and prices. Of note, Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR), Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, has previously opened an investigation into the program’s benefits, citing lack of transparency in reporting on QOFs. GAO has recommended that Congress direct the Department of the Treasury to collect more data on opportunity zones.

Pass-Through Business Deduction for Qualified Business Income (Section 199A). The TCJA created new deductions for pass-through businesses to deduct up to 20 percent of such business income from federal income taxes, up to a maximum income level. Section 199A was designed (disputably) to equalize the tax rate between C corporations and other business forms, and is currently set to expire at the end of 2025.

This provision saves small businesses a great deal in taxes paid, but does require additional work from taxpayers to claim it, estimated at $1.3 billion in compliance costs. Policy options for Congress include allowing the deduction to expire, permanently extending it, or modifying with an alternative method of taxing pass-through businesses. Alternatives include reform the existing Section 199A to simplify it, taxing all C corporations on the same terms as Section 199A or vice versa, or broader restructuring of business taxes.

What Other Changes to Taxes Have Occurred In Recent Years?

1099-K Reporting. New 1099-K reporting requirements are another tax change upcoming in 2025, despite not being part of the TCJA. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021, passed and signed into law by Democrats on a partisan basis, included a pay-for provision changing the reporting threshold for issuance of a 1099-K form. These forms are supposed to be provided by third-party settlement organizations (TPSOs), such as banks, that process card payments for individual merchants accepting card payments to ensure that income is being properly reported. Prior to ARPA, the threshold for issuing a 1099-K was 200 transactions and $20,000 in gross value of sales to ensure that mainly business transactions were captured by 1099-K filing requirements.

ARPA significantly reduced the threshold for 1099-K filing to a mere $600 with no transaction threshold. This would cause potentially millions of taxpayers with nontaxable transactions, including those conducted via popular TPSOs, such as Venmo and PayPal, to receive a 1099-K form. The new requirement will create confusion and paperwork burdens for both the taxpayer and the IRS. In recognition of the policy’s problems, the IRS has continuously delayed implementation of the law which was supposed to take effect in 2022. It will now “phase in” implementation at an arbitrary $5,000 threshold in 2025, despite not having authority to change the threshold.

Employee Retention Tax Credit (ERTC). The Employee Retention Tax Credit (ERTC) was implemented in 2020 to help small businesses retain workers throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. The ERTC provided for a tax credit for wages paid by the employer per employee in 2020 and 2021.

Unfortunately, there is strong evidence that ERTC claims, especially those filed long after the end of lockdowns, became ripe with fraud. In August 2021, the IRS issued Notice 2021-49, which prohibited small business owners from claiming ERTC if they have a brother, sister, parent, or child, regardless of whether this individual was involved in the business. In other words, the IRS’s Notice essentially prohibited most individuals from claiming the ERTC. Even worse, the IRS backdated this Notice to 2020 and required any person who claimed the ERTC credit, but had a relative, to pay back any amount claimed. In September 2023, the IRS announced a moratorium on processing any further ERTC claims, but still receives 20,000 new claims per week.

Tax on Stock Buybacks. Motivated by the perception that stock buybacks are an economically unproductive means by which corporations reward shareholders at the expense of investing in their business operations, Congress included a new 1 percent excise tax on stock buybacks as part of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Beginning in 2023, publicly traded corporations owed the tax on repurchases of any of their own shares. President Biden has called for quadrupling this tax rate to 4 percent.

The perception that buybacks are an economic burden misunderstands their function, however. Implicit in this criticism is the idea that buybacks are a direct alternative to capital investment—that corporations can either choose to reward their shareholders or play the long game and grow their businesses. But the evidence points to the idea that corporations engage in share repurchases after exhausting available opportunities for productive investment, because stock buybacks are more akin to a corporation depositing money in a savings account than “spending” it. Buybacks often result in increased share prices (though the relationship is less direct than often described), thereby rewarding shareholders.

By buying back their shares, corporations are simultaneously giving themselves room to sell those repurchased shares in the future and returning capital to the broader investment pool, creating more for other businesses that do have productive investments left to make. If buybacks increase share value, they benefit millions of Americans who own stocks, mutual funds, or retirement accounts. 58 percent of Americans owned stock as of the last Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances in 2022, while just over two-thirds of working-age adults participated in a retirement plan of some sort. That aligns with the percentage of Americans who owed income taxes that year (about 60 percent).

Energy Tax Credits in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 focused heavily on climate change and renewable energy, with tax credits and other incentives estimated at the time to cost nearly $400 billion. Tax credits in the law were geared toward clean and renewable electricity, fuel, residential energy, and vehicles. Other incentives included community-based block grants for environmental justice, transportation access, and climate resilience, as well as funds for air quality and other environmental programs. Many of these subsidies included burdensome restrictions, such as the electric vehicle credit’s domestic purchasing requirements, that are strongly opposed by America’s foreign trade partners. The electric vehicle credit also faces criticism for being regressive, as its value mainly benefits high-income taxpayers, which could be true for other IRA energy programs as well.

The expected cost of these subsidies has increased substantially since the time of enactment. For example, Penn Wharton Budget Model (PWBM) estimated the cost of these provisions to be $384.9 billion over a 10-year window at the time of enactment, but later updated this estimate to an incredible $1.045 trillion over that time. Other experts have estimated that the cost of the IRA’s energy tax subsidies could amount to $1.8 trillion. Earlier this year, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) increased the projected outlays for IRA energy credits over the 10-year window by $124 billion, largely due to regulations subsequently released by the Treasury. Former President Donald Trump has promised to repeal these tax credits if he is reelected to the presidency, which has also been supported by some congressional Republicans as a means of paying for substantive tax reform.

Extenders. A number of federal tax provisions regularly expire each year and renewed, or extended, near the end of each calendar year (or after). For example, in 2019, over 40 provisions were set to expire, and in December Congress extended most of them through 2020 and some through 2021. Many of these provisions have large price tags which makes it difficult under budgetary rules for Congress to enact them permanently.

Not all extenders are created equal: some primarily help well-connected industries with favorable tax treatment, while others are more broad-based and move the tax code toward better tax policy.

Tariffs. From the conclusion of World War II to the start of the 21st century, the United States led successful efforts to reduce U.S. and foreign barriers to trade. From 1994 to 2009 alone, average tariffs on U.S. exports fell from 13.4 percent to 5.5 percent. Further progress stalled as the United States stopped negotiating new trade agreements and then doubled U.S. tariffs during the Trump and Biden administrations. President Biden’s trade actions will cost Americans the equivalent of $2,950 per U.S. household over the next 10 years. President Trump's proposed across-the-board 10 percent tariff would further increase this cost and reduce exports.

Tariff increases undermine TCJA benefits. The government collected more than $240 billion in new, regressive import duties from 2018 through June 2024, the equivalent of $1,849 per household. Foreign retaliatory tariffs imposed on U.S. exports inflicted additional damage on the economy. Further increases should be avoided, and calls to increase tariffs to offset other tax cuts should be rejected. Any discussions should be reality-based, starting with the fact that tariffs are paid by Americans and acknowledging that it’s impossible to replace the individual income tax with tariffs based on current spending levels.

How Has IRS Funding and Oversight Changed Since the TCJA?

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 approved $80 billion in additional funds to the IRS over ten years. Congress’s passage of the IRA sought to propel the IRS into the modern century as an administration. A series of four reports by the Taxpayers For IRS Transformation (Taxpayers FIRST) project coordinated by NTUF reviewed IRS spending plans and priorities.

From Lag to Leap: A Roadmap for Successful IRS Modernization. The IRA’s funds were intended to help IRS’s operations enter the modern era. However, the IRS has not been clear on the specifics of how it intends to remedy these issues. In response, we urge 1) an enhanced modernization plan coupled with a cost analysis; 2) more transparent metrics and updates; 3) acceleration of the pace of modernization, using some of the IRA’s funds to support these efforts; and 4) adding an accountability entity to the IRS’s structure.

Call to Action: Crafting a New Taxpayer Service Experience. Although the bulk of the IRA was reserved for enforcement, the IRS still faces serious customer service challenges such as lack of transparency, delayed resolution for victims of identity theft, limited number of calls answered, delayed returns processed, and subpar online tools. Given these problems with the IRS’s customer service, we urge 1) ensuring that any modernization effort also improves customer service; 2) the IRS to adopt more metrics, especially those that focus on outcomes versus inputs or outputs, and make these studies available for the public; and 3) improved services for historically underserved communities and economically vulnerable populations.

Minding the Gap: Recommendations for Assessing, Addressing, and Ameliorating the Tax Gap. The IRS, somewhat annually, releases its Tax Gap Report, which estimates the difference between taxes owed in a year and taxes paid on time, while the net tax gap reflects the figures in the gross tax gap. However, there is a lag in the IRS’s underlying estimates and the IRS’s methodology is not transparent. To remedy these issues, we urge 1) that the IRS report the tax gap in a data context; 2) formalize and standardize the tax gap’s methodology; 3) conduct studies on how to improve the tax gap’s comprehensiveness; 4) set clear goals and metrics for addressing the tax gap; 5) quantify benefits stemming from improved taxpayer services; 6) provide timelier and clear guidance on tax compliance; and 7) consolidate the duplicate tax gap pages which exist on the IRS website.

Shaping a Future of Fairness: Proposals to Safeguard and Strengthen Taxpayer Rights. As Congress increases the size and power of the IRS, it should also increase taxpayers’ rights. Currently, the complexity of the tax code costs taxpayers billions in compliance costs. Even if a taxpayer does comply, letters from the IRS are not clear as to the taxpayer’s obligations or rights. Appeals are often not impartial and favor the IRS in many ways. In response to these problems, we urge 1) that Congress elevate the importance of taxpayer rights in federal law; 2) that the IRS elevate taxpayer rights in its publications, website, and physical locations; 3) that the IRS revise its notices so that taxpayers are able to easily understand why they are receiving the notices and their appeal rights; 4) continued IRS compliance with the requirement that supervisors approve any penalties; and 5) that the IRS should actively work to ensure its Office of Appeals is independent and work to expand the Taxpayer Advocate Services Flexibility.

Conclusion

In addition to the numerous TCJA provisions expiring at the end of 2025, there are numerous other tax policies that have changed since 2017 or that have been proposed. The estimates of varied revenue increases and losses take on added significance due to the growing national debt, size of federal interest payments, and the costs associated with expiring TCJA provisions. Policymakers will likely consider options in all of these areas as they determine how to extend the pro-taxpayer, pro-growth parts of the TCJA in a responsible manner.