For decades, protectionists have claimed that free trade policies have led to rampant unemployment in the American manufacturing sector. They often cite our growing trade deficits with major exporters of manufactured goods like China as the root cause of such supposed unemployment. For example, the Coalition for a Prosperous America alleges that the trade deficit with China has cost us 2.98 million manufacturing jobs since 2001.

Do the protectionists’ claims carry any water? Are they correct in correlating free trade and growing trade deficits with upticks in unemployment in American manufacturing?

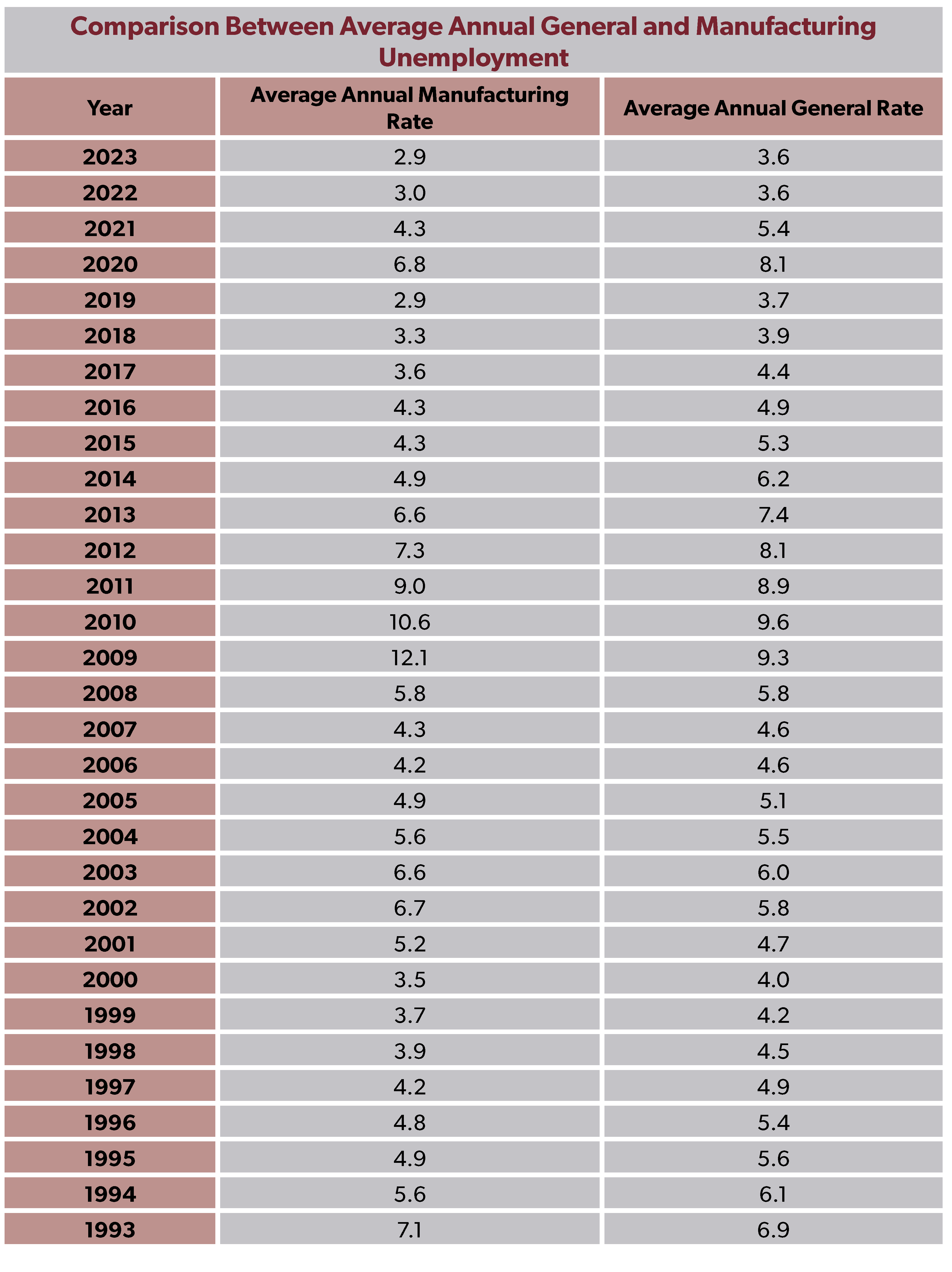

In short, no. While it is true that the United States’s trade deficit has grown from $92.49 billion in 1994 to $773.4 billion in 2023, unemployment in the manufacturing sector declined steadily over the same period of time. Unemployment trends in the manufacturing sector correlate strongly with general unemployment trends, as shown below. Despite what detractors of free trade may claim, policies that enhance growth and employment in the general economy seem to carry those benefits over to the manufacturing sector.

Statistical analysis reveals that the average annual manufacturing and general unemployment rates from the past 30 years have a strong positive linear relationship. In other words, when the overall unemployment rate goes up or down, the manufacturing unemployment rate tends to go up or down in a similar way. While this relationship in and of itself is insufficient to conclude that the two variables have shared causes, it is plausible based on economic theory to suggest that the same macroeconomic factors drive both general and manufacturing unemployment rates.

While it may be true that protectionist policies encourage employment in the narrow industries being protected, this comes at the expense of the economic welfare of society as a whole and employment in other industries. For instance, Section 232 tariffs may have “created” 1,000 jobs in the steel production industry but they reduced manufacturing employment on net by 75,000 jobs. Tariffs on baby formula may have stimulated domestic production but prompted a shortage and raised the price of baby formula. The 1930 Smoot-Hawley Act, which sought to boost U.S. industries competing with foreign imports, ended up causing a significant reduction in employment in export industries.

Rather than engaging in a tradeoff that will necessarily make society as a whole worse off, those who seek to promote domestic manufacturing should focus their energies on advocating for pro-growth policies like the extension of the full and immediate expensing provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the re-establishment of full deductibility of research & development costs, and restoring deductibility of depreciation and amortization costs.