On October 1, Minnesota Governor Tim Walz and Ohio Senator J.D. Vance are set to clash over who gets to be one spot removed from the highest executive position in the country. But while the debate will cover a range of topics, it’s worth noting that Tim Walz already holds executive authority over a state — and that state’s residents keep trying to get out.

In recent years, most states have sought to make their tax climates more competitive and taxpayer-friendly. Since 2021, 28 states have cut individual income taxes, while others have reduced their corporate income and sales tax rates.

But ever since Tim Walz took office in the beginning of 2019, Minnesota has taken the opposite path. Already the governor of a state with a relatively high top individual income tax bracket, Walz signed into law a new payroll tax to fund paid family leave, a new surtax on capital gains and investment income, and a phase-out of standard and itemized deductions above an income threshold. Under Walz, Minnesota legislators also passed legislation expanding the scope of the state’s corporate income tax code to capture more international income, while an effort to institute worldwide combined reporting based on faulty data narrowly failed.

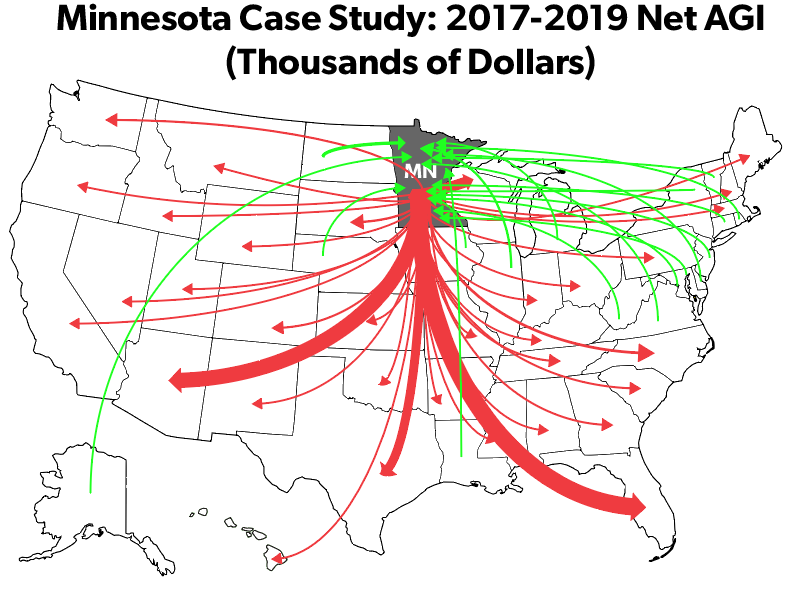

Given this predilection for tax hikes, it’s no surprise that some former Minnesota residents have chosen to seek greener pastures. While Minnesota has been a state that loses taxpayers on net to domestic migration for some time, the trend accelerated after Walz became governor.

If You Can’t Keep Them In Minnesota...

The IRS periodically releases data showing changes in taxpayers’ residency status on their federal income tax returns between two years. This data helps to see what states taxpayers (and their tax dollars) find more desirable, and what states taxpayers want to leave.

The latest IRS release covers the change between individual income tax returns filed in 2021 and returns filed in 2022. Tax returns cover the previous year’s tax information, meaning that returns filed in 2022 actually refer to taxpayers’ residency status in 2021. In other words, the 2021–2022 release of IRS data actually tells us where taxpayers moved to and from between 2020 and 2021. To minimize confusion, we will refer from here on to the years covered by the tax returns, not the years the returns were filed.

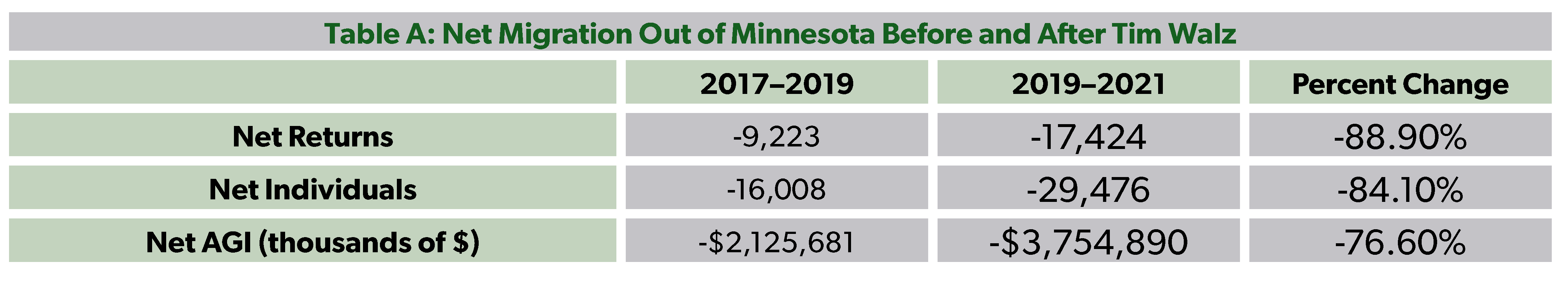

Table A shows the change in net migration out of Minnesota between 2017 and 2019 (before Tim Walz became governor) and between 2019 and 2021. Unfortunately, IRS data is not yet available for the rest of Walz’s governorship.

Not only has Walz done nothing to stem the tide of Minnesotans leaving the state, the trend has actually accelerated rapidly since he became governor. While the change in Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) could be partially attributed to inflation, this cannot account for the fact that households left the state at a faster rate in the first two years of Walz’s governorship than in the last two years of his predecessor.

It’s important to note that the pandemic plays a major role in this data as well. The spike in remote work due to the pandemic caused major shifts in migration patterns all around the country, not just in Minnesota.

However, this fact hardly absolves Minnesota policymakers of responsibility. Across the country, the pandemic merely accelerated existing patterns of migration of taxpayers away from high-tax states and into low-tax states. After all, there is little reason why these newly-remote taxpayers could not move to Minnesota rather than away. Neither can Minnesota’s frozen temperatures explain the state’s consistent outflow of taxpayers, as similarly-frigid states like Wisconsin and Montana have not faced the same problem.

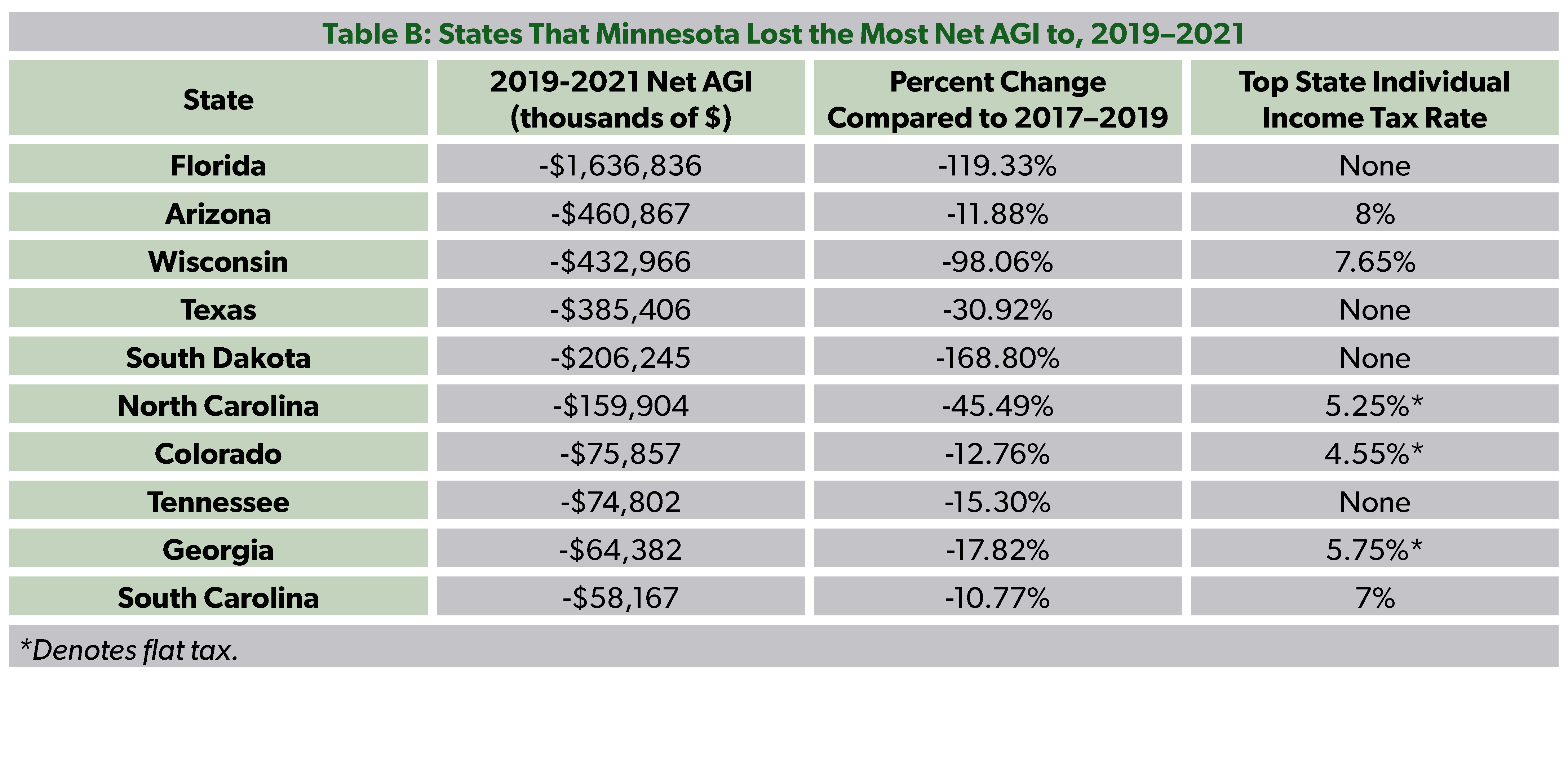

Looking at the states that Minnesotans preferred to move to while Walz was governor, taxes certainly seem to be a major factor in Minnesota’s accelerated exodus. Table B shows the ten states that benefited most from the net outflow of Minnesota AGI. It also shows the top individual income tax rate in that state in 2021, compared to Minnesota’s 9.85 percent.

As Table B shows, each of these states had a lower top individual income tax rate than Minnesota in 2021. But migrants may also have anticipated the possibility of tax cuts in some of these states, tax cuts that were unlikely to happen in Minnesota. And indeed, many of these states have subsequently reduced their top tax bracket. Arizona dropped its 8 percent bracket in favor of a 2.5 percent flat tax and North Carolina, Colorado, and Georgia reduced their flat tax rates down to 4.5 percent, 4.4 percent, and 5.49 percent respectively. South Carolina also cut its top individual income tax rate from 7 percent to 6.4 percent. Wisconsin, the only state above that did not cut taxes, only failed to do so because the state’s Democratic governor vetoed a $3 billion tax cut package passed by the legislature.

. . . Bring Minnesota to the Whole Country

Unfortunately, other Americans across the country may soon learn what recent Minnesota emigrants already knew. The Harris/Walz campaign platform includes a litany of proposed tax increases, including raising the top individual income tax bracket back to 39.6 percent, increasing tax rates on long-term capital gains, taxing unrealized capital gains at death, just to name a few. In all, the Tax Foundation estimates that the Harris/Walz tax agenda would increase taxes by $1.7 trillion over the next decade after factoring in other proposed tax cuts and credits.

All those tax hikes have an effect on the economy. That same Tax Foundation estimate anticipates economic effects including a 2 percent reduction in long-run gross domestic product (GDP), wages declining by 1.2 percent, and 786,000 lost jobs.

Conclusion

While Minnesota residents fed up with being overtaxed at least have the option of packing up and leaving for another state, the solution to excessive federal taxation is far less straightforward. But should Walz make it to the Naval Observatory, American taxpayers should know what to expect.

State migration data provides important context for what matters to taxpayers in choosing where to reside. And while taxes are only one factor and not always the deciding one, years of data show a clear pattern of taxpayers leaving high-tax states and heading to low-tax states — a pattern better explained by tax rates than any other factor.

It’s not only state governors and legislators that should pay attention to what fed-up taxpayers are telling them. Taxpayers are tired of being overtaxed, and ready for relief — not repackaged versions of the same tax increases.