Introduction

A lawsuit filed by a current member of Congress and several former members seeks congressional back pay that could cost taxpayers tens of millions of dollars. The lawsuit argues that Congress cannot constitutionally block automatic pay increases for itself.

Since 1989, federal law has set an automatic annual cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) for members of Congress unless they vote to block it. The lawsuit argues that the 21 times Congress voted to block the COLA violated the Constitution.

As first filed, the lawsuit sought back pay for all members who served since 1994. Accounting for the annual COLA rate increases since then would cost taxpayers an estimated $603 million for the additional compensation. However, Judge Eric G. Bruggink recently ruled that claims prior to March 2018 cannot be litigated, reducing the potential cost to $69 million.

Congress often blocks pay raises due to concerns over fiscal responsibility and the optics of increasing its members’ salaries during economic downturns. The plaintiffs, elected to serve the public trust, are now seeking back pay. With a federal debt of over $35 trillion, this action undermines that trust. Additionally, lawmakers already earn far more than most Americans, and this lawsuit, if successful, would only add to the deficit.

About Congressional Salaries and the Lawsuit

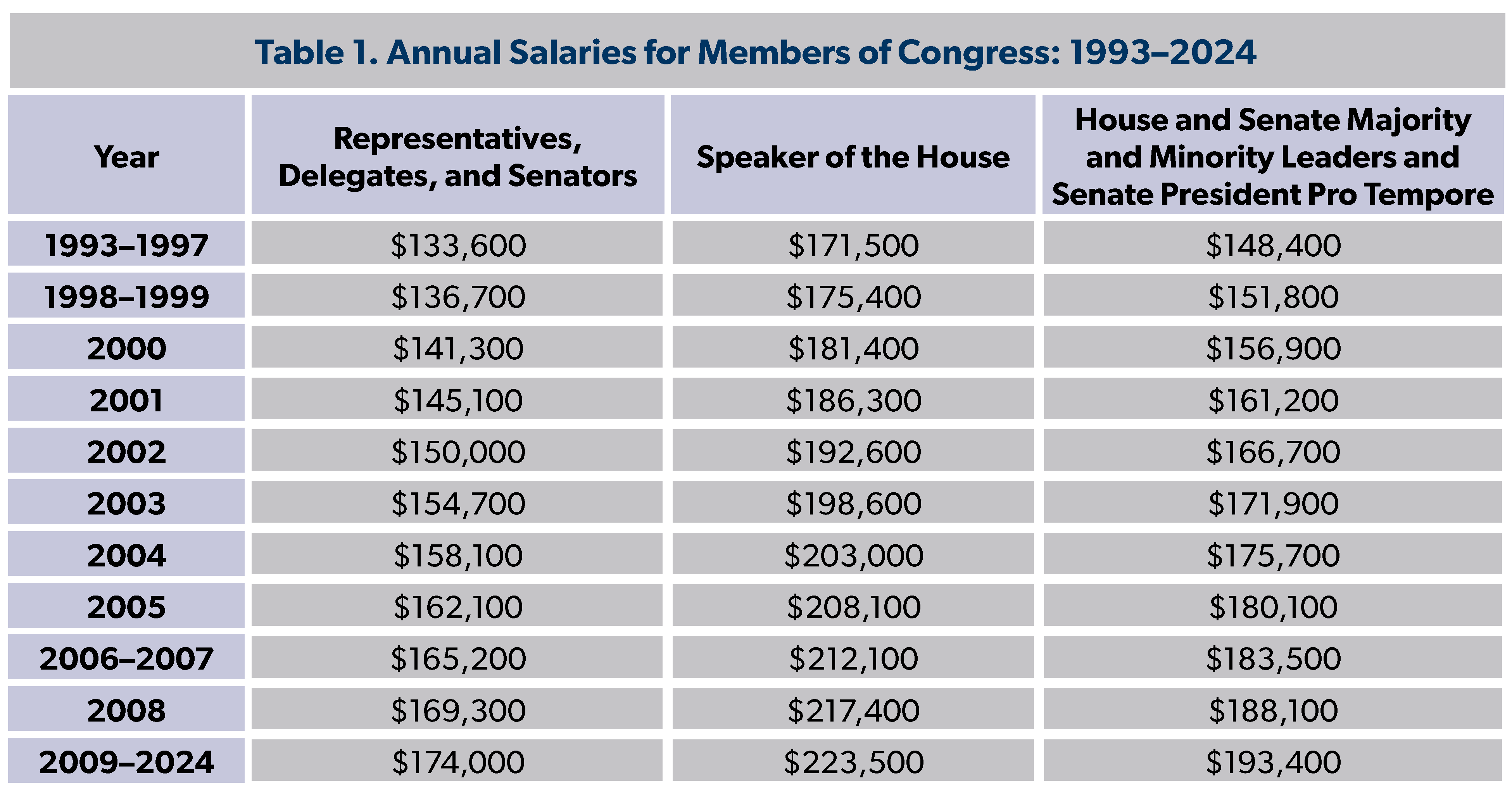

Under current law, the 535 rank-and-file representatives, delegates, and senators are paid $174,000 per year.[1] Members in leadership positions receive higher salaries, with the Speaker of the House earning $223,500, and the House and Senate Majority and Minority Leaders, along with the Senate President Pro Tempore, earning $193,400.

The Ethics Reform Act of 1989 established automatic annual COLAs for members of Congress, with the adjustments based on changes in private sector wages and rounded to the nearest hundred. However, congressional salaries in practice have been frozen since 2009 due to regular votes by Congress to block the COLA increases. Table 1 below shows the total salaries paid to members of Congress since 1993.

In March 2024, the lawsuit was filed by Representative Rick Crawford (R-AR) and former Representatives Rodney Davis (R-IL), Tom Davis (R-VA), Ed Perlmutter (D-CO), and former Senator Mark Kirk (R-IL) in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims against the federal government, arguing that all of the pay freezes that Congress approved “unconstitutionally suppressed” salaries for members in violation of the 27thAmendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Ratified in 1992, the amendment states: “No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of Representatives shall have intervened.” Initially approved by Congress in 1789, the Amendment was finally ratified in 1992 due a campaign led by Gregory D. Watson, who had written a paper in college about this issue (ironically receiving a C grade), arguing that the amendment could still be adopted by the states because Congress had not set a deadline for ratification.

A central argument of the lawsuit is that early voting and absentee voting in several states effectively caused elections to begin before the formal election date in November. As a result, the plaintiffs argue that the pay freeze votes which occurred after early voting had started failed to meet the constitutional requirement for an “intervening election” before changes in pay took effect. The plaintiffs further argue that the suppression of COLAs affected not only their annual salaries, but also their retirement benefits, which are calculated based on their highest salary years.

Taxpayer Savings from the Approved Salary Freezes

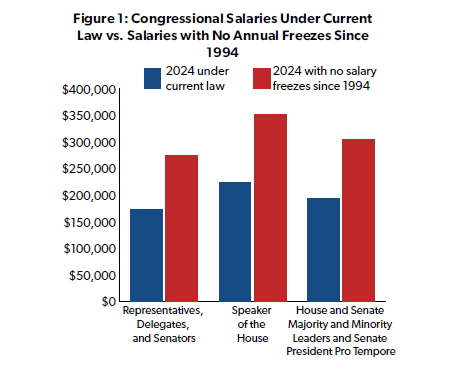

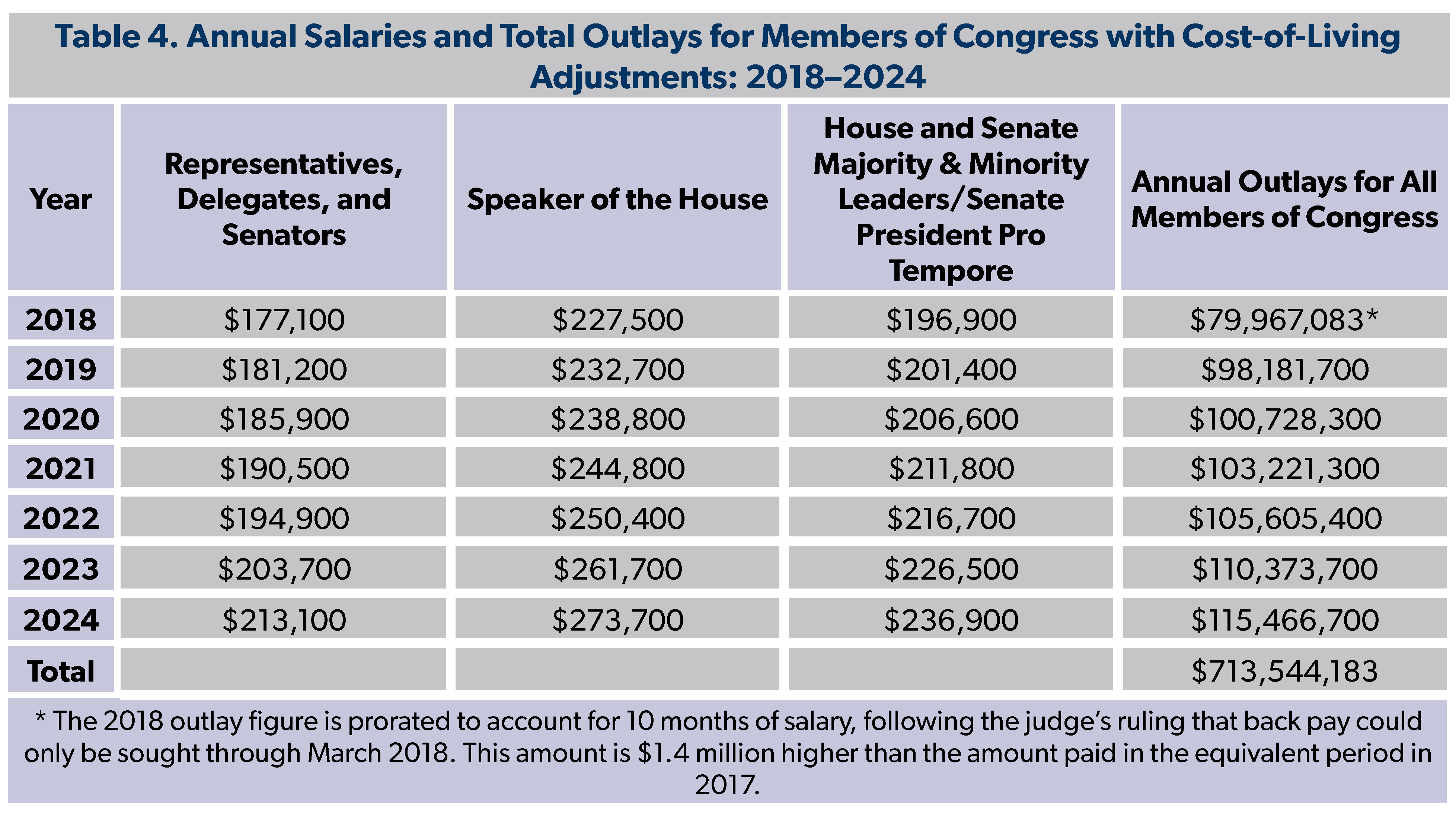

If the plaintiffs win, the underlying back pay could cost nearly $603 million if every sitting and former member since the first COLA freeze in 1994 was eligible for back pay. To estimate the taxpayer savings from the cumulative salary freezes, NTUF compiled the annual salaries for rank-and-file representatives, senators, and leadership positions (including the Speaker of the House, House and Senate Majority and Minority leaders, and the Senate President Pro Tempore). Additionally, data from the Congressional Research Service on the annual rates of the blocked COLAs was used to calculate what annual salaries for all members of Congress would have been if the 21 COLA increases had not been blocked.

If Congress had not blocked any of the annual COLAs, member salaries would be 58 percent higher in 2024 than they are under current law: $274,900 instead of $174,000. The 21 votes for pay freezes have saved taxpayers a combined total of $603,184,300 in additional salary paid to members of Congress.

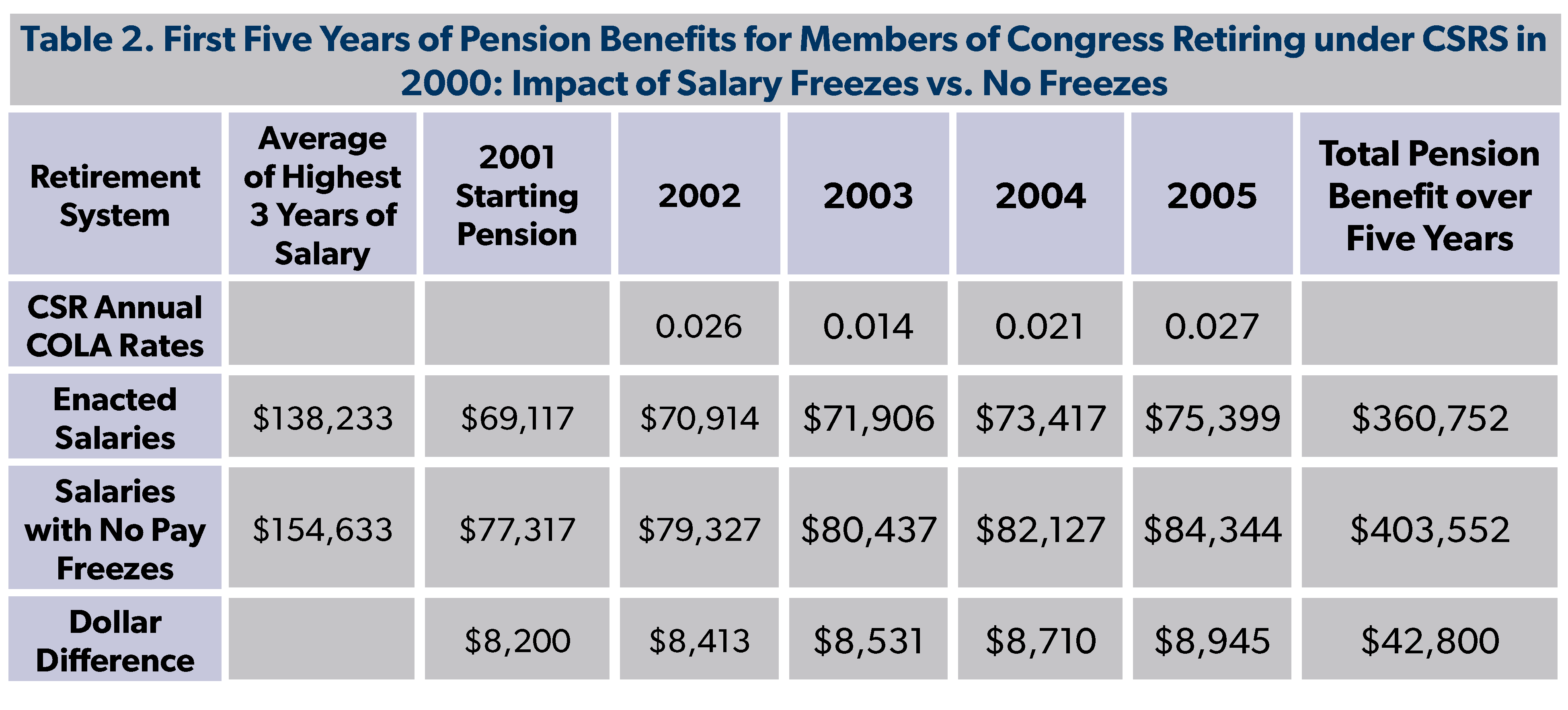

This would also greatly increase costs for retirement benefits for members of Congress. Members with at least five years of service are eligible for a pension. Members elected before 1984 are eligible to participate in the Civil Service Retirement System (CSRS), which offers a generous 2.5 percent accrual rate. The starting pension amount is determined by multiplying the number of years in office by the average of the three highest years of salary, multiplied by 2.5 percent. The starting benefit cannot exceed 80 percent of the final salary.

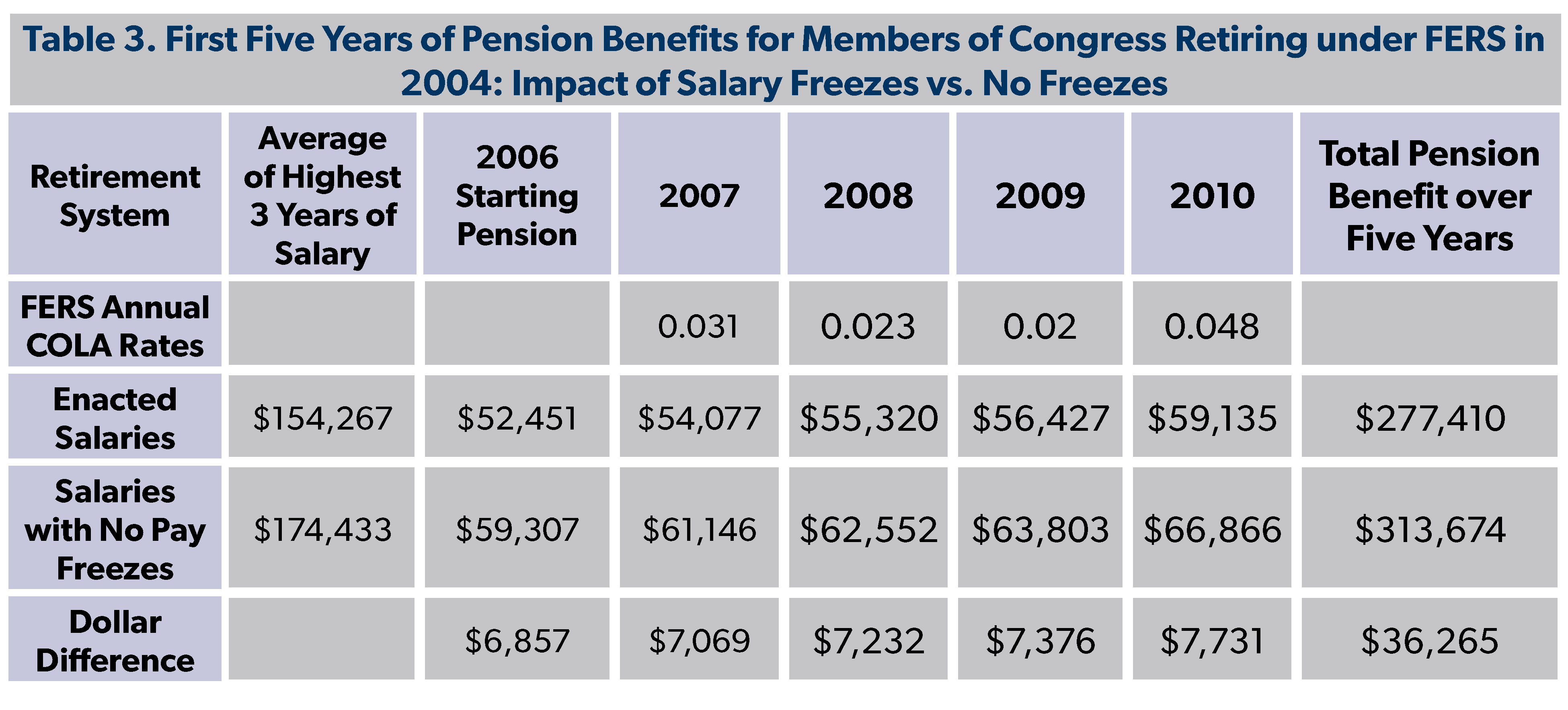

A less generous pension program, the Federal Employees’ Retirement System (FERS), went into effect in 1987 for members elected starting in 1984. The formula is generally the same as above, except that the accrual rate is 1.7 percent for the first 20 years of service and remaining years accrue at 1.0 percent.

According to a Congressional Research Service report, as of October 2022, 261 former members of Congress retired under CSRS and were receiving an average annual pension of $84,504, which amounts to total outlays of $22,055,544 and 358 former Members retired under FERS with an average pension of $45,276, totaling $16,208,808. This amounts to total outlays of $38,264,352 to support pensions for former members of Congress.

Although the formulas used to calculate pension benefits are publicly known, estimating the precise savings due to the blocking of automatic COLAs is complicated by the lack of detailed, individual data from the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), which administers the congressional pension program. Without specific data on individuals participating in the program, it’s difficult to calculate the exact savings that resulted from these pay freezes.

To help illustrate the impact of the potential savings on pension benefits, NTUF modeled the impact of COLAs by comparing rank-and-file members with 20 years of service with and without the annual COLAs:

- Under CSRS, a member retiring in 2000 would have received a starting pension that was $8,200 higher if all COLAs had been applied. Over the next four years, with CSRS COLAs, the cumulative payout over five years would have been $42,800 higher.

- Under FERS, assuming service began in 1985 and the member retired after 20 years, the starting pension would have been $6,900 higher with the COLAs. With FERS COLAs factored in over the next four years, the total payout over five years would be $36,300 higher.

Given that congressional pensions are calculated based on a member’s highest salary, the freezing of COLAs has directly limited the growth of these pensions, resulting in millions of dollars in saved pension outlays over time. This broader impact on pensions illustrates how blocking COLAs not only saves taxpayer dollars for current salary costs, but also contains long-term financial liabilities for the federal government, creating substantial and ongoing taxpayer savings.

Potential Costs to Taxpayers from the Congressional Members’ Lawsuit

In a recent ruling, Judge Bruggink of the U.S. Court of Federal Claims limited the scope of the lawsuit to claims starting from March 2018. The court also dismissed claims in the case related to retirement benefits. This reduces the potential cost to taxpayers. Since 2018, the combined salary for all representatives, delegates, and senators has cost $94.3 million per year, for a total of $660.0 million.

If the pay increases had not been blocked, congressional salaries would be 22 percent higher in 2024 than they are under current law, with total outlays of $713.5 million, $69.3 million higher than under current law (including the prorated amount in 2018).

By comparison, the average public school teacher across the U.S. earned $66,397 in 2022. That money for back pay to Members of Congress could fund the salaries of over 1,000 public school teachers.

For another example, the average household in the U.S. spent $9,985 on food in 2023, with groceries accounting for $6,053 of that total. This marks an increase of approximately 6 percent from the previous year due to inflation. Therefore, the $69.3 million increase in outlays for back pay to Members of Congress would be enough to cover the annual grocery bills for over 11,400 households across the U.S.

This additional deficit spending would also increase costs to service the debt. According to the Congressional Budget Office’s interactive spreadsheet, an additional $69.3 million in 2025 would increase debt service costs by about a half a million dollars and by $3 million annually in subsequent years, for a cumulative budget impact of $96 million over the decade.

Looking ahead, if the lawsuit succeeds, Congress would need to take a more proactive role in voting to freeze COLAs well in advance of election years.

Setting the Record Straight on the Meaning of the 27th Amendment

While there are many better destinations for taxpayer dollars than the pockets of members of Congress, the legal argument being forward by the plaintiffs is also dubious. As noted above, the text of the Amendment reads that there shall be no law varying the compensation of Members of Congress shall take effect “until an election of Representatives shall have intervened.” The limits established by the 27th Amendment were not designed to prevent Congress from protecting taxpayers from additional financial burdens, but rather to prevent lawmakers from padding their pockets on the taxpayers' tab without facing the electorate first.

What became the 27th Amendment was authored by James Madison, known as the “Father of the Constitution” for his role in drafting that document and also the Bill of Rights, the crux of which was to impose checks and balances on government and provide protections for citizens. He first proposed this amendment on June 8, 1789, during the very First Congress to clarify Article I, Section 6, Clause 1 of the Constitution, which states:

The Senators and Representatives shall receive a Compensation for their Services, to be ascertained by Law, and paid out of the Treasury of the United States.

After extensive debate about the sources of congressional salaries, it was determined that it should be paid by the federal treasury rather than the states. This would strengthen the federal system and protect members from undue influence from state governments in the event that they had control over the salary of a representative. This would also ensure fairness so that members were paid the same regardless of the wealth of the various states.

As the Constitution was being debated, the Anti-Federalists raised strong objections to its various provisions, including the compensation clause. They feared that this would allow Congress to unjustly increase its own pay, since people in power can be prone to corruption.

In 1992, New York Law School Professor Richard R. Bernstein provided a review of the arguments raised against the compensation provision. For example, at the Virginia ratifying convention in June 1788, Patrick Henry, warned that allowing Members of Congress to set their own salaries without any limits or restraints would inevitably lead to abuses. He argued that this power gave legislators the ability to “indulge themselves to the fullest extent by making their compensation as high as they please.” Other arguments include:

- an anonymous writer in New Hampshire: “How far Congress will extend this power . . . there is no man alive can tell—It is left without bound or limitation—and we may be sure, from the craving appetites of men for gain, it will be stretched as far as the patience, and abilities of the people will bear. European fashions have been transplanted into America. The high taste of foreign Courts will be relished by Congress. They must live in all the splendor of equipage and attendance. Their revenue must be equivalent. This being an infant country, and besides loaded with a large debt, will by no means be able to support it.”

- A pseudonymous Massachusetts newspaper essayist “Cornelius”: This part of the Constitution . . . [is] calculated, not only to enhance the expense of the federal government to a degree that will be truly burdensome; but also, to increase that luxury and extravagance, in general, which threatens the ruin of the United States.”

Following these debates, the 27th Amendment remained largely dormant for nearly two centuries until momentum to ratify it resurfaced in the late 20th century, fueled by concerns over government accountability and growing public sentiment against the perceived self-serving actions of members of Congress.

In 1982, Gregory Watson, an undergraduate student at the University of Texas at Austin, discovered that Madison’s proposed amendment had never expired and could still be ratified. Watson then launched a grassroots campaign that gradually gained momentum across numerous states. By 1992, thanks in large part to the efforts of Watson, the 27th Amendment was ratified, ensuring that Congressional pay raises would only take effect after a subsequent election, thus upholding Madison’s original intent of protecting taxpayers from unjust self-enrichment by legislators.

In introducing what was ratified as the 27th Amendment over 200 years later, Madison stated that although he thought it would be unlikely that Congress would abuse its authority to set its own salary, there should be protections to prevent members from voting to enrich themselves:

I do not believe this is a power which, in the ordinary course of government, is likely to be abused, perhaps of all the powers granted, it is least likely to abuse; but there is a seeming impropriety in leaving any set of men without controul [sic] to put their hand into the public coffers, to take out money to put in their pockets; there is a seeming indecorum in such power, which leads me to propose a change. We have a guide to this alteration in several of the amendments which the different conventions have proposed. I have gone therefore so far as to fix it, that no law, varying the compensation, shall operate until there is a change in the legislature; in which case it cannot be for the particular benefit of those who are concerned in determining the value of the service.

While the overwhelming focus of the debates surrounding the congressional compensation provision in the Constitution centered on concerns about Congress abusing this power for personal gain, there was a notable concern raised in the opposite direction. Representative Theodore Sedgwick of Massachusetts argued that if Congress reduced its pay, this could deter qualified candidates from seeking office, limiting public service to those with wealth. While concerns like Sedgwick’s highlighted the need for reasonable pay to attract qualified candidates, the amendment was designed to ensure that lawmakers cannot immediately benefit from any pay raises they enact, creating a safeguard against self-dealing.

Conclusion

It is very disappointing that the current and former members of Congress and the former Attorney General of the Commonwealth of Virginia are bringing this lawsuit. Although agencies of the federal government are named as defendants in this case, the ultimate target is taxpayers who will be stuck with more deficit spending if it is successful.

This lawsuit not only ultimately targets taxpayers, but also mangles the interpretation of the 27th Amendment. The Amendment’s goal was clear: to prevent members of Congress from padding their own pockets without facing electoral accountability. It was not designed to prevent Congress from freezing its own salaries in the name of fiscal responsibility. Their legal argument flies in the face of both the text and the meaning of the Amendment, which was to protect taxpayers, not enrich lawmakers.

[1] There are also six delegates in the 118th Congress representing the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Guam, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands.