Introduction

Costs for the presidential library system have risen to over $100 million a year. The system, originally envisioned by Franklin D. Roosevelt, has grown into an expansive network of 14 facilities preserving the records of America’s former chief executives. While the system ensures public access to presidential archives, its costs—borne largely by taxpayers—cast doubt on the system’s fiscal sustainability. Over time, operational expenses, staff requirements, and the sheer volume of both physical and digital records have increased significantly, challenging the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to balance its mission of transparency with fiscal responsibility.

Origin of the Presidential Library System

The modern presidential library system was initiated under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Before this system, presidential documents were considered the personal property of each president. At the time, only two presidential libraries existed: a library of Rutherford B. Hayes’s records maintained jointly by the state of Ohio and a foundation, and a library for Herbert Hoover’s records established at Stanford University. Roosevelt envisioned a privately built library for his records, which was transferred to the federal government in 1940 under a law passed in 1939.

The Presidential Libraries Act was enacted in 1955 to establish a formal system for preserving and administering the historical documents of presidents. Following tradition, presidents and their supporters privately financed the construction of these libraries. The Act encouraged presidents to donate their papers and associated materials, land, or facilities to the federal government, ensuring these historical items would be preserved and made accessible to the public. Initially, the depositories were administered by the General Services Administration (GSA) until a 1984 law transferred this responsibility to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

The Presidential Records Act (PRA) of 1978 provided that, as of January 20, 1981, all presidential and vice presidential records would become the property of the United States government. Upon leaving office, the Archivist of the United States assumes possession of all documents. These presidential records would still be held in the library system, as per the Act, but the operations costs of these libraries were now fully in the hands of the federal government and, as a result, the taxpayers.

The rising costs associated with an ever-expanding library system soon became a concern. The Presidential Libraries Act of 1986 prescribed that, going forward, endowments would be required to cover at least 20% of the costs incurred by the government in acquiring land, facilities, or equipment associated with the library. Most of the private funds used to finance the library are raised through Presidential Library Foundations. The foundations are all structured as tax-exempt charities. Subsequent laws increased the cost covering requirement to 40% in 2003 and then 60% in 2008. Additional endowment requirements are imposed on library facilities that exceed 70,000 square feet.

The Current Presidential Library System

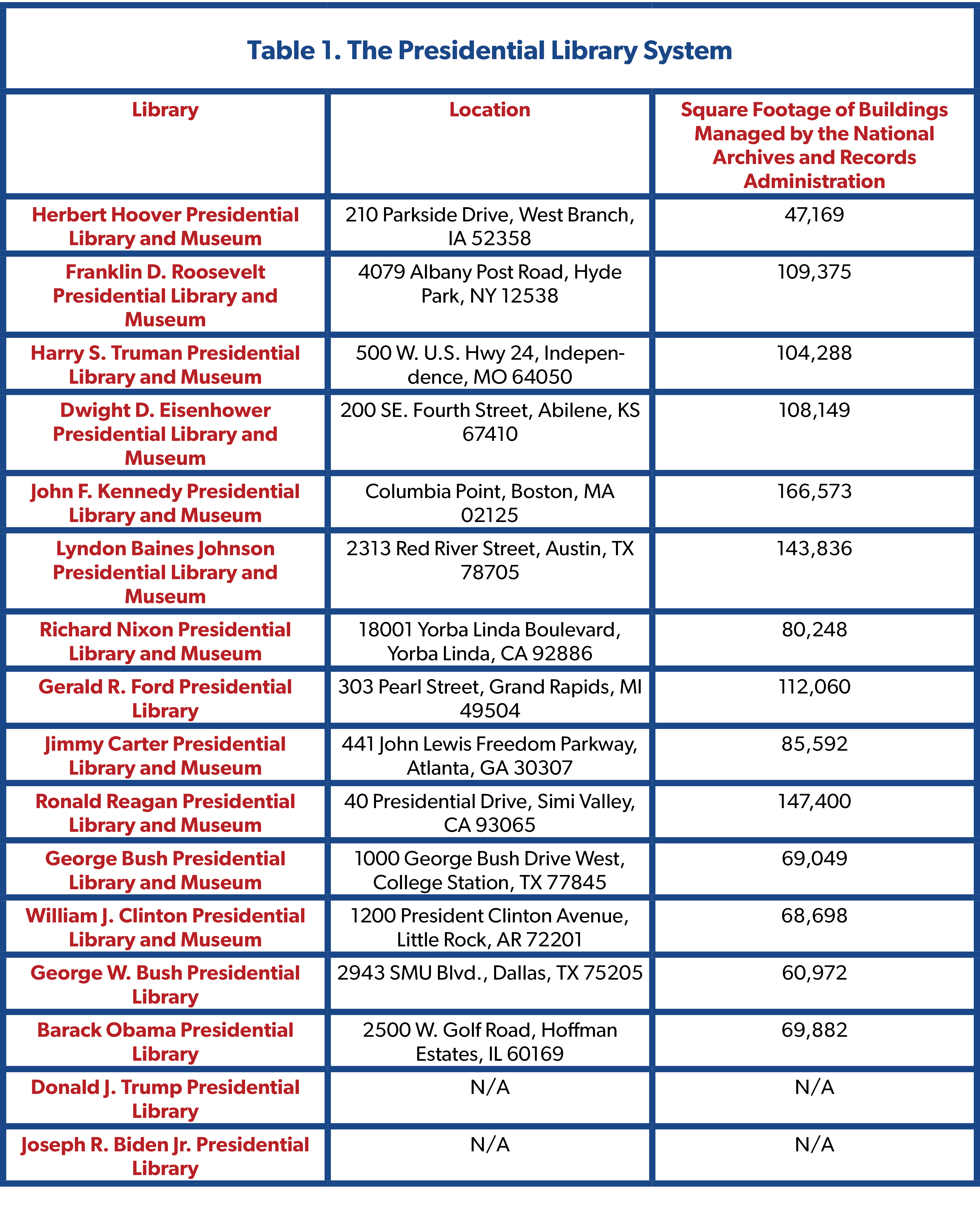

Below is a table of the libraries currently in the presidential library system, along with the square footage of the facilities managed by NARA. The John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston is the largest at 166,573 square feet, while the smallest managed by NARA is the William J. Clinton Library in Little Rock at 68,698 square feet.

On Wednesday, January 20, 2021, NARA launched a website for the Donald J. Trump Presidential Library. President Trump had not finalized plans for a physical library for his documents before being reelected in 2024. Plans are also to be determined for the Joseph R. Biden Jr. Presidential Library. NARA assumed custody of the records and artifacts of the Biden administration and has recently launched a library website.

Budgetary Impact

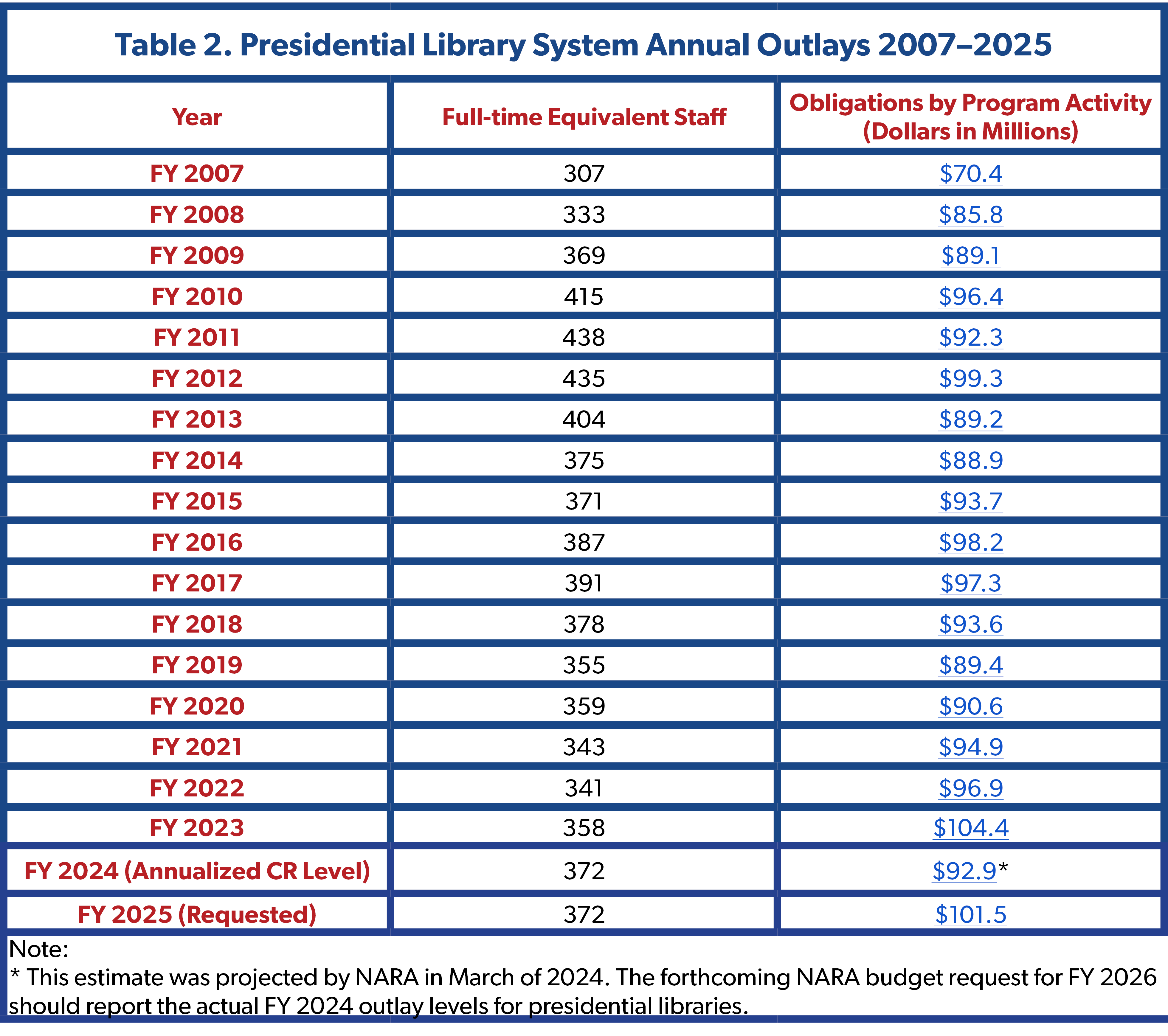

NTUF was able to find top-line budget totals for the presidential library system back through 2007. The data shows an overall increase in spending obligations and staffing levels from FY 2007 to FY 2025, with fluctuations along the way. Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) staff peaked at 438 in FY 2011, but declined in subsequent years, stabilizing around 350 to just over 370 FTEs in recent years.

NTUF was able to find top-line budget totals for the presidential library system back through 2007. The data shows an overall increase in spending obligations and staffing levels from FY 2007 to FY 2025, with fluctuations along the way. Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) staff peaked at 438 in FY 2011, but declined in subsequent years, stabilizing around 350 to just over 370 FTEs in recent years.

Outlays can vary from year to year, depending on new additions to the system, maintenance work on existing facilities, or digitization initiatives. Outlays saw a generally steady rise from $70.4 million in FY 2007 to $104.4 million in FY 2023, with some variability. The 2019 level dropped after a lower budget request planned to “increase efficiency and effectiveness of Presidential Libraries” by consolidating some services and reducing staff through attrition.

As noted in the table, the total outlays for 2024 are uncertain given the delays in passage of FY 2024 appropriations when NARA prepared the estimate in March of 2024. The next budget request for FY 2026, expected to be published this spring, will report the actual FY 2024 outlays. The FY 2025 budget request represents a notable increase from FY 2024, reflecting $101.49 million in obligations and maintaining staffing at 372 FTEs. The trend indicates gradual growth in spending despite staffing adjustments.

Program Costs per Presidential Library

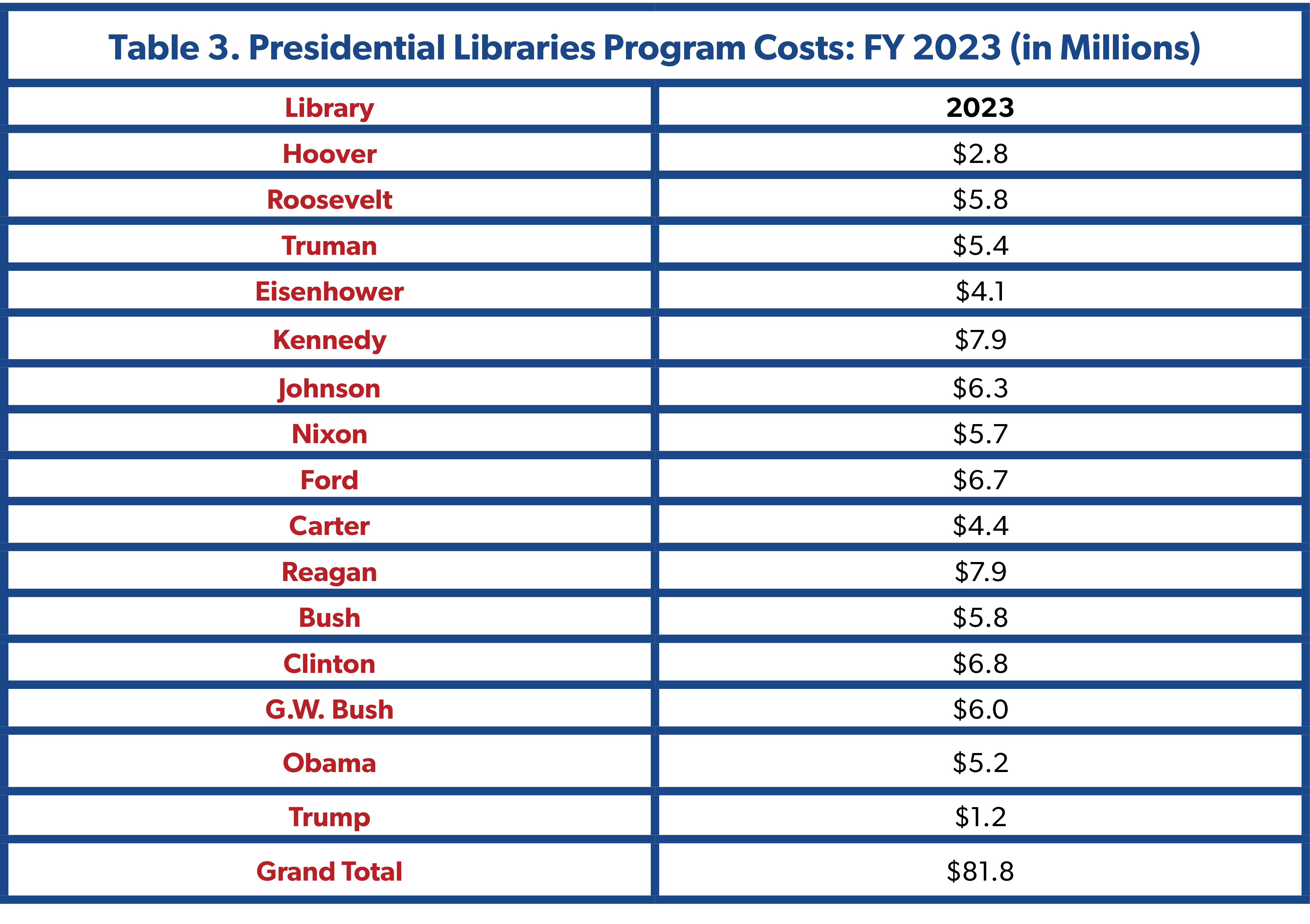

Recent NARA budget documents do not provide a break out of outlays per presidential library. Upon request from NTUF, NARA provided FY 2023 program obligations. NARA notes that this information excludes additional funding of $22.68 million allocated to cost of management and administration, including information technology, human resources, procurement, and financial management.

In FY 2023, the costs of operating the Presidential Libraries Program varied significantly across libraries, totaling millions in taxpayer-funded expenses. The John F. Kennedy Library topped the list at $7.94 million, closely followed by the Ronald Reagan Library at $7.87 million. Other libraries, such as the Herbert Hoover and Donald Trump libraries, incurred much lower costs at $2.76 million and $1.23 million, respectively. As noted above, total outlays for 2023 topped $104 million. The figures in table 3 exclude additional costs including records and communication services, and additional services provided by non-federal contractors.

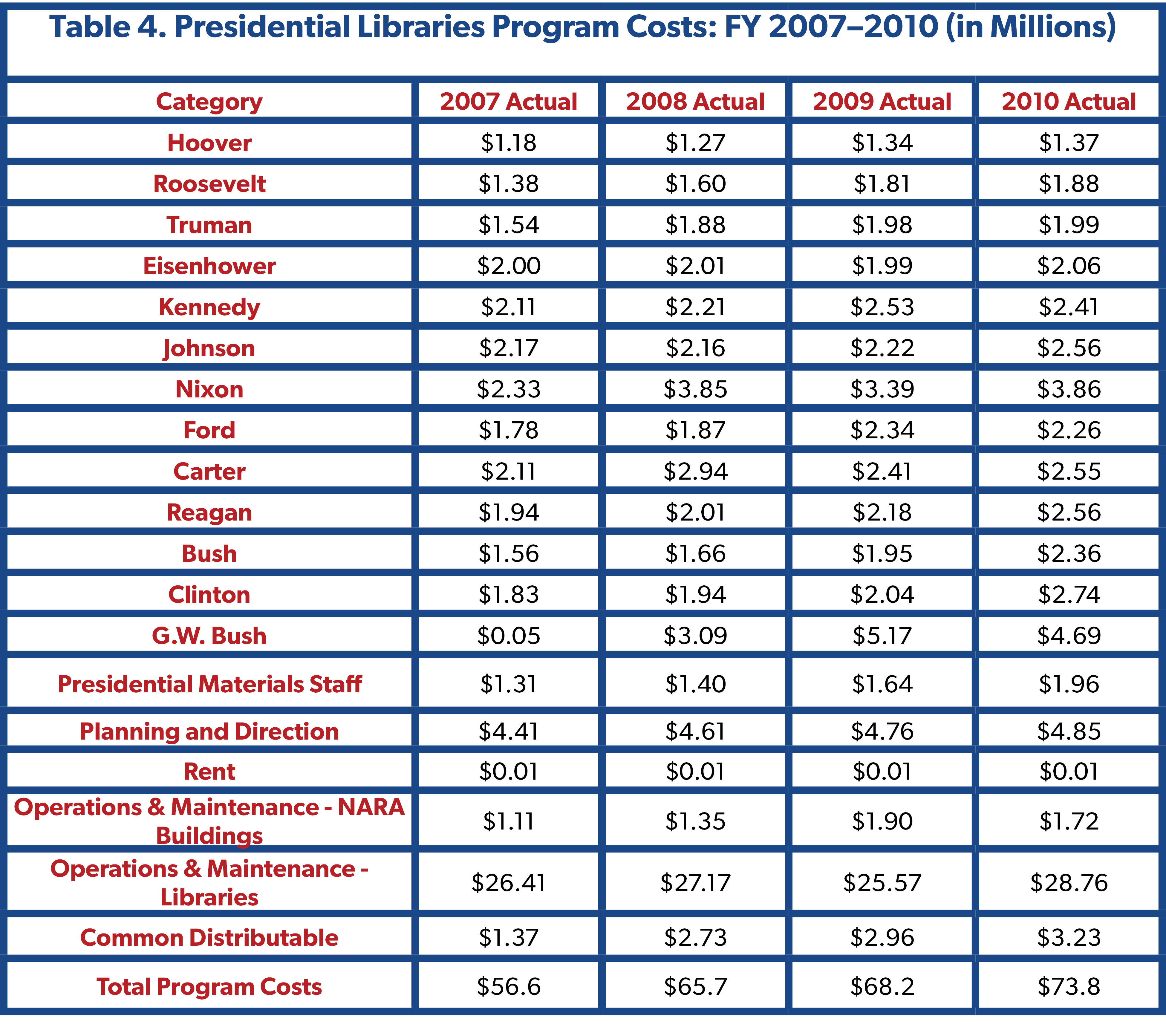

This information had been previously published in some of NARA’s annual performance budgets. Table 4, below, shows the program obligations for FYs 2007 through 2010.

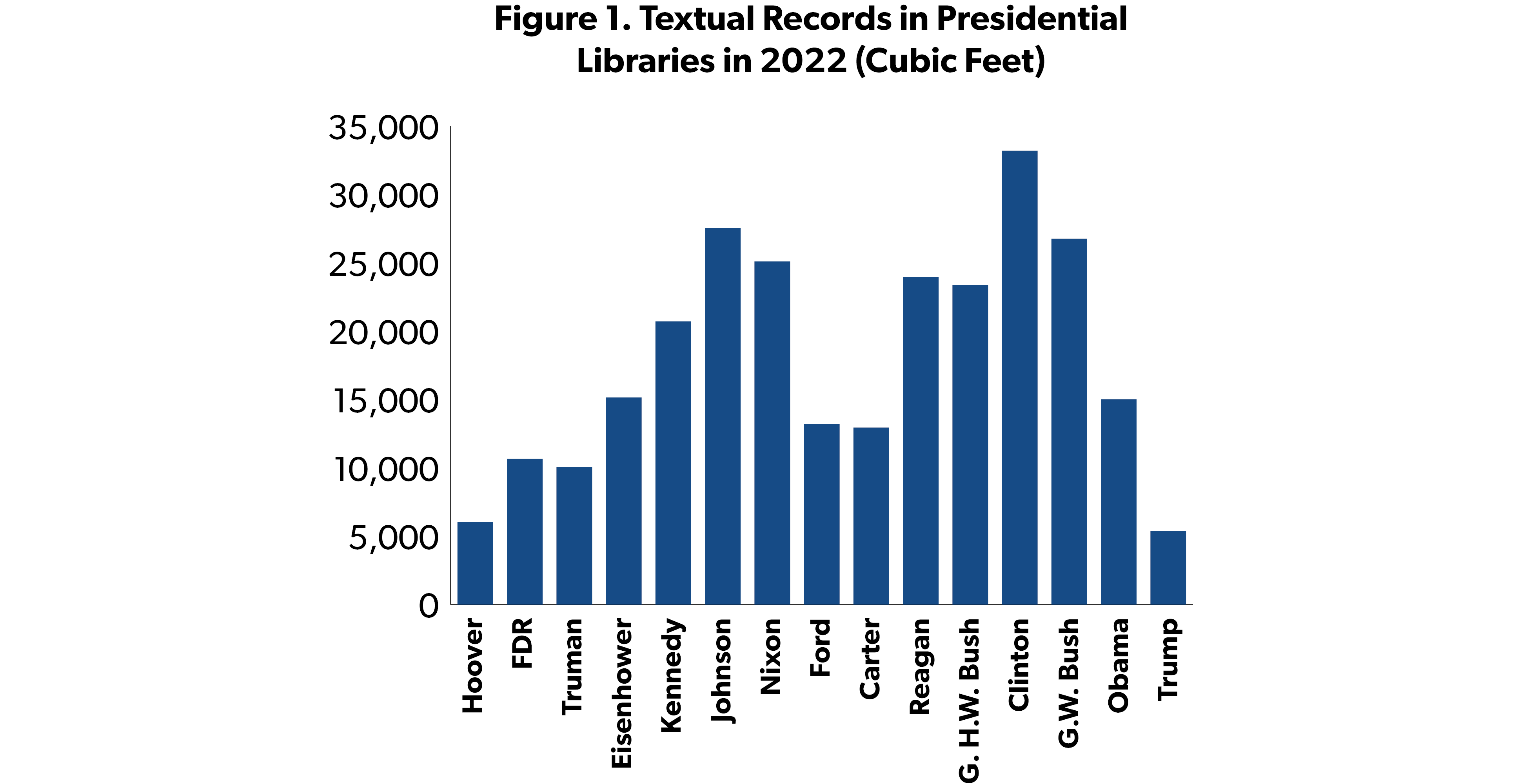

The presidential library system continues to expand every four to eight years, adding more responsibilities to NARA, including the management of facilities, documents, and records. As of 2022, NARA reports that it had a total of 269,114 cubic feet of textual records in the library system—an increase from 256,707 in 2008). To put this in perspective, that latest volume would fill three Olympic-sized swimming pools. Figure 1, below, illustrates the distribution of records across each presidential library.

management of facilities, documents, and records. As of 2022, NARA reports that it had a total of 269,114 cubic feet of textual records in the library system—an increase from 256,707 in 2008). To put this in perspective, that latest volume would fill three Olympic-sized swimming pools. Figure 1, below, illustrates the distribution of records across each presidential library.

There is also an increasing amount of digital records being amassed under recent administrations according to the NARA statistics:

Clinton: 4 terabytes

George W. Bush: 80 terabytes

Obama: 250 terabytes

Trump (first term): 250 terabytes

Starting with former President Reagan, records are subject to Freedom of Information Requests five years after the president has left office. Additional restrictions apply to certain records from five to twelve years. NARA notes the management challenges presented by this:

Starting with former President Reagan, records are subject to Freedom of Information Requests five years after the president has left office. Additional restrictions apply to certain records from five to twelve years. NARA notes the management challenges presented by this:

NARA must review all Presidential papers page-by-page, to identify and redact national security and other restricted information, which is an extremely resource-intensive process. NARA has a FOIA backlog of an estimated 183 million pages at the George W. Bush Library and 128- million-page backlog at the Barack Obama Library. NARA is currently only able to process approximately 500,000 pages per year in response to FOIA requests for Presidential records.

As facilities in the system age, NARA must finance capital improvements. For example, the 2025 budget request includes major projects plans for two libraries:

$2.3 million for the replacement of the electrical distribution system at the Nixon Library.

$2.1 million to complete a design project for the replacement of the electrical generator and switchgear at the Hoover Library, and

$1.8 million for the replacement of several air handling units at the Hoover Library.

There was also a recent pair of bills introduced in Congress to provide additional funding for presidential libraries outside of the system. For example, in 2024, Senator John Hoeven (R-ND) introduced the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library Museum Artifacts Act (S. 4129) to provide up to $50 million in grants through the Department of the Interior to help establish a new library for Theodore Roosevelt. This was passed by the Senate in December of 2024, but the House did not vote on it. Representative Kelly Armstrong (R-ND) introduced similar legislation in the House, however the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library Act (H.R. 7992) did not specify the amount of grants to be provided.

Opportunities for Reform

As the presidential library system expands, lawmakers may want to consider options to contain costs. The Barack Obama Presidential Library presents one model. The Obama Foundation decided its records would be fully digital. However, in anticipation of the Obama Library breaking ground in Chicago, NARA had already relocated the physical records from the Obama administration to a temporary private facility. Shipping cost $300,000 and the rent in 2018 was $223,000 per month. The documents are expected to finally be relocated this year after which it is expected to save nearly $3 million.

Obama’s digital library model could become the standard going forward. Congress could also consider increasing the share of costs covered by the foundations of future former presidents for physical libraries. While presidential libraries serve an important role in preserving history, they are often criticized for lacking objectivity, functioning more as glorified shrines that celebrate their presidents rather than offering critical and balanced perspectives on their administrations. In addition, greater transparency from NARA on the costs per library and facility could help highlight problem areas for potential cost savings going forward.

share of costs covered by the foundations of future former presidents for physical libraries. While presidential libraries serve an important role in preserving history, they are often criticized for lacking objectivity, functioning more as glorified shrines that celebrate their presidents rather than offering critical and balanced perspectives on their administrations. In addition, greater transparency from NARA on the costs per library and facility could help highlight problem areas for potential cost savings going forward.

Conclusion

As the presidential library system grows with each administration, the challenges of preserving and maintaining these archives continue to strain resources.The Obama Presidential Library’s fully digital model offers a promising path forward, balancing accessibility with fiscal responsibility. By adopting similar approaches, increasing the financial contributions required from private foundations, and improving cost transparency, Congress and NARA can ensure that the system remains sustainable. If taxpayers are to shoulder the financial burden, implementing reforms now will safeguard both the integrity of the archives and the public’s trust in their stewardship.