(pdf)

Introduction

Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in 2022, which included just under $80 billion in additional funding for the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) over a ten-year period, increasing its funding by over 50 percent.[1] Though approximately $21 billion was later rescinded, the IRS remains set to benefit from a significant boost to its funding over the next decade.

But while additional funding should expand the IRS’s capabilities, the IRA left things fairly open-ended as to how exactly the IRS should direct these new resources and what metrics it should be focusing on. In order to fill this gap and provide the IRS and policymakers with expert advice on reform and modernization while spending plans develop, the National Taxpayers Union Foundation (NTUF) launched its Taxpayers for IRS Transformation (Taxpayers FIRST) project.

At the core of the Taxpayers FIRST project is the convening of an advisory board made up of former IRS officials, academics, practitioners, accountants, and policy experts. These advisory board members have diverse views and backgrounds, but are united in the shared goal of ensuring that the taxpayer dollars entrusted to the IRS help make it more efficient, effective, and accountable.

Informed by the discussions of the Taxpayers FIRST Advisory Board, NTUF is publishing four reports covering areas IRA funding was meant to address. The ideas in these papers do not necessarily reflect the specific views of any single member; rather, they are synthesized views after critical debate, discussion, and review by the Advisory Board.

This report represents the third installment of this series. It focuses on continuing efforts to modernize the IRS, briefly outlining the woefully outdated technology and processes and discussing how funds provided under the IRA can best be used to address those problems.

A Recent History of IRS Modernization Efforts

The current effort to modernize the IRS dates back to the 1970s, when policymakers started expressing new concerns about the effectiveness, fairness, and efficiency of federal tax administration and the quality of service provided to taxpayers. An early milestone in this effort was the passage of the IRS Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998 (RRA 98), which reorganized the IRS into four major operating divisions based on the type of taxpayer, rather than by type of tax. In addition, it updated the roles and functions of key positions within the IRS, including the Commissioner and the National Taxpayer Advocate. It also included provisions to enhance taxpayer rights and protections to prevent abuses.

The law also included mandates for the modernization of the IRS’s technology, systems, and processes, designed to improve its overall efficiency.[2] For one example, in 1998, 23 percent of individual returns were filed electronically. RRA 98 directed the IRS to increase this rate to 80 percent by 2007.

While RRA 98 marked a significant shift in the IRS approach by placing a stronger emphasis on taxpayer rights and services, subsequent modernization efforts have been largely slow-going. Over the past 15 years, Congress has passed several laws that included provisions to modernize certain tasks and services performed by the IRS.

Leading up to the funding for modernization included in IRA, such laws include:

- The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 – Contained provisions for modernizing IRS technology and infrastructure, largely to improve the ability to administer tax credits established in the Act.[3]

- The Taxpayer First Act of 2019 – First major legislative effort to reform the IRS since 1998. It focused on modernizing the IRS’s technology, enhancing security, and improving taxpayer services.[4]

- The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act of 2020 – Primarily a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, but it included funding and provisions to allow the IRS to rapidly adapt systems to implement new tax provisions and stimulus payments.[5]

- Annual Appropriations – Various appropriations acts have included funding and directives for the IRS to continue updating its technology and improving services.

The Unacceptable Status Quo

The federal government spends about $90 billion – roughly three times the annual budget of the Justice Department – on information technology (IT) across non-Defense agencies.[6] Despite the substantial taxpayer investment,[7] the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has found that, over the years, federal modernization efforts “often resulted in multimillion-dollar cost overruns and years-long schedule delays, with questionable mission-related achievements.”[8]

These broader modernization problems are intensified at the IRS given the age of its central data management platforms, the dozens and dozens of case management systems it uses, and the sheer volume of the data it collects. Major modernization challenges at the IRS include: 1) resource and structural limitations; 2) the continued use of outdated technology and processing systems; and 3) staffing challenges.

Resource & Structural Challenges. Advocates of IRS modernization often point to historic funding challenges as the major impediment to their efforts. Over the years, the IRS’s budget has been subject to political scrutiny with elected officials often looking to reduce its funding to lower costs or limit its enforcement reach. Since the early 2010s, the Service has experienced a series of budget cuts – its budget was nearly 20 percent lower in FY2020 than in FY2010 after adjusting for inflation.[9] At the same time, Congress has continually expanded social programs under the IRS’s purview – like the earned income and child tax credits and tax subsidies for higher education – while it also administers a tax code that has grown more complex. This shortage of resources has been routinely cited to explain reduced staffing levels, limits on enforcement, and the failure to update the IRS’s technology and processing systems.

However, while concerns about funding are legitimate, the IRS operates under a structure that can make any IRS-wide changes extremely difficult.[10] Therefore, that a major increase in funding would immediately jumpstart the IRS’s modernization efforts is not a given. That hypothesis is currently undergoing testing thanks to the IRA.

Outdated Technology. According to a 2023 GAO assessment, the IRS relies on outdated legacy technology to perform a wide range of essential operations. Specifically, GAO found that about 33 percent of the applications, 23 percent of the software instances in use, and eight of hardware assets were outdated. This included outdated applications ranging from 25 to 64 years old, along with software that was up to 15 versions behind the current version. As the IRS has readily acknowledged, the use of such legacy assets contributes to security risks, unmet mission needs, staffing issues, and higher costs.[11]

One obvious example of a woefully outdated – but still mission critical – IRS system is the Individual Master File (IMF), which is used to store and process all individual tax data, including names, addresses, social security numbers, credits, and deductions. Put simply, the IMF is the IRS’s most essential tax-processing application, containing data for about a billion taxpayers, both living and dead. But the application is more than 60 years old, making it the oldest computer system still in use by the federal government. It uses COBOL, an Eisenhower-era programming language that is now mainly used to maintain legacy systems.[12] IRS officials have referred to the IMF as “antiquated,”[13] while the GAO recently labeled it “archaic.”[14]

The precarious nature of the IMF system isn’t merely theoretical: the database experienced a failure on Tax Day 2018, disrupting virtually all IRS services – including the receipt of electronic tax payments – on the busiest day of the year. The crash was not the result of a cyberattack or malicious software. It happened because some newer pieces of hardware had a simple, but unforeseen, caching issue.[15]

Case management is another area where the IRS relies on outdated legacy systems. The IRS uses about 60 different case management systems to store taxpayer data.[16] Since these systems generally do not communicate with each other, agents speaking to a concerned taxpayer may have to search various systems to find the taxpayer’s information, or even transfer the call to another agent. The IRS has attempted to modernize and consolidate these legacy systems by deploying the new Enterprise Case Management (ECM) system, but the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) has found that the ECM does not meet cloud security standards.[17]

Outdated technology has consequences beyond inefficiency, as these systems serve as a data security vulnerability. The IRS collects a vast amount of taxpayer information including income, Social Security numbers, residency, and more. GAO has found that the IRS remains susceptible to security breaches through unauthorized access by employees and contractors and cyberthreats.[18] These concerns have been amplified by two recent leaks of taxpayer information where the IRS accidentally publicized private information and where taxpayer information was leaked by a private contractor to ProPublica.[19]

Antiquated Processing Systems. In addition to its obsolete IT, the IRS faces challenges with outdated and inefficient processing methods. Most notably, the Service continues to rely on paper-based processing for many tax returns and submitted forms. The National Taxpayer Advocate’s FY2023 report to Congress referred to paper processing as “the IRS’s kryptonite,”[20] resulting in slower processing times and a higher likelihood of error, all of which means higher costs to taxpayers and poorer customer service at the IRS.

In fall 2023, two years after the large funding boost for tax modernization in the Inflation Reduction Act was approved, TIGTA reported on some of the challenges the IRS has faced in transitioning to electronic records. According to the report, a substantial majority of taxpayers – almost 94 percent of individuals and just over two-thirds of businesses – file their returns electronically. Yet, a considerable number of returns – over 33 million – are still filed on paper. Despite the IRS’s efforts to digitize more of its records, it has failed to meet administration-wide benchmarks for electronic recordkeeping.[21]

TIGTA’s report highlighted several obstacles slowing the IRS’s efforts to shift toward digital records. Among these challenges are technological issues, including extremely limited access to the latest document-scanning technologies and inconsistent scanning systems and capabilities across the IRS. To address this, the IRS has recently announced its Paperless Processing Initiative (PPI) that aims to digitize all returns filed on paper by the 2025 tax filing season.[22]

Other hurdles in the IRS’s transition stem from a lack of cohesive strategy or planning. TIGTA pointed out that the IRS lacked a single, Service-wide digitization strategy. The strategies that were in place were either not up to date or no longer reflected administration priorities. Moreover, the IRS’s ongoing pilot programs designed to test potential approaches were limited in scope. As a result, TIGTA concluded that any large-scale implementation of any of the tested strategies was still years away.

Ongoing Staffing Issues. The IRS also faces unique challenges when it comes to recruiting, hiring, and training new employees. Many of these problems are the result of an aging IRS workforce – nearly two-thirds of IRS employees will be eligible for retirement over the next six years. And, according to recent reports, an unexpectedly large number of employees are resigning voluntarily.[23] Much of this can likely be attributed to the historic scarcity of resources at the IRS. For example, from 2011 until 2018 the IRS implemented a hiring freeze in part due to resource limitations.[24] But at least part of the problem stems from the organization’s use of outdated tech. Very few potential candidates for programming positions have the necessary knowledge or training to work with the obsolete programming languages used in several major IRS applications. Still other candidates simply have no desire to work with an entity that struggles to implement even basic information technology that is considered to be standard at most private-sector and many public-sector organizations. This connection between the IRS’s outdated tech and its recruiting struggles has been acknowledged by many auditors and observers in recent years.[25]

The Inflation Reduction Act

Congress ostensibly sought to address some of these modernization challenges with passage of the IRA. Among other things, this legislation provided a monumental increase in funding for the IRS – roughly $80 billion over ten years. This infusion of resources represented the largest one-time taxpayer investment in the history of the IRS. Yet the statute was primarily focused on increasing IRS enforcement activities in order to boost revenue collection and offset other spending. Over half – almost $46 billion – of the new IRS funds in the IRA were earmarked for tax enforcement. Much smaller amounts were allocated toward bolstering taxpayer services, updating existing IT, and improving operations.[26]

After passage of the IRA, a fierce debate over the increased IRS funding continued throughout much of 2022 and 2023. Ultimately, Congress and the White House agreed to rescind about a quarter of the funds as part of a compromise to raise the federal debt limit. Specifically, a debt-limit bill – the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 – clawed back $1.4 billion in unspent enforcement funds for 2023. In addition, the administration and congressional leaders agreed to reduce future IRS appropriations by $20 billion. Despite this setback, the Biden administration has said reduction of funds would not affect the IRS’s near-term modernization plans. And, as of January 2024, the IRS had not yet decided which spending categories would be impacted by the $20 billion rescission.[27]

Recent comments from the current IRS Commissioner suggest that the IRA’s modernization funds may be targeted for redirection in light of funding concerns as appropriations fall short of IRS annual budget requests. In a memorandum released in April 2023, the Commissioner notes that reductions in base funding “will require IRA funding to be shifted to general operations.”[28] Nearly a year later, during his February 2024 appearance in front of the U.S. House of Representatives Ways and Means Committee, the Commissioner stated that an insufficient base budget means that the IRS must borrow from the modernization fund to “keep the lights on.”[29] Of note, the IRA also included $25.3 billion for operations support and routine costs.

Influx and Allocation of Added Funding. The massive influx of new IRS funds, coupled with the disproportionate focus on enforcement activities, has drawn the ire of the IRA’s critics as well as long-time observers of past reform efforts. While some criticism has been hyperbolic – painting pictures of an “army of 87,000 IRS agents” sent to terrorize American taxpayers – others have been more measured.[30] For example, the National Taxpayers Union argued that the $80 billion for the IRS was “too much funding for a beleaguered agency delivered too fast.”[31] Indeed, given the IRS’s documented inability to bring its IT and administration processes into the 21st Century, many observers would find it reasonable for taxpayers to expect robust oversight of any major increase in IRS spending.

In a typical year, about 45 percent of the IRS’s discretionary budget is dedicated to enforcement. More than 57 percent of the IRA’s additional funding was sent in that direction. In contrast, the law directed only about 4 percent of the increased spending toward taxpayer services, which typically consumes about a quarter of the IRS’s annual budget.[32] The likely explanation for this discrepancy is that the IRA’s authors were more focused on hitting revenue targets than addressing the many ongoing technology and service deficiencies at the IRS.

Among others, National Taxpayer Advocate Erin Collins has called for a reallocation of funds from enforcement to other areas of need. For example, in March 2023 Collins called for reallocating IRA funds from enforcement to modernization and taxpayer services, arguing that doing so would ultimately reduce the need for additional enforcement:

“For anyone following tax administration in recent years, it’s a no-brainer that the areas that require improvement most urgently are taxpayer service and technology. And if the IRS would provide timely and clear guidance, more transparency, and more front-end services in a proactive manner, it could reduce back-end enforcement needs. Successful tax administration requires taxpayers to voluntarily file, self-assess, and pay the taxes due under our nation’s tax laws. Successful tax administration also requires the IRS to provide congressionally authorized benefits and credits quickly and efficiently.”

Given the partial rescission of IRA funds, the IRS will almost certainly have to consider these questions in the near future. However, the IRS has recently produced reports touting the projected impact of its newly enhanced enforcement efforts.[33]

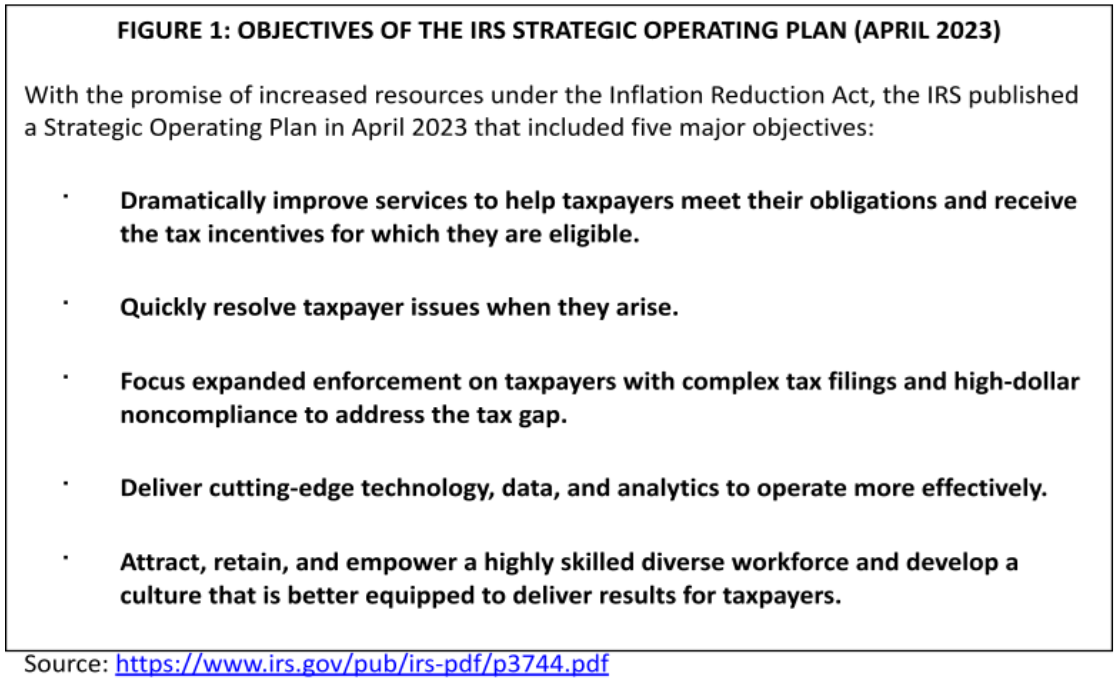

The IRS’s Strategic Operating Plan. In April 2023, the administration unveiled a Strategic Operating Plan (SOP) outlining its primary objectives for its increased funding under the IRA, including enhancing taxpayer services, modernizing IRS operations, and addressing tax evasion, particularly among high earners and large corporations (See Figure 1).[34] The plan lays out broad targets and timelines for some of its reform and modernization initiatives. The modernization objective includes goals of retiring legacy systems, enhancing employee data access, and upgrading security systems, yet provides intermittent information about the processes by which these changes will occur.

Upon its release, many observers criticized the SOP for its lack of specificity. NTUF noted that the plan omitted key details, like “specific qualitative goals for improved service, how the IRS will better measure and assess the tax gap, and how the IRS will square its expanded enforcement objectives with taxpayer rights and due process.”[35] A report from PricewaterhouseCoopers noted that the plan did not include details regarding the IRS’s “hiring goals, target audit rates, [or] the allocation of funds beyond the next two years” and that, at best, it should be looked at as a “high-level aspirational roadmap.”[36] In addition, the National Taxpayer Advocate expressed concerns about both “the lack of specificity and broad scope of the initiatives in the published plan.”[37]

In May 2024 the IRS released its first annual update to the SOP alongside a supplemental document. The supplemental document expands upon IRS’s progress on its outcomes for the SOP’s first major objective, which is to dramatically improve service. Improvements in this area that were completed in Fiscal Year 2024 include updates to both Individual Online Accounts and Tax Professional Online Accounts and new document uploading and e-filing options.[38] While the supplemental document lists Fiscal Year 2024 and Fiscal Year 2025 outcomes for the SOP’s fourth major objective, to modernize its technology, these outcomes remain vague. For example, some of the 2024 outcomes are: to initiate modern individual tax processing to be run in parallel with the legacy Individual Master File (IMF), to create synthetic data to share with external partners to improve insights, and to implement a new operating model, with increased partnership between the IT team and the rest of the IRS organization, allowing the IRS to more quickly deliver better products, tools, and improvements. Furthermore, none of the Fiscal Year 2024 outcomes have been completed.[39]

Ideas for Action in Modernizing the IRS

Informed by the discussions among the experts on the Taxpayers FIRST Advisory Board, NTUF offers the following recommendations for more efficient use of the increased funds provided to the IRS under the Inflation Reduction Act:

1. Produce an Enhanced Modernization Plan with Cost Analysis. The SOP outlines 42 initiatives designed to meet its five broad objectives, each of which, according to the IRS, “includes multiple key projects and milestones to measure progress.” And, for each milestone, the “plan includes specific timeframes based on year.”[40] But, while the topline numbers of projects and initiatives might seem impressive, the plan does not include any individualized cost estimates or analyses for any of its projects. The SOP includes “proposed investments” for each of the five broad objectives but lacks any per-project cost estimates. In addition, while the plan identifies basic timelines and benchmarks for the completion of various initiatives, it provides very little detail on the metrics the IRS will use to evaluate the success of any technology upgrades or service improvements. Such details have only become more important as the total amount of available funds were recently reduced. The 2024 annual update to the SOP and supplemental document do not provide much more clarity on the true cost of IRS modernization. The appendix of the supplemental document only lists two broad categories of spending under the IRS’s modernization objective: “Human Resource Information Technology (HRIT)” and “IRS Expansion.”[41]

To address these shortcomings, the IRS should provide more details on its modernization plans beyond those included in the SOP and the supplemental document released in 2024. Such information could be provided via a newly enhanced plan focused primarily on modernization. Whatever form it takes, the plan should include itemized cost analyses along with any relevant deadlines, deliverables, and benchmarks for each of its modernization initiatives. Any cost analysis should attempt to account for interactions between estimates and be accompanied by an analysis of the benefits of such expenditures. Providing the public with this type of information will ensure greater accountability and transparency for the IRS’s modernization efforts, ensuring each objective is both adequately planned and fully paid for.

2. Provide More Transparent Updates and Metrics. Over the past year, the IRS has gone to considerable lengths to tout its efforts to upgrade technology and improve services. However, the IRS has been very selective in the data it releases to the public. For example, the IRS publicly lauded itself for achieving an 87 percent Level of Service (LOS) in responding to taxpayer phone calls in 2023, along with improvements in digitized returns and the launch of new online tools.[42] While these developments objectively showed a substantial improvement over preceding years, they do not tell the full story. As the Taxpayer Advocate recently noted, the data released by the IRS when it announced LOS achievements failed to paint the full picture. For starters, the chosen LOS metric does not equate to the percentage of calls IRS assistors answered – the IRS actually only answered 35 percent of taxpayer calls it received. Metrics should also be collected about whether the taxpayer was able to get the help they were seeking from the call, as many private firms ask in post-call surveys. In addition, the LOS rates were not the same for all lines of service – the phone line for tax practitioners, for example, had only a 34 percent LOS with much longer average wait times. The IRS also temporarily reassigned employees from other customer service functions to answer phone lines to reach its LOS goals, leading to an increase in the backlog of amended returns and paper correspondence.[43]

Going forward, the IRS should be much more transparent when reporting on its various modernization and service initiatives. Any successes or failures should be expressed though clearly defined metrics that accurately reflect any progress being made. Whenever possible, such data should be released on a rolling basis, giving taxpayers and policymakers updates at a pace that is close to real-time. Making this kind of useful information public will allow for better feedback from stakeholders and increased accountability, all of which should ultimately result in better policy decisions at the IRS. The process of modernization should also result in more transparency as data collection and distribution becomes easier.

3. Accelerate the Pace of Modernization. The IRS has publicly committed to making significant technology improvements to streamline its processes, enhance data management, and increase overall efficiency. Notably, the SOP outlined plans to replace the IMF with “a modern, flexible system that will be more timely, accurate and complete for both taxpayers and employees.”[44] For this effort to be successful, the IRS must ensure its modernization efforts outpace or at least keep up with technological advancements in the broader environment. Simply replacing outdated technology with solutions that are only a little less antiquated will not serve the taxpayers interests.

Any new tools employed by the IRS – whether they are developed from scratch or purchased off-the-shelf – should match current IT standards and be readily updatable or replaceable to keep pace with future advancements. This standard should apply not only to technology tools used in enforcement, but in customer service and operations as well. One notable example is the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in its enforcement efforts, particularly with the identification and examination of complex partnership arrangements.[45] The IRS has long used AI to detect suspected identity theft, yet tax practitioners warn that it is often unable to distinguish between routine anomalies and intentional wrongdoing.[46] Therefore, it is critical to ensure that technologies are both appropriately modern and updated regularly with new information by an adequate force of properly trained information technology personnel. These staff should have access to subject matter expertise to ensure algorithms and other processes are well-informed in customer service, enforcement, and other areas. When advanced technologies are used for enforcement and compliance, taxpayers must also have access to prompt and accessible dispute resolution procedures that provide information about why the action was taken.

4. Use Some Enforcement Funds for Supportive Modernization Efforts. One major shortcoming of the IRA was its insufficient focus on modernization. However, the Commissioner should have some flexibility regarding use of that funding because many of the IRS’s modernization initiatives are essentially enforcement-related. Following the advice of stakeholders and policymakers across the ideological spectrum as well as an analysis of the organization’s needs, the administration should shift an appropriate portion of the IRS’s recently augmented funding from enforcement to modernization and technology improvements. If necessary, the IRS should work with Congress to amend any restrictions on the IRA’s funding that could hinder a shift to more important priorities. While enforcement is a critical IRS responsibility, focusing resources and attention on upgrading systems and processes in the near-term will bolster the IRS’s ability to fulfill all its mandates – including enforcement – further into the future. Therefore, enforcement funds redirected towards modernization should be directed at technologies that enhance enforcement, such as the Return Review Program (RRP).[47]

5. Add a Strategic Accountability Entity to the IRS Structure. Once again, the idea of modernizing the IRS and upgrading its IT is not new. Indeed, the IRS has been developing – and re-developing – modernization plans for decades now. But organizational complexities at the IRS tend to raise systemic barriers for the implementation of long-term IRS-wide strategies, including past modernization initiatives.

The IRS Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998 attempted to fill this gap by establishing the IRS Oversight Board – made up of presidential appointees confirmed by the Senate – to provide oversight and strategic guidance to the IRS. After failing to fill several vacancies, the Board has been effectively inactive, with no new appointments or significant activity for several years.

Congress and the IRS would benefit from a high-level panel of experts who provide ongoing, independent, non-adversarial guidance to the IRS and the Commissioner, particularly on medium- and long-term projects. The panel could be housed within the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), be a separate entity but whose appointments are not subject to Senate confirmation, or supplement existing Treasury and IRS advisory panels. If implemented properly, it could help minimize disruption and ensure modernization initiatives are not abandoned or rewritten with every change in leadership or new administration.

Conclusion

The IRA provided the IRS with a massive boost in resources. While the authors of the statute were clearly focused on enforcement, the historic problems at the IRS run much deeper. Every IRS mandate – from tax enforcement to tax administration to customer service – has been weakened by the use of outdated technology and inefficient processes. That being the case, redirecting more resources and attention toward modernization should help improve the IRS’s functions across the board.

Going forward, the IRS should be required to account for the considerable resources it intends to spend, explaining in detail what solutions it wants to implement, how much they will cost, and the impact they will have on taxpayers. While the IRS has already committed to providing continual updates on its modernization progress, these updates need to come more often and provide more detailed and useful information for taxpayers, tax practitioners, elected leaders, and other stakeholders. Increasing transparency and accountability for the IRS’s modernization efforts should help taxpayers get a better return on their historically sizable investment.

NTUF extends gratitude to the following individuals who contributed their input to discussions that informed this paper. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of any individual contributor or organization associated with the contributors.

Fred Goldberg Former IRS Commissioner and Chief Counsel | Nina Olson Executive Director of the Center for Taxpayer Rights and former IRS National Taxpayer Advocate |

Caroline Bruckner Tax professor at American University’s Kogod School of Business and the Managing Director of the Kogod Tax Policy Center | Pete Sepp President of the National Taxpayers Union |

Fred Forman Former IRS Associate Commissioner of Business Systems Modernization | Adam Michel Director of Tax Policy Studies at the Cato Institute |

Joe Bishop-Henchman Executive Vice President of the National Taxpayers Union Foundation | Erica York Senior Economist and Research Manager with Tax Foundation’s Center for Federal Tax Policy |

Janet Holtzblatt Senior Fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center | Jason J. Fichtner Vice President and Chief Economist at the Bipartisan Policy Center |

Jason DeCuir Co-owner and Partner at Advantous Consulting, a leading multi-state tax services firm | Jeff Trinca Founding Vice President of Van Scoyoc Associates |

Barbara J. Robles Former Principal Economist with the Federal Reserve Board of Governors | Alex Brill Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute |

Gordon Gray Director of Fiscal Policy at the American Action Forum | Graham O’Neill Tax Policy Strategist at Prosperity Now |

Leslie Book Professor of Law at Villanova Charles Widger School of Law | Andrew Lautz Associate Director for the Economic Policy Program at the Bipartisan Policy Center |

Peter Mills Senior Manager of tax policy and advocacy at the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants | Megan Killian, CAE Executive Vice President at the National Association of Enrolled Agents |

Ben Ritz Vice President of Policy Development & Director, Center for Funding America's Future at the Progressive Policy Institute | Demian Brady Vice President of Research of the National Taxpayers Union Foundation |

Andrew Wilford Senior Policy Analyst of the National Taxpayers Union Foundation |

|

[1] Congressional Research Service, “IRS-Related Funding in the Inflation Reduction Act,” CRS-IN11977, Updated October 20, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11977.

[2] Internal Revenue Service Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998, Pub. L. No. 105–206, 112 Stat. 685. Retrieved from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-105publ206/pdf/PLAW-105publ206.pdf

[3] American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, Pub. L. No. 111–5, 123 Stat. 115. Retrieved from: https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ5/PLAW-111publ5.pdf.

[4] Taxpayer First Act, Pub. L. No. 116–25, 113 Stat. 981. Retrieved from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-116publ25/pdf/PLAW-116publ25.pdf.

[5] ‘Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, Pub. L. No. 116–136, 134 Stat. 281. Retrieved from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-116publ136/pdf/PLAW-116publ136.pdf.

[6]General Service Administration, Federal IT Dashboard, Last Visited March 8, 2023. Retrieved from: https://itdashboard.gov/itportfoliIT Portfolio Dashboardodashboard.

[7] Bryan Hickman, “Agile, Adaptable, Advanced: Winning with Smart IT Investments,” National Taxpayers Union, April 28, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.ntu.org/publications/detail/agile-adaptable-advanced-winning-with-smart-it-investments.

[8] U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Information Technology: Additional Actions and Oversight Urgently Needed to Reduce Waste and Improve Performance in Acquisitions and Operations,” GAO-15-675T, June 10, 2015. Retrieved from: https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/670745.pdf.

[9] National Taxpayer Advocate 2021 Purple Book. Retrieved from: https://www.taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ARC20_PurpleBook_01_StrengthRights_2.pdf.

[10] Tax Policy Center. Briefing Book: What does the IRS do and how can it be improved?. May 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-does-irs-do-and-how-can-it-be-improved.

[11] U.S. Government Accountability Office. Information Technology: IRS Needs to Complete Modernization Plans and Fully Address Cloud Computing Requirements, GAO-23-104719 Jan. 12, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-104719.

[12] Strategic Technology Partners, “Providing Expert Support Toward Replacing the Oldest System in the Federal Government,” last visited Feb. 29, 2024. Retrieved from: https://stpfederal.com/case-studies/providing-expert-support-toward-replacing-the-oldest-system-in-the-federal-government/.

[13] Frank Konkel, “The IRS System Processing Your Taxes is Almost 60 Years Old,” Nextgov/FWC, Mar. 19, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.nextgov.com/modernization/2018/03/irs-system-processing-your-taxes-almost-60-years-old/146770/.

[14] Government Accountability Office, “Information Technology: IRS Needs to Complete Modernization Plans and Fully Address Cloud Computing Requirements,” GAO-23-104719, Jan. 12, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-104719.

[15] Aaron Boyd and Frank Konkel, “IRS’ 60-Year-Old IT System Failed on Tax Day Due to New Hardware,” Nextgov/FWC, April 19, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.nextgov.com/modernization/2018/04/irs-60-year-old-it-system-failed-tax-day-due-new-hardware/147598/.

[16] National Taxpayer Advocate, “The NTA Reimagines the IRS with a Dramatically Improved Taxpayer Experience: Part Two,” Last Updated Feb. 9, 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/news/nta-blog/nta-blog-the-nta-reimagines-the-irs-with-a-dramatically-improved-taxpayer-experience-part-two/2022/09/.

[17] Treasury Inspector General For Tax Administration, “The Enterprise Case Management System Did Not

Consistently Meet Cloud Security Requirements,” March 27, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.tigta.gov/sites/default/files/reports/2023-03/202320018fr.pdf.

[18] Government Accountability Office, “Security of Taxpayer Information: IRS Needs to Address Critical Safeguard Weaknesses,” August 14, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105395.

[19] Demian Brady, “Your Tax Data at Risk: Why the IRS Must Prioritize Cybersecurity,” April 18, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.ntu.org/foundation/detail/your-tax-data-at-risk-why-the-irs-must-prioritize-cybersecurity.

[20] National Taxpayer Advocate, “Fiscal Year 2023 Objectives Report to Congress.” Retrieved from: https://www.taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/reports/2023-objectives-report-to-congress/.

[21] Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, “The Internal Revenue Service Has Experienced

Challenges in Transitioning to Electronic Records,” Sept. 6, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.tigta.gov/sites/default/files/reports/2023-09/202310050fr.pdf.

[22] Daniel Werfel, “Testimony before the House Oversight and Accountability Committee Subcommittees on Government Operations and the Federal Workforce and Health Care and Financial Services on IRS Operations,” October 24, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/written-testimony-of-daniel-werfel-commissioner-internal-revenue-service-before-the-hoac-subcommittees-on-government-operations-and-the-federal-workforce-and-health-care-and-financial-services-and-irs-operations.

[23] Jory Heckman, “IRS commissioner finalizing plans to rebuild workforce over next decade,” Federal News Network, April 19, 2023. Retrieved from: https://federalnewsnetwork.com/hiring-retention/2023/04/irs-commissioner-finalizing-plans-to-rebuild-workforce-over-next-decade/.

[24] National Taxpayer Advocate, “Annual Report to Congress 2021.” Retrieved from: https://www.taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/ARC21_Pro_TPR-Assessment.pdf

[25] Joe Davidson, “IRS tech is so ‘archaic’ the agency struggles to find people to work it,” Washington Post, Feb. 23, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/02/24/irs-technology-gao-report-archaic/.

[26] Congressional Research Service, “IRS-Related Funding in the Inflation Reduction Act,” Updated October 20, 2022. Retrieved from: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11977.

[27] Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, “Quarterly Snapshot: The IRS’s Inflation Reduction Act Spending Through September 30, 2023,” Jan. 29, 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.tigta.gov/sites/default/files/reports/2024-01/2024ier007fr.pdf.

[28] IRS, “Internal Revenue Service Inflation Reduction Act Strategic Operating Plan FY 2023 – 2031,” https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p3744.pdf.

[29] Tobias Burns, “6 takeaways as IRS chief takes heat from House panel,” The Hill, Feb. 15, 2024. Retrieved from: https://thehill.com/business/4470982-6-takeaways-as-irs-chief-takes-heat-from-house-panel/.

[30] Kevin McCarthy (@SpeakerMcCarthy), X (formerly known as Twitter), Jan. 9, 2023. Retrieved from: https://twitter.com/SpeakerMcCarthy/status/1612640200081002496.

[31]Andrew Lautz, “NTU Urges Support for Bill to Reduce IRS Overspending,” Jan. 3, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.ntu.org/publications/detail/ntu-urges-support-for-bill-to-reduce-irs-overspending.

[32] Andrew Lautz, “IRS Funding Reallocation Could Improve Taxpayer Service, Modernization Efforts,” March 31, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.ntu.org/foundation/detail/irs-funding-reallocation-could-improve-taxpayer-service-modernization-efforts.

[33] Julie Zauzmer Weil, “IRS: Fund us, and we’ll collect hundreds of billions from tax cheaters,” The Washington Post, Feb. 7, 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2024/02/06/irs-tax-evasion-study-budget/.

[34] IRS, “Internal Revenue Service Inflation Reduction Act Strategic Operating Plan FY 2023 – 2031,” https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p3744.pdf.

[35] Pete Sepp, IRS $80 Billion Spending Plan Lacks Key Details Needed for Taxpayers,” NTUF, Apr. 6, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.ntu.org/foundation/detail/irs-80-billion-spending-plan-lacks-key-details-needed-for-taxpayers.

[36] “IRS Strategic Operating Plan identifies priorities for improved services, compliance,” PwC, Apr. 12, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.pwc.com/us/en/tax-services/publications/insights/assets/pwc-irs-strategic-operating-plan-identifies-transformation-priorities.pdf.

[37] National Taxpayer Advocate, “Fiscal Year 2023 Annual Report to Congress.” Retrieved from: https://www.taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/ARC23_MSP_03_Transparency.pdf.

[38] IRS, “IRA Strategic Operating Plan Annual Update,” May 2, 2024, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p3744b.pdf.

[39] IRS, “IRA Strategic Operating Plan Annual Update,” May 2, 2024, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p3744b.pdf.

[40] IRS, “IRS unveils Strategic Operating Plan; ambitious effort details a decade of change,” April 6, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-unveils-strategic-operating-plan-ambitious-effort-details-a-decade-of-change.

[41] IRS, “IRA Strategic Operating Plan Annual Update,” May 2, 2024, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p3744b.pdf.

[42] IRS, “Inflation Reduction Act 1-year report card: IRS delivers dramatically improved 2023 filing season service, modernizes technology, pursues high-income individuals evading taxes,” Aug. 16, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/inflation-reduction-act-1-year-report-card-irs-delivers-dramatically-improved-2023-filing-season-service-modernizes-technology-pursues-high-income-individuals-evading-taxes.

[43] National Taxpayer Advocate, Fiscal Year 2023 Annual Report to Congress. Retrieved from: https://www.taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/ARC23_MSP_03_Transparency.pdf.

[44] IRS, “Internal Revenue Service Inflation Reduction Act Strategic Operating Plan FY 2023 – 2031,” https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p3744.pdf.

[45] IRS, “IRS announces sweeping effort to restore fairness to tax system with Inflation Reduction Act funding; new compliance efforts focused on increasing scrutiny on high-income, partnerships, corporations and promoters abusing tax rules on the books.” Sept. 8, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-announces-sweeping-effort-to-restore-fairness-to-tax-system-with-inflation-reduction-act-funding-new-compliance-efforts.

[46] Michael Cohn, “AI in IRS audits could be a game-changer, but comes with pitfalls,” Accounting Today, Sept. 11, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.accountingtoday.com/news/irs-use-of-ai-in-tax-audits-could-be-a-game-changer-but-with-pitfalls.

[47] IRS, “IRS Integrated Modernization Business Plan,” April 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p5336.pdf.