Key Takeaways

- The average 1040 filer now faces $290 in out-of-pocket costs and spends 13 hours preparing a return. The compliance burden for Form 1040 for individual income taxes reached $144 billion, an all-time high, even as the number of expected filers declined.

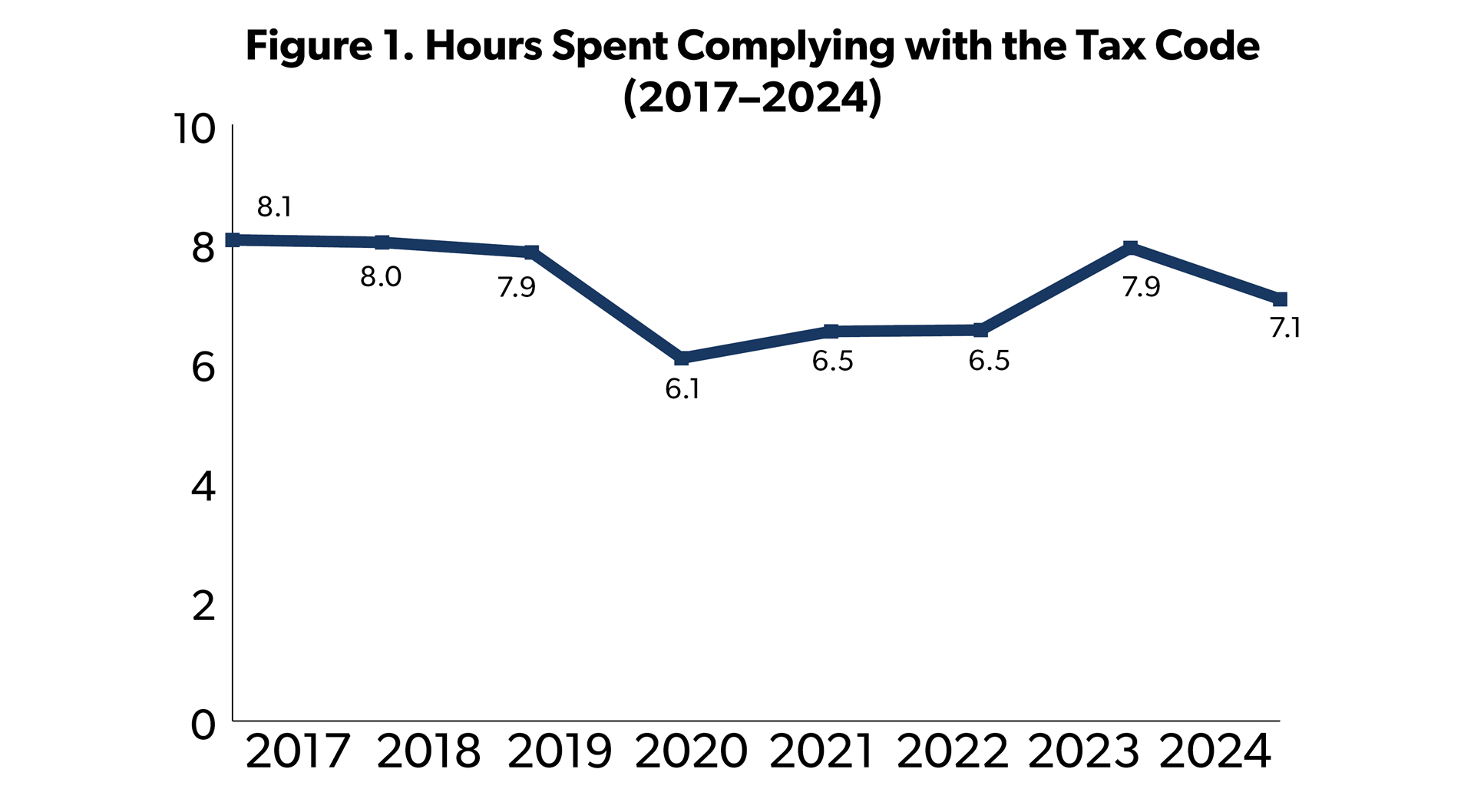

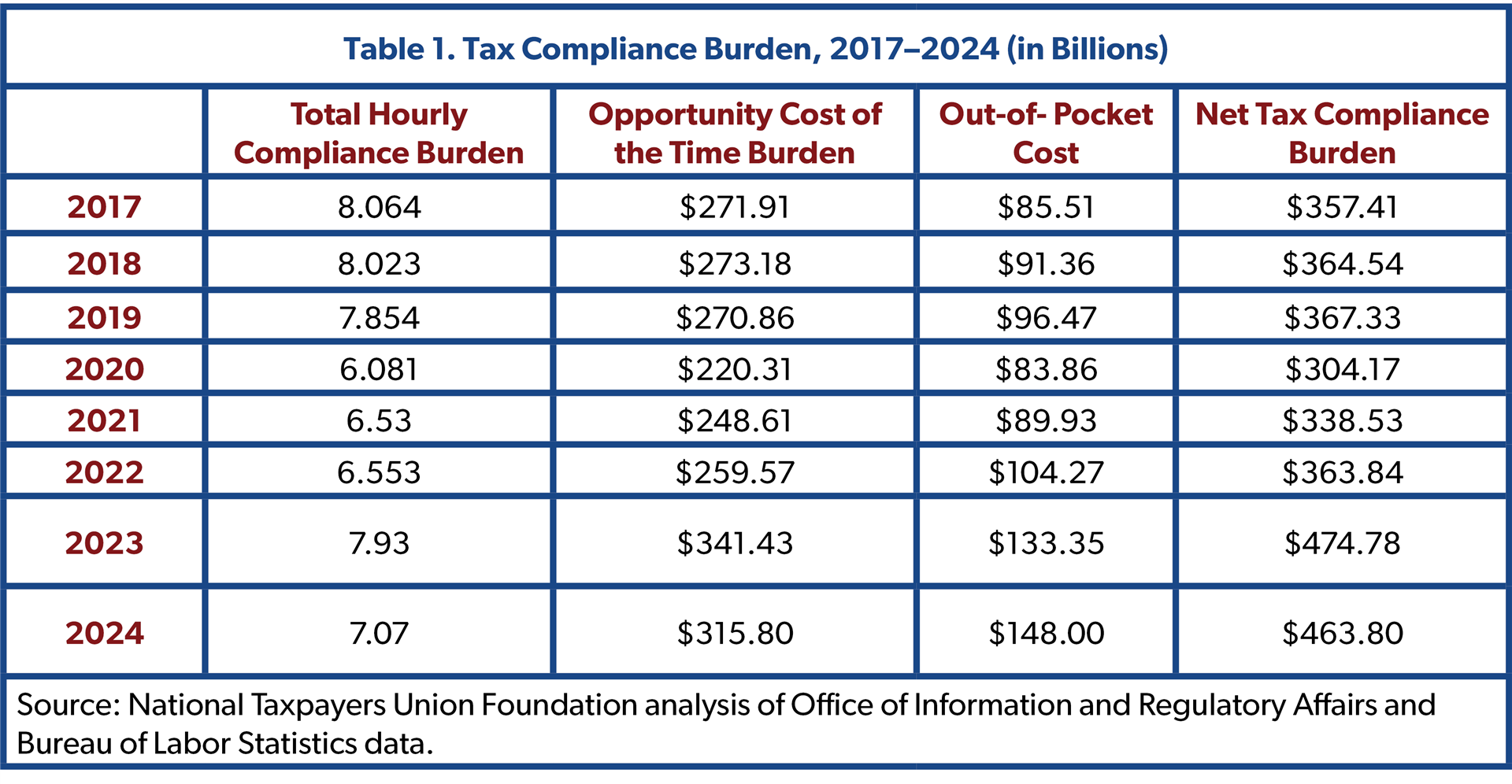

- Taxpayers will spend an estimated 7.1 billion hours complying with the tax code for Tax Year 2024—equivalent to $316 billion in lost productivity based on private sector labor costs.

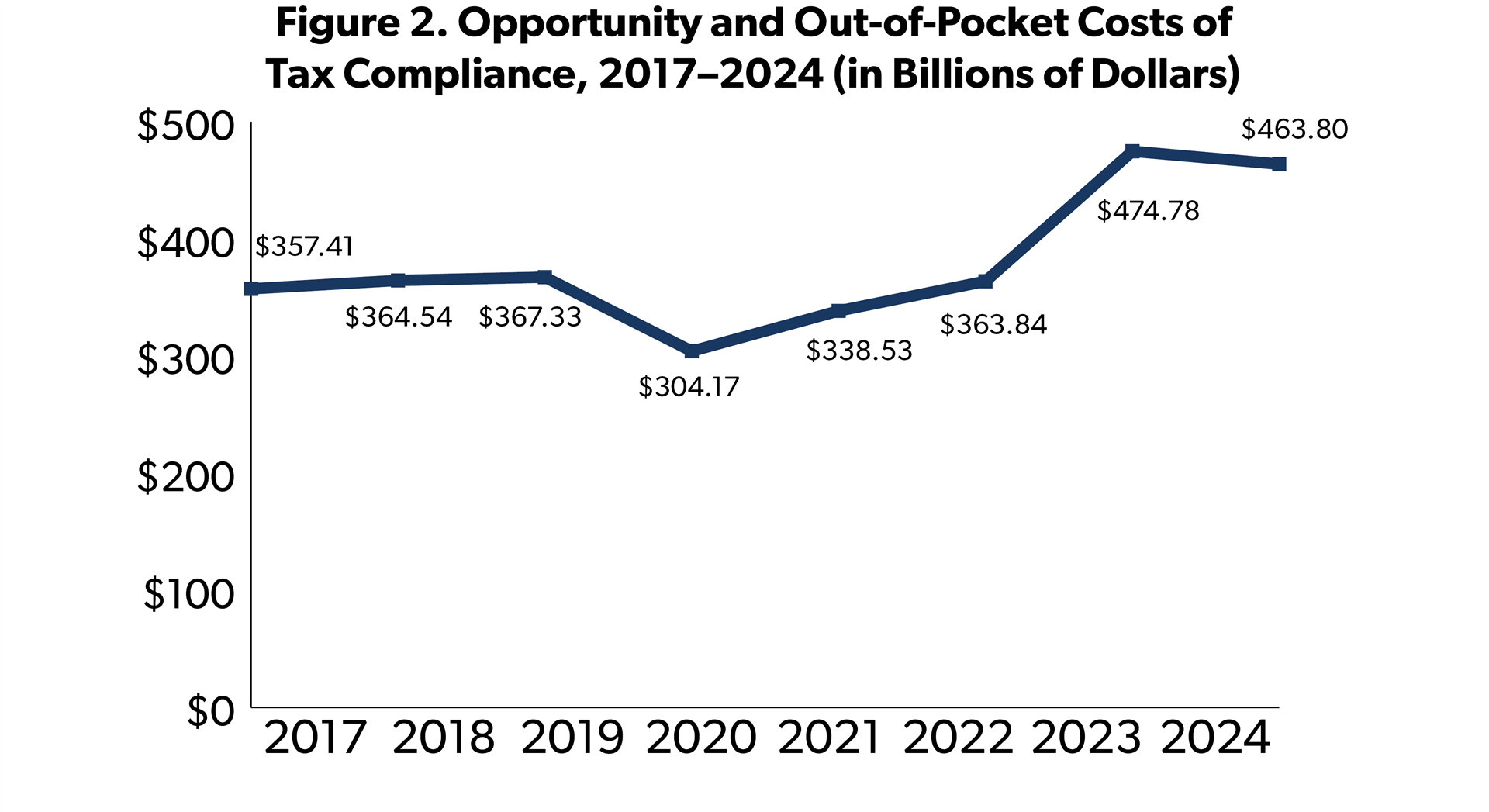

- Americans will face at least $148 billion in out-of-pocket expenses for filing, including tax software and professional services—bringing the total compliance burden to $464 billion, just shy of last year’s record.

- The total time burden dropped by 11% compared to the previous tax season, but this was due primarily to IRS modeling changes, not simplification. Most taxpayers will not experience any real reduction in complexity.

- The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act freed up hundreds of millions of hours once spent on tax filing, but, with key provisions set to expire after 2025, including the increased standard deduction, taxpayers could face longer forms and higher costs unless Congress acts.

- Real tax reform means more than just lower rates—it should also reduce paperwork, improve IRS service, and cut the cost and time taxpayers spend just to stay compliant. Ideally, the average taxpayer should be able to fill out a1040 Form in two to three hours.

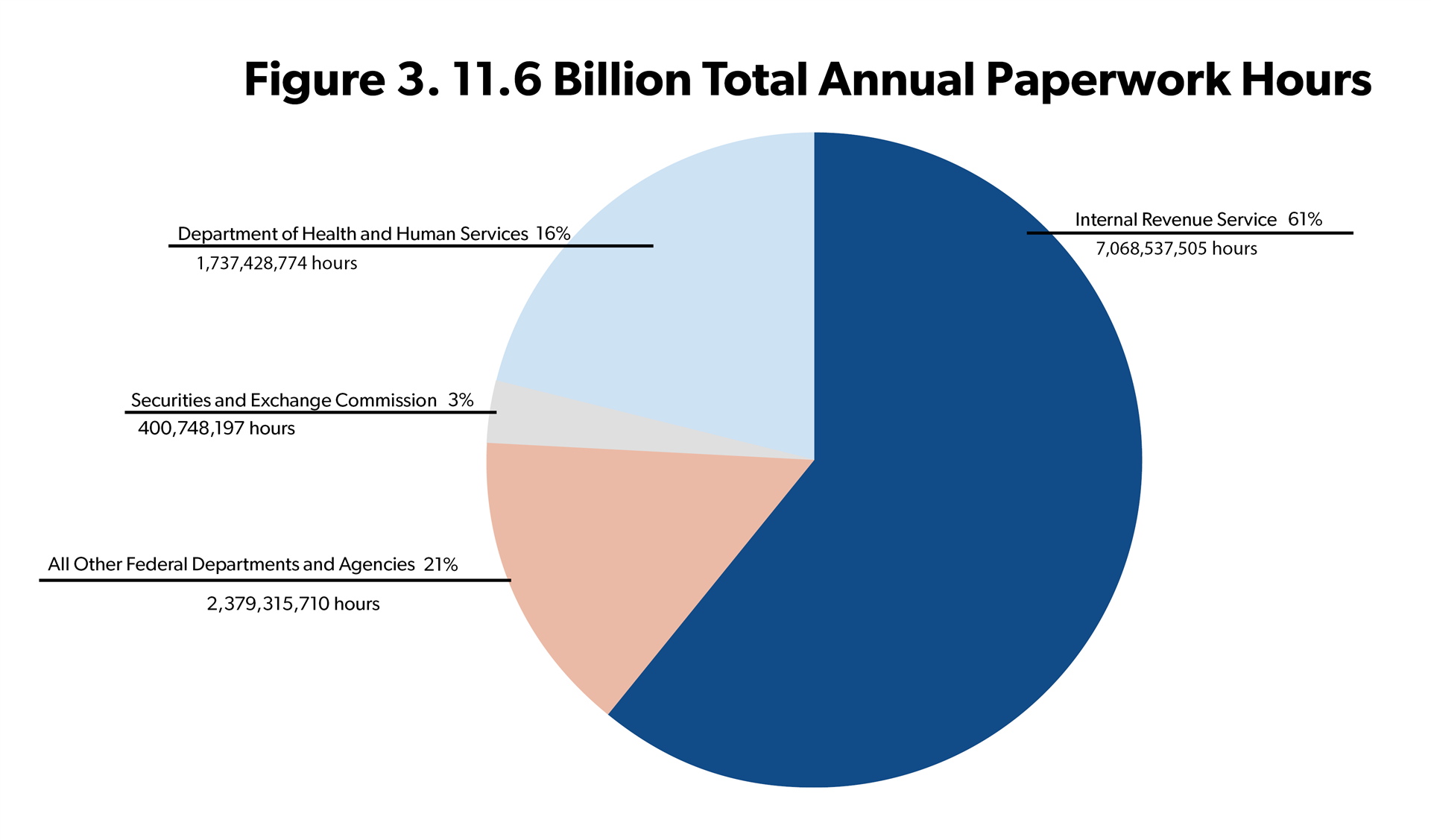

Americans will spend an estimated 7.1 billion hours preparing their 2024 taxes this filing season—a hidden tax on productivity that costs the economy $316 billion in lost time. On top of that, taxpayers face at least $148 billion in out-of-pocket costs for tax prep software and professional services, bringing the total compliance burden to a staggering $464 billion. IRS-related compliance makes up 61% of all paperwork burdens placed on Americans by the federal government.

Compared to last year, the dollar cost is about even ($464 billion this year vs. $475 billion last year). Much of the increase is due to higher labor and service costs. While the hourly burden is significantly lower (7.1 billion this year vs. 7.9 billion last year) most of the reported reduction in hours is due to IRS modeling changes—not actual simplification, so most taxpayers will see little difference in their experience. The hours burden remains below the 8 billion hours annually spent prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

As Congress engages in major tax debates this year, lawmakers should focus on reducing the tax compliance burden through real reform. Taxpayers deserve a simpler, more efficient system—and a government that values their time as much as their tax dollars.

The Tax Code’s Complexity and Compliance Burden

Time and Cost Burdens Filing for Tax Day 2025

Each year, NTUF analyzes data and documentation that the IRS is required by law to submit to the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) to track paperwork burdens. For the 2024 tax year, Americans spent an astonishing 7.1 billion hours complying with the tax code—handling everything from recordkeeping and researching the rules to completing forms and submitting them to the IRS. All of that adds up to a tremendous drain on time and productivity.

To better understand the real-world impact of that burden, NTUF also estimates its economic cost using private sector labor rates. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. non-federal civilian employers were paid an average of $44.67 per hour in 2024—including wages, salaries, and benefits. That’s a 3.6% increase from 2023, driven in part by persistent inflation. When applied to the 7.1 billion hours spent on tax compliance, the opportunity cost totals a staggering $316 billion—a hidden tax on time that Americans never get back.

And that’s just the value of time. On top of that, taxpayers shoulder significant out-of-pocket costs—estimated at $148 billion—for tax software, professional preparation services, and other filing-related expenses like printing and copying. It’s worth noting that this figure is based on an incomplete estimate from the IRS (more on that below), so the true amount could be even higher.

In total, the economic burden imposed by tax code compliance reaches $464 billion.

Meanwhile, the cumulative 7.1 billion hours spent in preparation for Tax Day would stretch out to over 806,910 years. That’s longer than all of recorded human history—by a factor of 100.

How Tax Compliance Burdens Are Calculated

Under the Paperwork Reduction Act, federal agencies must estimate how much time and money the public will spend completing each form they issue. These estimates—along with the forms themselves—must be approved by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) before being put into use.

While most federal paperwork is reviewed every three years, tax-related forms face more frequent, often annual, scrutiny. Once approved, the estimated burdens are published by OMB’s OIRA, along with detailed supporting statements from the issuing agency.

NTUF reviews and compiles the burden estimates from the IRS’s information collections each year. Many of these collections cover multiple forms and schedules, reflecting the full scope of tax compliance tasks.

Tax Forms Dominate the Government-Wide Paperwork Burden

It’s no surprise that IRS forms make up the bulk of the paperwork burden imposed by the federal government. Across all departments, agencies, and commissions, there are currently 10,801 active information collections—212 more than last year. While IRS forms represent just 4% of that total, they account for a staggering 61% of the government-wide 11.6 billion-hour paperwork burden.

Trailing far behind is the Department of Health and Human Services, responsible for 1.7 billion hours, followed by the Securities and Exchange Commission in third place with 401 million hours.

Comparing the Burden over the Recent Past

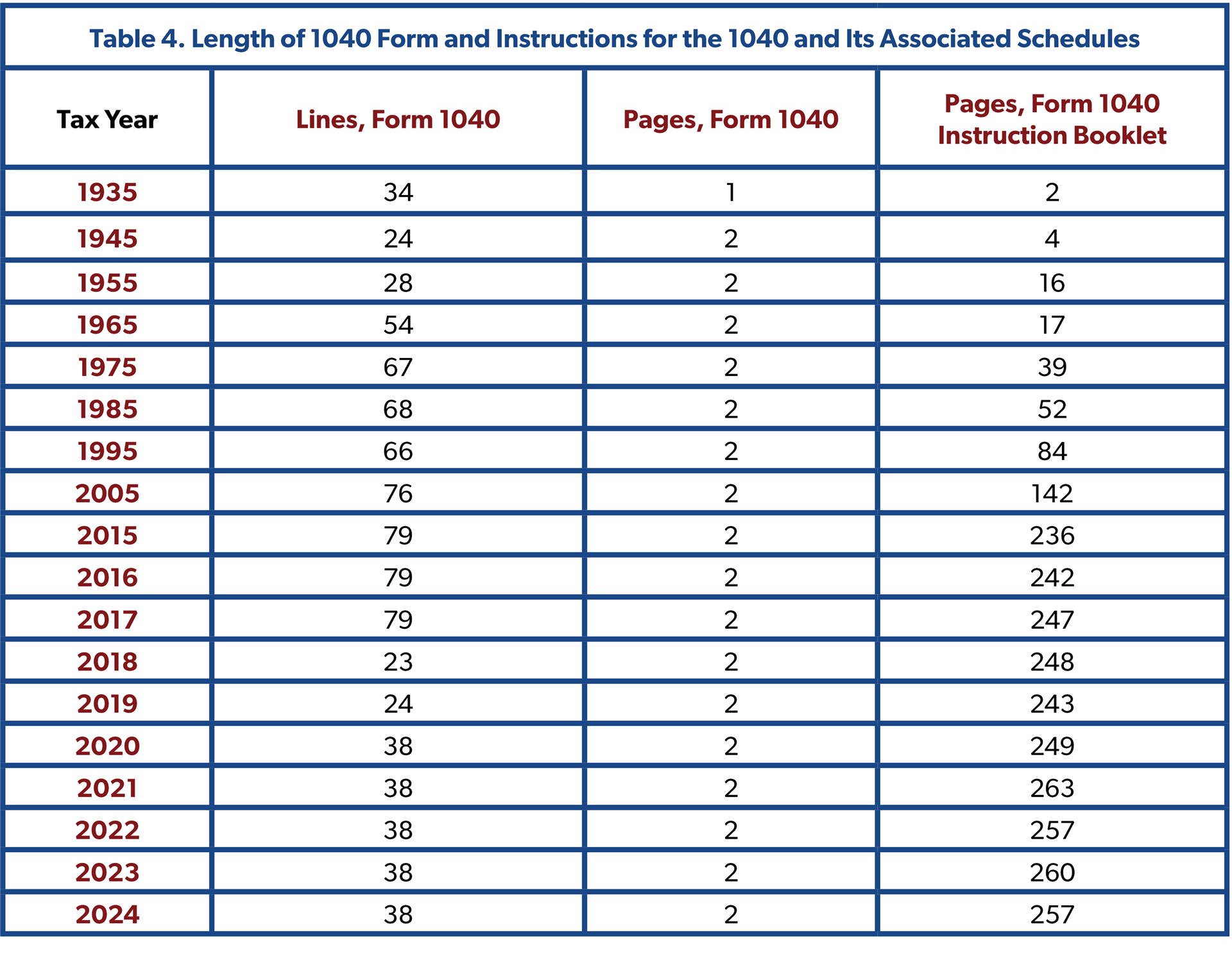

The total time Americans spend on tax compliance peaked in 2017 at just over 8 billion hours. The burden eased over the next several years, thanks in large part to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which took effect in 2018. Key reforms—like increasing the standard deduction, trimming the number of filers subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax, and simplifying Form 1040—helped reduce paperwork.

A sharp drop in 2020 reflected a long-delayed IRS methodology update that corrected overestimated business compliance hours. This change had been in the works for years, but the IRS held off until after the TCJA’s effects could be measured.

Although the hourly burden rose in 2023, much of the variation in recent years stems from methodological revisions to IRS data collections. Notably, had two major information collections remained unchanged in 2022, the time burden would have been higher—6.61 billion hours instead of the reported 6.55 billion.

Explaining the Changes in the IRS Information Collection

While the reported hourly burden for 2024 shows a significant decline from the previous year, this is largely due to technical changes in how the IRS estimates time burdens, not from any major improvement in tax code simplicity. For most taxpayers, compliance burdens remain as high as ever.

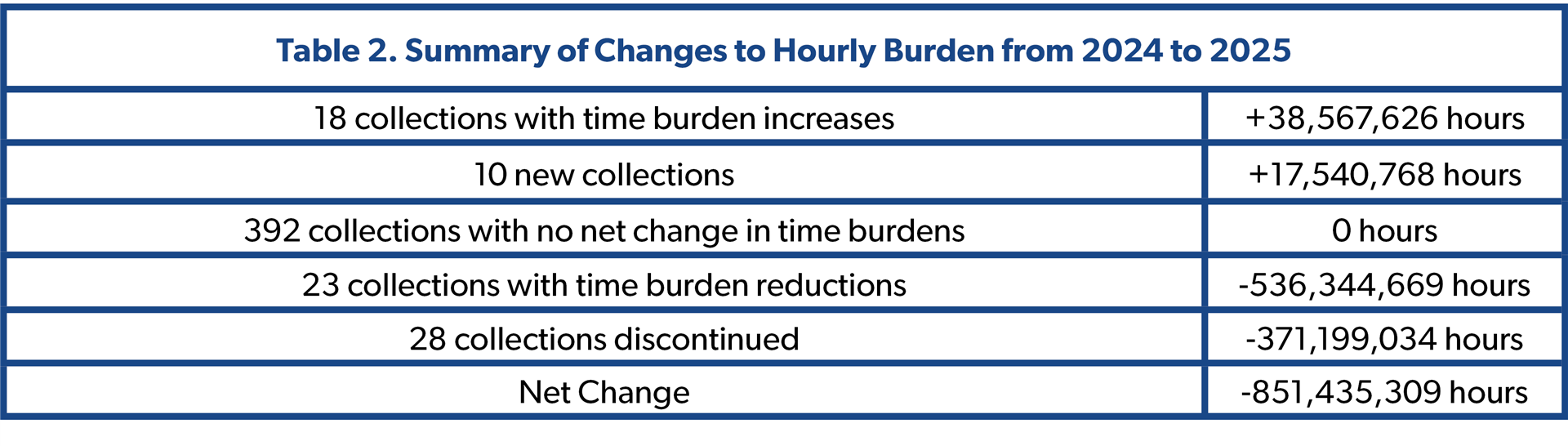

Table 2 summarizes changes in the IRS’s tax time burden estimates from April 2024 to April 2025. Of the 446 active collections, 392 (88% of the inventory) were renewed with no change in their estimated time burdens.

18 collections had increased burden estimates, adding 38.6 million hours. The largest increases occurred in:

Business Income Tax Returns (+15.1 million hours)

Employer’s Quarterly Federal Tax Return (+14 million hours)

There were 10 new information collections, contributing 17.5 million additional hours. Most of this came from a 2024 regulatory change implementing an Affordable Care Act provision on health coverage transparency, which added 14.3 million hours to the burden estimate.

Meanwhile, 23 collections saw reduced burden estimates, lowering the total by 536.3 million hours. These reductions were largely driven by changes in methodology, not by legislative or administrative reforms.

The most significant drop came from a one-time adjustment to the burden estimate for estate and trust tax returns, following the IRS’s switch from the outdated Arthur D. Little (ADL) model to the more modern Taxpayer Burden Model (TBM). The IRS has noted that the TBM:

. . . establishes econometric relationships between tax return characteristics from IRS administrative data and the time and out-of-pocket costs reported by those taxpayers via survey data. Most importantly, it takes a taxpayer-centric view of tax compliance burden, considering taxpayers’ actual prefiling and filing experience. It recognizes the need to survey taxpayers periodically to ensure that the model can be updated to properly represent the current tax compliance experience.

This shift resulted in a dramatic reduction in estimated responses (down 8 million) and a time burden drop from 357 million hours to 31.9 million hours. Again, this reduction reflects a change in modeling assumptions, not a simplification of the filing process.

The second-largest reduction was for individual income tax returns. The IRS revised its estimated number of responses from 171.8 million to 168.8 million, resulting in a net reduction of 120 million hours. As with the estate and trust forms, this decrease did not reflect actual taxpayer experience, but rather adjustments to the underlying assumptions.

Table 2 also shows that the IRS also discontinued 28 collections, which shaved off an additional 371.2 million hours from the total burden. However, NTUF determined that at least 21 of the forms are still in use—their time burdens have simply been reclassified under other existing information collections.

The most significant discontinued collection is for Form 8995 and Form 8995-A, used to claim the Section 199A Deduction for Qualified Business Income enacted in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Previously, the IRS estimated that it would receive 41.4 million responses for this, with total annual time burdens of 336 million hours. In response to an NTUF inquiry, an IRS official confirmed that these burden estimates were redistributed across other collections—primarily the newly adjusted estate and trust forms, which, as noted, underwent significant reductions due to the modeling switch. However, given that the Congressional Research Service notes that Section 199A is a “complicated tax provision,” it remains to be seen whether taxpayer experience aligns with the IRS’s reduced compliance burden estimates.

The Complexity Burden of Sections of the Tax Code

Overview of Tax Forms

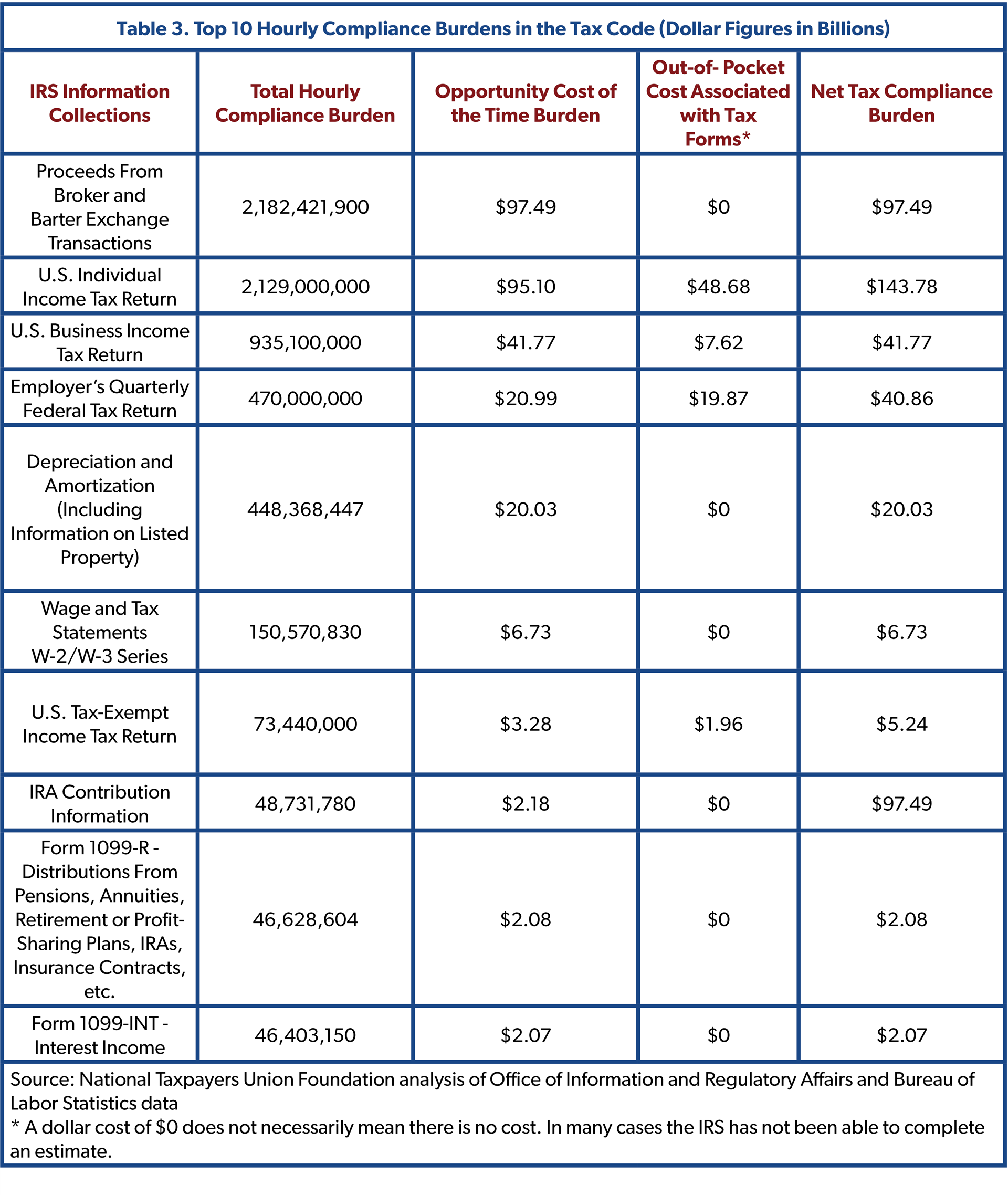

Table 3 highlights the ten most time-consuming IRS information collections based on the hourly compliance burden. As in prior years, individual and business income tax returns continue to dominate the list, but the single most burdensome collection is now “Proceeds from Broker and Barter Exchange Transactions,” primarily reported on Form 1099-B.

With an estimated 2.18 billion hours required to comply, Form 1099-B alone surpasses the entire burden of individual income tax returns. The IRS anticipates receiving 4.36 billion submissions of this form—nearly 13 for every person in the United States.

This information collection vastly expanded due to digital asset taxation provisions enacted in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act. Congress recently passed a joint resolution for congressional disapproval under the Congressional Review Act targeting the IRS’s regulations for digital asset reporting. It remains to be seen whether this will lead to a reduction in compliance burdens going forward.

Despite these staggering time burdens associated with Form 1099-B, the IRS still does not estimate any out-of-pocket costs associated with this collection, raising questions about whether the true burden is being fully captured. Across the IRS’s entire inventory, only 30 information collections include an associated out-of-pocket cost estimate—just five more than last year.

One notable improvement came with the IRS’s adoption of a new burden model for estate and trust returns, which now includes an estimated $5.5 billion in out-of-pocket costs. This translates to an average compliance cost of $1,791 per response, on top of the $37 billion tax bill in estate and gift tax liabilities projected for this year.

For many of the 412 collections that report no associated costs, this is likely because compliance is relatively simple—especially in cases like W-2 forms, which are often automated through payroll software. However, for more complex collections such as Form 1099-B, IRS supporting statements acknowledge that they are still developing a methodology to evaluate and report out-of-pocket compliance costs more accurately.

The Overall Individual Income Tax Compliance Burden

The part of the tax code most familiar to Americans is Form 1040, along with its associated schedules and instructions.

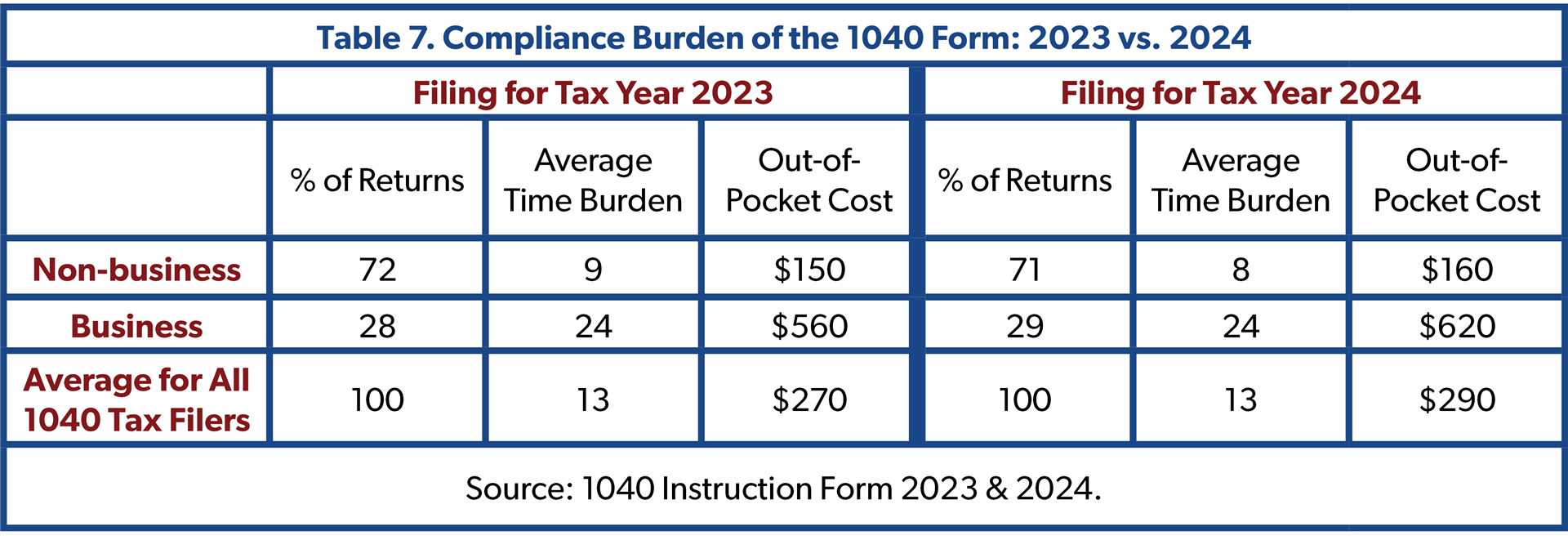

As shown in Table 5, the hourly compliance burden for the individual income tax declined in 2024 for the first time since 2019, largely due to a drop in the number of expected filers. However, the IRS’s estimates for out-of-pocket costs continue to rise, pushing the net compliance burden for individual filers to nearly $144 billion—a record high.

The IRS made some adjustments since last year reflecting policy changes and taxpayer behavior:

On net, the number of filers is expected to fall, which will lead to fewer time burdens overall.

Filers claiming the clean energy incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act will incur an additional aggregate 1 million hours and $26 million in out-of-pocket costs, and

Changes to the reporting threshold for Form 1099-K will cause confusion for many taxpayers; the IRS used a mid-point estimate that projects 1 million additional burden hours and $33 million in out-of-pocket costs.

Table 5 shows aggregate burden trends. Table 6 focuses on burden per filer, which is crucial for demonstrating how complexity affects individual taxpayers, regardless of how many people are filing.

The experience of different taxpayers can vary greatly from the average time burden calculated by the IRS. Individuals have much lower average time burdens (nine hours) than pass-through businesses (24 hours) that use the 1040 Form to file individual income taxes. On average, all 1040 filers faced a time burden of 13 hours, with average out-of-pocket costs increasing from $270 to $290.

Business Income Tax Compliance Burden

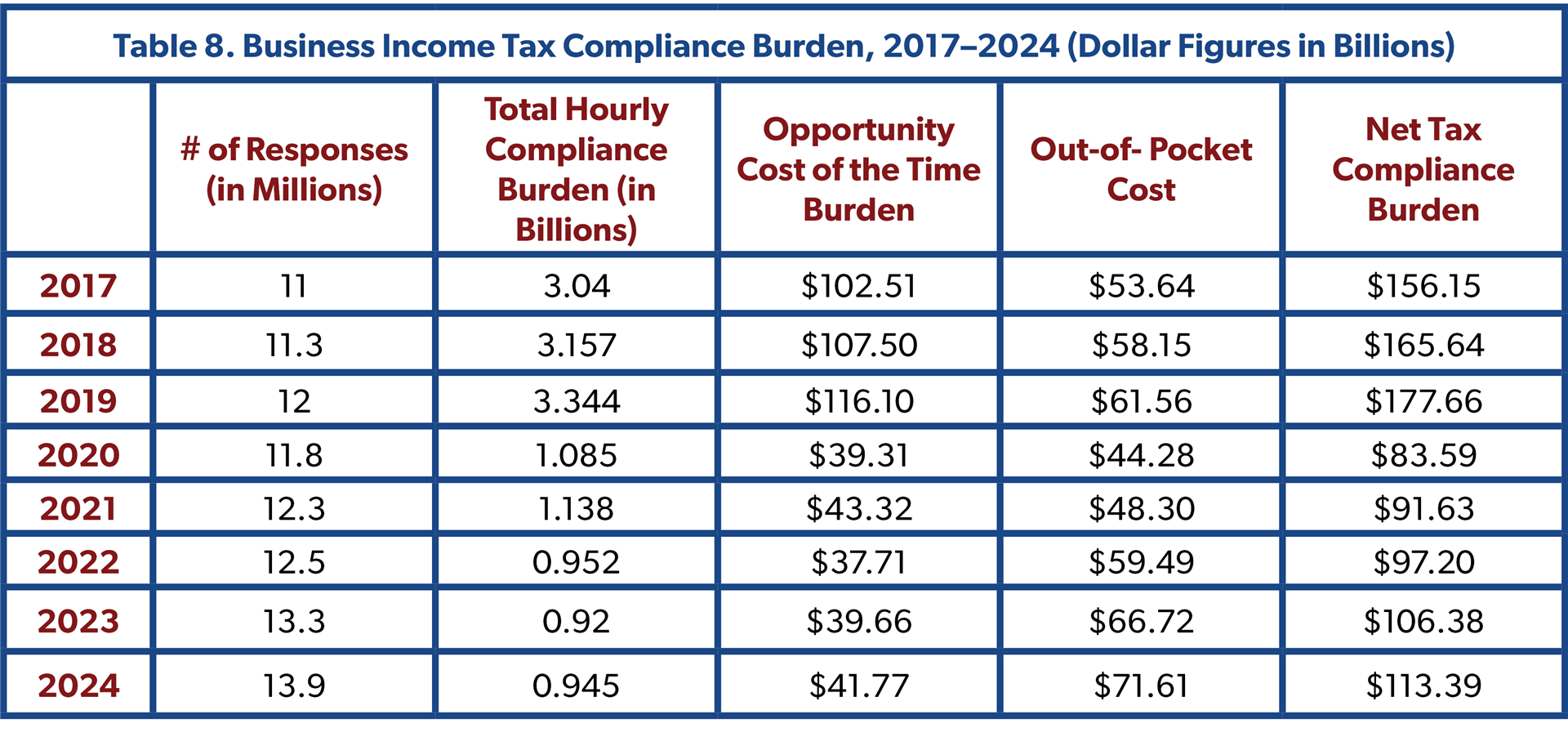

Corporations and certain partnerships are required to file Business Income Tax returns, and the overall burden for these filers remains substantial. The number of business tax return respondents is projected to increase in 2024 to 13.9 million, up from 13.3 million in 2023. Though the total hourly burden has decreased compared to pre-2020 levels—largely due to methodology changes—the net tax compliance burden continues to grow, rising from $106.4 billion in 2023 to a projected $113.4 billion in 2024. This reflects increases in both the opportunity cost of time and out-of-pocket costs, the latter of which has climbed by over 30% since 2020.

Elements of Complexity

Length of the Tax Code and Regulations

One of the key drivers of tax complexity is the sheer size and scope of the tax code itself: now standing at over 4 million words. When the income tax was first enacted in 1913, the tax code spanned just 27 pages. But within a few years—thanks to amendments, new regulations, and judicial rulings—the code had already risen to 400 pages.

Since then, complexity has only ballooned. Lawmakers frequently revise and expand the tax code, often with far-reaching consequences. While the extent of each change varies, frequent substantive revisions increase the administrative burden on the IRS, which must update forms, retrain staff, and educate taxpayers. These changes also create uncertainty and additional compliance hurdles for filers.

Between 2000 and 2024, Congress enacted an average of 369 tax code changes per year (see Figure 2). The pace has varied dramatically—from a high of 797 changes in 2010 to a low of just 3 changes in 2013. Notably, the pace of legislative tax changes slowed significantly in recent years, with just 15 changes in 2023 and 39 in 2024.

Comparing the length of the tax code over time is complicated by differences in formatting—such as layout, font, column width, and margins—which can significantly affect page counts. To ensure consistent year-to-year comparisons, NTUF uses a standardized method: the full text of the tax code is copied into Microsoft Word, and the word count tool is used to measure its length. While this method isn’t perfect—especially given the code’s numerous cross-references—it provides a consistent benchmark. This approach was also used by the Office of the Taxpayer Advocate, which estimated that in 2017, the tax code contained 4 million words. Following the passage of the TCJA, the number of words began to decline, reaching 3.96 million by 2020. Since then, it has steadily increased and now stands at 4,231,529.

To interpret and implement these statutes, the Department of the Treasury publishes regulations that span 22 volumes of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). The most recent complete edition, incorporating revisions through April 2024, includes 17,472 pages (including tables of contents and introductory text) and more than 12 million words—further illustrating the scale and complexity of federal tax administration.

Combined, the number of words in the tax code and the number of words in regulations is more than twice as high as it was in 1994.

Beyond the issuance of regulations, the IRS regularly provides guidance through notices, announcements, private letter rulings, and technical advice memorandums to address emerging issues. While some of these documents apply only to individual taxpayers and carry limited legal scope, others offer substantive interpretations of complex tax provisions. For individuals and businesses with complicated financial situations, staying on top of this growing body of informal guidance is essential to ensure full compliance with applicable laws and regulations.

However, the IRS has significantly increased the fees associated with certain types of pre-filing guidance—particularly private letter rulings—which may be deterring taxpayers from seeking advance clarification. As access to these tools becomes more expensive, the complexity of the system grows even more burdensome for those trying to get things right the first time.

Substandard Taxpayer Services

While the IRS has made some improvements in taxpayer services since the widespread government shutdowns of 2020, serious challenges persist—especially for taxpayers who seek help navigating complex filing questions.

Many taxpayers attempt to call the IRS for assistance, but it’s unclear how often they receive useful or even accurate information. As the Taxpayer Advocate Service (TAS) has pointed out, the IRS uses a flawed metric to track how many calls are answered. Specifically, the IRS calculates its Level of Service (LOS) by dividing the number of calls assisted by a live agent by the number of calls the phone system routed to a live agent. This means the denominator excludes the total volume of incoming calls—including those that were disconnected, abandoned, or rerouted to automated menus—making the LOS figure a poor measure of actual performance.

In its review, TAS found that only 32% of all incoming calls were answered by a live assistor. The rest were either transferred to automated responses or disconnected before reaching an agent. This raises serious concerns about whether taxpayers are actually getting the help they need.

Even if taxpayers successfully get through to a live assistor, they might still be out of luck. The IRS has classified large sections of the tax code as “out of scope” for telephone assistance. For these areas, the agent is only able to refer the taxpayer to information on the IRS website.

Last year, NTUF counted over 130 out-of-scope areas. However, the list, previously published on the IRS website, has since disappeared from public view, even though references to it remain on other pages outlining customer service procedures. The same restrictions apply to IRS tax preparation programs like Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) and Tax Counseling for the Elderly (TCE), which are also limited in the topics on which they’re allowed to assist. The list of areas with limited or out-of-scope topics is also currently unavailable.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) provided the IRS with a significant funding boost—but most of the remaining $57.8 billion is reserved for enforcement activities. While the IRA included $3.2 billion for taxpayer services, that funding is set to run out this year. Without additional flexibility to shift resources to taxpayer service, the IRS risks backsliding on the modest gains it has made in service quality. Congress should give the IRS Commissioner the authority to reallocate a portion of enforcement funds toward improving customer service, including call center staffing, expanded assistance for out-of-scope issues, and better public-facing guidance.

Taxpayers may face additional uncertainty during the current filing season due to efforts to freeze funding for VITA and TCE, as well as internal personnel policy changes at the IRS that have placed many IT and taxpayer service employees on paid leave. These disruptions could extend beyond return filing to post-filing actions, including appeals, as staffing reductions have also affected IRS units responsible for handling taxpayer disputes.

The Inflation Reduction Act also provided $4.8 billion for business systems modernization, but these funds are expected to be exhausted by FY 2026—even as the IRS continues to rely on woefully outdated and disconnected technology systems. For example, the agency still operates 60 separate legacy case management systems, meaning an IRS agent answering a taxpayer’s call may not have access to that taxpayer’s specific records or history. The IRS’s technological status quo remains unacceptable, with necessary next steps remaining unimplemented.

Despite decades of attempts and billions of dollars invested in technology upgrades, the IRS’s core processing system, known as the Individual Master File (IMF), remains based on 1960s-era assembly language—an increasingly obsolete foundation for a modern tax system.

Improving the IRS and the Tax Code

While the most recent decline in compliance burden hours is largely attributable to methodological changes, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 made significant strides in simplifying the tax code. The TCJA cut individual tax rates across the board, with most tax brackets seeing a reduced rate. All told, about 80% of Americans received a tax cut under the TCJA, with an average tax savings of over $2,100. Only about 5% of Americans received a tax increase as a result of the law.

In addition to reducing tax liabilities for roughly 80% of filers, the TCJA also cut down on the time and out-of-pocket costs associated with filing. One major simplification was the near doubling of the standard deduction from $6,500 to $12,000 for single filers and from $13,000 to $24,000 for married filers. Around 30 million Americans now see a dramatically simpler tax filing experience due to this change: in 2024, 150.3 million taxpayers (90.1%) took the standard deduction while 16.4 million taxpayers itemized; prior to the TCJA, 46.5 million taxpayers (30%) itemized.

If Congress fails to extend the TCJA’s expiring provisions, taxpayers will not only see smaller paychecks but also face longer, more complicated filing experiences. To avoid this double hit, lawmakers should ensure that future tax reforms—especially those paired with an extension of the TCJA—minimize added compliance burdens and unnecessary taxpayer headaches.

While Congress often relies on fiscal estimates from the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), lawmakers should also incorporate insights from IRS analysts who prepare taxpayer burden estimates. These estimates are critical for understanding how changes to the tax code impact everyday filers.

In 2023, the House Budget Committee began a series of hearings to examine CBO’s operations and explore improvements to its budgetary modeling and transparency. A similar oversight effort could be led by the House Ways and Means Committee or Senate Finance Committee to examine the IRS’s analytical division and its modeling methods. Representative Warren Davidson (R-OH) introduced the CBO Show Your Work Act to enhance transparency in CBO’s assumptions and methodologies. A similar proposal could be developed to require the IRS to increase transparency in its burden modeling, which could serve to improve the IRS in complying with its Paperwork Reduction Act obligations.

As noted earlier, despite recent progress, the IRS still has serious deficiencies in accounting for out-of-pocket costs in its burden estimates. A full accounting of these costs, and greater clarity around IRS models, could help lawmakers determine whether specific forms or filing requirements impose undue burdens on taxpayers.

The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs should also work with the IRS to distinguish between forms or information collections with truly zero out-of-pocket cost and those where cost estimates are incomplete or unavailable. This would provide a clearer picture of which parts of the tax code are in most need of simplification.

Conclusion

Beyond forms and models, improved taxpayer services and education can also play a pivotal role in easing compliance challenges and encouraging accurate filing. While most of the Inflation Reduction Act’s IRS funding was reserved for enforcement, there are more taxpayer-friendly ways to promote compliance—especially given the IRS’s historical tendency toward heavy-handed enforcement.

With persistent taxpayer service backlogs, outdated technology systems, and recent reports of layoffs and a looming wave of retirements, the IRS continues to struggle to meet its core responsibilities. These challenges have been compounded by the complexity of recent tax code changes and the lingering effects of pandemic-era disruptions.

Policymakers should consider:

Reallocating Inflation Reduction Act funding toward taxpayer service. Putting enforcement funding toward improving taxpayer services, simplifying IRS communications and forms, and upgrading legacy IT systems like the Individual Master File would help taxpayers understand their obligations and file more efficiently, going a long way toward closing the tax gap and rebuilding trust in tax administration.

Scheduling hearings for a new IRS Commissioner. The IRS has been operating under an acting director since January. President Donald Trump nominated former Representative Billy Long (R-MO) on January 20, 2025, but a hearing to consider his nomination has not been scheduled yet. NTUF also has suggested ten reforms that the administration and a new commissioner should implement that will ensure the IRS does not fail taxpayers.

Expediting the nomination of a permanent Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA). TIGTA has been operating under an acting IG since January 2024. Having a Senate-confirmed IG is critical for maintaining strong oversight of the IRS. TIGTA plays a vital role in identifying waste, fraud, and abuse in tax administration.

Reconstituting and revitalizing the IRS Oversight Board. The IRS Oversight Board was created in the IRS Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998 with the purpose of bringing in outside experts to oversee the “administration, management, conduct, direction, and supervision” of IRS operations. It was specifically tasked with reviewing and approving the annual and long-range strategic plans of the IRS, including its mission and objectives. A reconstituted and revitalized IRS Oversight Board could play a critical role in guiding the agency toward improved service, smarter modernization, and more effective use of its resources.

Keeping the expanded standard deduction in new tax legislation and further reforms that simplify the tax code. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 doubled the standard deduction, wiping out most of the compliance burden for 30 million taxpayers. As Congress decides whether to extend the TCJA past 2025, that reform should be kept and expanded. With 25 states now having no income tax or a flat income tax, the template exists for Congress to remove carveouts, lower rates, and make tax filing for the average American simple enough to be done in an hour or two.

These administrative reforms could finally begin to address what remains the least-understood compliance burden of our tax system: the time and money taxpayers spend in undergoing audits, responding to notices, haggling in Tax Court, and other activities outside of filing forms, keeping records, and financial planning.

America’s system of tax laws and tax administration is at a crossroads in 2025, with major parts of the TCJA set to expire and new leadership coming to the IRS. Depending on which direction policymakers choose, the path ahead could lead to a tax system that is simpler and more transparent. Time, money, productivity, and our civil liberties are all at stake.