(pdf)

Since the beginning of state-imposed lockdowns, many Americans have gone about a monumental shift in how they work. One recent study estimated that more than 50 million Americans have begun teleworking since the arrival of the coronavirus in the United States.[1]

While that is a huge shift for affected workers to deal with, it also has consequences for a tax system that focuses primarily on the physical location of employees when they perform their jobs. As our previous analysis on this topic explained, this can mean incurring new tax compliance obligations for employees who regularly commute across state lines.[2] NTUF conservatively estimated that at least 2 million Americans could be facing new filing obligations, and potentially even the threat of double taxation.

If left unchecked, this could mean that employees working from home might be slapped with new tax obligations as a result of complying with public health directives. Not only that, but medical or emergency volunteers traveling across state lines may as well.[3] Faced with the tragedy of thousands of American deaths, the last thing we should be doing is punishing Americans with new tax obligations for doing what public health officials are advising.

But it’s not just individual taxpayers who are affected. Businesses with employees who have switched to remote work in different tax jurisdictions than the location of their usual office can face exposure to new taxing jurisdictions and suddenly find their apportionment for business income tax changed significantly.

While such a rigid interpretation of tax law in the middle of a pandemic is callous regardless, it is made even more so by the fact that remote workers and the businesses allowing employees to work remotely are doing what public health experts and government officials have been asking Americans to do from the pandemic’s outset: stay at home and limit exposure to other individuals. When states are asking American individuals and businesses to make such drastic changes for the sake of public safety, it should not be used as an opportunity to subject compliant Americans to additional tax exposure for their compliance.

The State of Remote Work Nexus Policies

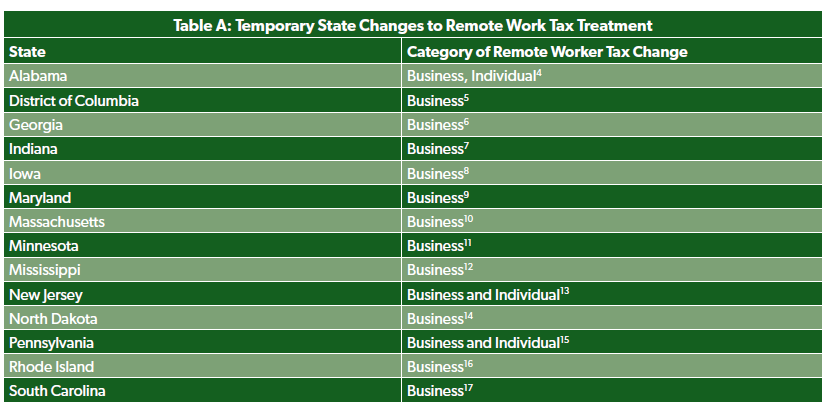

Despite the wisdom of ensuring fair tax treatment of temporarily remote employees, the majority of states have yet to act to clarify tax treatment of coronavirus-related remote work. Of those that have announced a policy change, the majority have only done so for business taxes.

Just three states — Alabama, New Jersey and Pennsylvania — have stated that employees working remotely in their states will be considered to be working from their primary office during the period of national emergency. Others, such as Massachusetts and Maryland, have affirmatively stated that they will not be making any changes to how they treat individual income taxes during the pandemic. Table A breaks down the policy announcements that states have made regarding how they treat remote work during the pandemic.

In addition, Ohio has acted to simplify its municipal income tax system for remote workers for the duration of the pandemic. While employees generally owe income taxes to an Ohio municipality once they work there for more than twenty days, the state recently clarified that it would treat remote work as work from the primary office site for municipal income tax purposes.

While those states that have taken steps to simplify remote work tax treatment should be commended, the reality is that not nearly enough have. Legislation is needed at the federal level to standardize tax treatment for Americans working remotely due to the pandemic.

Federal Legislative Responses

Fortunately, Congress could address this problem fairly easily. Legislation addressing pandemic-related remote work at the federal level should consist of both business and individual relief.

Individual Income Tax

On the individual side, relief for remote workers should specify that, for the 2020 fiscal year and the length of the national emergency, employees working remotely due to the pandemic should be considered to be working from their primary worksite for tax purposes.

This would ensure that taxpayers working in a different state as a result of COVID-19 are not subjected to new tax filing and payment obligations, and the paperwork burdens and audit risks associated with them. Americans complying with public health guidelines should not be punished with new tax paperwork.

Similar efforts to simplify the tax treatment of remote workers more generally (not specific to the pandemic period) came in the form of the Mobile Workforce State Income Tax Simplification Act of 2020.[18] This bipartisan legislation would bar states from claiming a slice of the tax income of remote workers until they had worked in that state for more than 30 days, effectively prohibiting aggressive efforts to collect a few day’s worth of income tax from someone traveling to the state for a conference or trade show, for example.

This legislation would provide useful language for addressing the individual side of relief for remote work while accomplishing the short-term goal of ensuring reasonable tax treatment of Americans forced to work remotely by lockdown mandates. More specifically, virtually the entirety of the Mobile Workforce bill’s language could be used in COVID-related remote work legislation, with a new section being added to address rules related specifically to the pandemic period.

A new section addressing tax rules during the pandemic could be structured in a number of ways. One approach would be to simply state that work performed in 2020 is subject to a higher threshold of days before a state can lay claim to income taxes associated with it. A period of at least 90 days would approximate the length of workplace shutdowns in many states across the country and would have the virtue of being easy to understand and administer.

Another approach would be to limit applicability of the legislation’s protections to remote work performed specifically because of the COVID-19 crisis (as opposed to remote work that might have occurred regardless of the public health situation), with associated definitions of what work qualifies as such. This could be subjected to a specific day limit, or it could be tied to the length of the President’s emergency declaration under the Stafford Act, which was declared on March 13th, 2020 and is still in force.

Business Income Tax

Just as individuals newly working from home could face new tax obligations simply because they’re following public health guidelines, businesses too could find themselves with unplanned tax exposure. Relief legislation should ensure that businesses do not see any change to their tax situation solely as a result of employees working remotely due to the pandemic.

Companies that operate in multiple states must apportion their income to determine how much tax to pay in each state in which they do business. Some twenty states utilize apportionment formulas that include payroll attributable to the state as a factor for determining business tax obligations.[19] That means that an employee working from one of these twenty states due to COVID-related shutdowns could unwittingly trigger new tax obligations for their employer, if the company didn’t previously have any nexus there. And companies that already have nexus in a state could see their apportionment change significantly, through no planning or fault of their own.

As with the individual income tax side, there is existing legislation that Congress can look to for language when constructing a new bill to head off COVID-related tax problems. The Business Activity Tax Simplification Act (BATSA), introduced by Reps. Steve Chabot (R-OH) and Bobby Scott (D-VA), was introduced prior to the COVID-19 crisis to address the problem of states aggressively asserting the power to tax the business income of companies with tangential connections to the state.[20] The language utilized in the bill could provide a worthy base for any business protections being written into COVID response legislation.

More specifically, Section 2 of BATSA seeks to modernize Public Law 86-272, which limits the ability of states to impose tax on companies that lack significant connection to the state. Adding language to establish that a business will not be considered to have engaged in business activity in the state merely because an employee performed work at home in compliance with public health recommendations would go a long way toward protecting companies from new tax paperwork.

Relief legislation should also explore the option of pre-empting municipalities that try to claim tax income from remote work. As previously mentioned, Ohio has acted proactively to bar municipalities from assessing income taxes on individuals (and businesses) due solely to pandemic-related remote work, but the best way to protect taxpayers would be for this limitation to be standard across all states with local income taxes.[21] Federal pre-emption of local law is less common than pre-emption of state law and should be evaluated with caution, but given the number of municipalities that impose and administer their own income taxes, Congress should consider whether to extend its directive to localities as well.

Current Bills Addressing These Issues

Thankfully, some Members of Congress have recognized the significant damage that could come from aggressive state action targeting COVID-related remote work. Most notably, Senator John Thune (R-SD) announced that he’d be introducing new legislation in a Wall Street Journal op-ed echoing many of the themes NTUF has highlighted on this topic.[22]

Thune’s bill, S. 3995, builds upon the Mobile Workforce Income Tax Simplification Act with some straightforward adjustments.[23] First, for emergency volunteers that worked in another state to aid in COVID-19 response, it establishes a higher threshold of 90 days working in a state before those workers can be subject to its income tax. This should provide sufficient protection for the thousands of doctors, nurses, construction workers, and others that traveled to the hardest-hit areas of the country to provide “surge capacity.”

Next, the bill adds a new section that attributes COVID-related remote work to the employee’s ordinary work location, which will provide certainty and simplicity to millions of Americans.

With regard to business taxation, S. 3995 includes language stating that COVID-related remote work on the part of an employee cannot, on its own, be sufficient to establish taxable nexus for a business. Additionally, it requires that states attribute COVID-related remote work to the ordinary work location for apportionment purposes. Taken together, these changes would simplify tax requirements substantially in the face of the complicating factors of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Notably, the Thune bill does allow employers that maintain a system that tracks employee work locations to elect, at their own discretion, to instead attribute that work to the location where it was actually performed. This in effect allows businesses to choose the system that best suits their particular needs. For example, many large employers regularly track work location for their employees and it might actually prove more difficult to attribute work to the “ordinary” office location than to simply use the data they’re already collecting. With this provision in place, however, they are free to select the approach that is easiest for them.

In addition to Senator Thune’s bill, Representative Scott DesJarlais (R-TN) has introduced legislation that is related to the concerns outlined in this paper. Called the “Prevent Restrictions on Volunteers’ Incomes During Emergencies Act,” or PROVIDE Act, H.R. 6970 would make a state ineligible for federal financial assistance if it imposes tax on the income of a volunteer that has traveled to the state to assist in a federally-declared emergency.[24]

The introduction of the PROVIDE Act is commendable for shining a light on this important problem. That said, it only pertains to one element — taxation of volunteers — of the tax challenges individuals are facing in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, and does not provide any protection or certainty to companies facing business income tax or withholding problems. It also may be overly broad as written.

Conclusion

With relatively simple legislation, Congress could act to protect employees forced to shift to a remote setting and employers who did the right thing by sending their employees home from unscrupulous revenue departments.

American taxpayers have more than enough concerns to occupy themselves with without state revenue officials hassling them over inflexible applications of tax law. Congress should step in to help them with common sense relief legislation for remote work for the period of the pandemic.

[1] Brynjolfsson, Erik et al. “COVID-19 and Remote Work: An Early Look at US Data.” National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27344

[2] Moylan, Andrew and Wilford, Andrew. “Don’t Let COVID Remote Work Become a Tax Trap.” National Taxpayers Union, April 24, 2020, https://www.ntu.org/foundation/detail/dont-let-covid-remote-work-become-a-tax-trap.

[3] Ford, James. “Exclusive: Volunteers Recruited from out-of-State Must Pay NY Taxes.” WPIX, April 10, 2020. https://www.pix11.com/news/coronavirus/exclusive-volunteers-recruited-from-out-of-state-must-pay-ny-taxes.

[4] Alabama Department of Revenue. (2020). “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Updates.” Retrieved from: https://revenue.alabama.gov/coronavirus-covid-19-updates/ (Accessed June 24, 2020.)

[5] District of Columbia Office of Tax and Revenue. (2020). “OTR Tax Notice 2020-05 COVID-19 Emergency Income and Franchise Tax Nexus.” Retrieved from: https://otr.cfo.dc.gov/release/otr-tax-notice-2020-05-covid-19-emergency-income-and-franchise-tax-nexus

[6] Georgia Department of Revenue. (2020). “Coronavirus Tax Relief FAQs.” Retrieved from: https://dor.georgia.gov/coronavirus-tax-relief-faqs (Accessed June 24, 2020)

[7] Indiana Department of Revenue. (2020). “Coronavirus Information: All ‘Helping Hoosiers’ COVID-19 Relief Services.” Retrieved from: https://www.in.gov/dor/7078.htm (Accessed June 24, 2020)

[8] Iowa Department of Revenue. (2020). “IDR Orders & News Releases.” Retrieved from: https://tax.iowa.gov/COVID-19 (Accessed June 24, 2020)

[9] Tax Alert Comptroller of Maryland. (2020). “Employer Withholding Requirements for Teleworking Employees During the Covid-19 Emergency.” Retrieved from: https://www.marylandtaxes.gov/covid/documents/TaxAlert050420-EmployerWithholdingonTeleworkers.pdf

[10] Massachusetts Department of Revenue. (2020). “TIR 20-5: Massachusetts Tax Implications of an Employee Working Remotely due to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Retrieved from: https://www.mass.gov/technical-information-release/tir-20-5-massachusetts-tax-implications-of-an-employee-working

[11] Minnesota Department of Revenue. (2020). “COVID-19 FAQs for Businesses.” Retrieved from: https://www.revenue.state.mn.us/index.php/covid-19-faqs-businesses (Accessed June 24, 2020)

[12] Mississippi Department of Revenue. (2020). “Mississippi Department of Revenue Response to Requests for Relief.” Retrieved from: https://twitter.com/MSDeptofRevenue/status/1243258128713551875/photo/2 (Accessed June 24, 2020)

[13] New Jersey Division of Taxation. (2020). “Telecommuter COVID-19 Employer and Employee FAQ.” Retrieved from: https://www.state.nj.us/treasury/taxation/covid19-payroll.shtml (Accessed June 24, 2020)

[14] North Dakota Office of State tax Commissioner. (2020). “COVID-19 Tax Guidance.” Retrieved from: https://www.nd.gov/tax/covid-19-tax-guidance/ (Accessed June 24, 2020)

[15] “COVID-19 telework triggers state withholding guidance.” Eversheds Sutherland LLP, April 20, 2020. https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/covid-19-telework-triggers-state-tax-61603/

[16] Rhode Island Department of Revenue Division of Taxation. (2020). “Division addresses questions involving nexus and apportionment.” Retrieved from: https://www.tax.ri.gov/Advisory/ADV_2020_24.pdf

[17] State of South Carolina Department of Revenue. (2020). “Nexus and Income Tax Withholding Requirements for Employers with Workers Temporarily Working Remotely as a Result of COVID-19.” SC Information Letter #20-11. Retrieved from: “https://dor.sc.gov/resources-site/lawandpolicy/Advisory%20Opinions/IL20-11.pdf

[18] Rep. Hank Johnson. “H.R.5674 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): Mobile Workforce State Income Tax Simplification Act of 2020.” Congress.gov, February 7, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/5674/text.

[19] Federation of Tax Administrators. (2020). “State Apportionment of Corporate Income.” Retrieved from: https://www.taxadmin.org/assets/docs/Research/Rates/apport.pdf.

[20] Rep. Steve Chabot. “H.R.3063 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): Business Activity Tax Simplification Act of 2019,” Congress.gov, June 28, 2019. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/3063.

[21] Reps. Jena Powell and Derek Merrin. “House Bill 197 | The Ohio Legislature.” Retrieved from: https://www.legislature.ohio.gov/legislation/legislation-summary?id=GA133-HB-197 (Accessed June 24, 2020)

[22] Sen. John Thune. “State Taxes Shouldn’t Be Another Pandemic Worry.” The Wall Street Journal, June 17, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/state-taxes-shouldnt-be-another-pandemic-worry-11592434903

[23] Sen. John Thune, “S.3995 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): A Bill to Limit the Authority of States or Other Taxing Jurisdictions to Tax Certain Income of Employees for Employment Duties Performed in Other States or Taxing Jurisdictions, and for Other Purposes.” Congress.gov, June 18, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/3995.

[24] Rep. Scott DesJarlais, “H.R.6970 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): PROVIDE Act.” Congress.gov, May 22, 2020 https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6970.